.

Condición fitosanitaria: Presente

Grupo de cultivos: Hortícolas y Frutícolas

Especie hospedante: Frutilla, fresa (español), fragola (italiano), morango (portugués), fraise (francés), strawberry (inglés), terdbeere (alemán), (Fragaria × ananassa (Weston) Duchesne)

Rango de hospedantes: no específico / amplio

Epidemiología: policíclica, subaguda

Etiología: Hongo. Necrotrófico

Agente causal: Botrytis cinerea Pers.:Fr. (anamórfo) / Botryotinia fuckeliana (de Bary) Whetzel 1945 (teleomorfo)

Taxonomía: Eukaryota > Fungi > Dikarya > Ascomycota > Pezizomycotina > Leotiomycetes > Helotiales > Sclerotiniaceae > Botrytis

Rango de hospedante: B. cinerea es un hongo polífago con un amplio rango de hospedantes y de amplia difusión mundial, siendo el agente causal de la podredumbre gris en diversos cultivos de importancia económica, tales como el arándano, la vid, el kiwi, la frutilla, el tomate, etc. Se han reportado más de 1400 especies de plantas atacadas por Botrytis, de 596 géneros, en 170 familias (Fillinger & Elad, 2016).

.

- Cuerpos de fructificación sexual (apotecio), a partir de estructura de resistencia (esclerocio), del teleomorfo Botryotinia fuckeliana. Autor: Dean et al., 2012.

.

.

Síntomas

Aparece como manchas castaña claras para luego desarrollar un moho gris. Ataca hojas, los peciolos de las hojas, flores, frutos, yemas, brotes y plántulas , produciendo necrosis. El principal síntoma se observa en los

frutos maduros y corresponde a una pudrición blanda acompañada de una masa de micelio y conidios que le dan el nombre a la enfermedad.

.

- Autor: Ed Sikora

.

Daños

El moho gris (gray mold) causado por Botrytis cinerea es la mayor causa de pérdidas postcosecha en frutilla. El patógeno puede atacar al cultivo en cualquier estado de desarrollo del mismo y puede infectar cualquier parte de la planta, pero el daño se concentra en las flores y frutos.

.

Esquema del ciclo de vida del patógeno

.

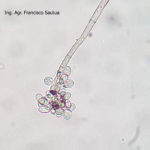

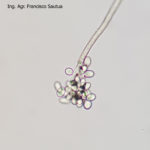

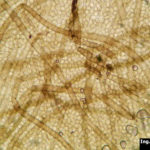

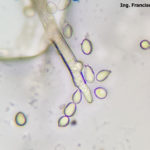

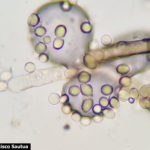

Epidemiología y condiciones predisponentes

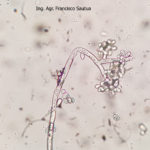

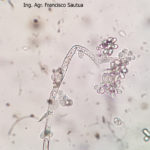

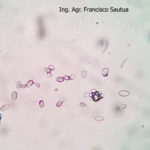

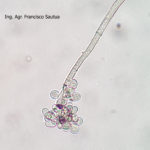

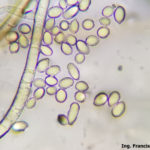

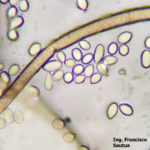

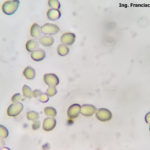

B. cinerea tiene un amplio rango de hospedantes (altamente polífago), puede infectar a cientos o miles de plantas, causando pérdidas importantes en más de 200 cultivos diferentes en todo el mundo. Este hongo continúa creciendo aún a 0°C (32°F), aunque muy lentamente, por lo que durante la poscosecha la presencia de un fruto enfermo puede terminar pudriendo todos los frutos adyacentes. B. cinera produce gran cantidad de micelio gris y varios conidióforos largos y ramificados, cuyas células apicales redondeadas producen racimos de conidios ovoides, unicelulares, incoloros o de color gris. Los conidióforos y los racimos de conidios se asemejan a un racimo de uvas. El hongo libera fácilmente sus conidios cuando el clima es húmedo y luego éstos son diseminados por el viento. El hongo a menudo produce esclerocios irregulares, planos, duros y de color negro. Es un saprófito que sobrevive en restos culturales y como esclerocios en el suelo.

El genoma de B. cinerea ha sido secuenciado, revelando la diversidad potencial en el metabolismo secundario, el cual podría estar involucrado en la adaptación a los nichos ecológicos específicos ( Amselem et al., 2011); y la capacidad de Botrytis para suprimir las defensas del hospedante por varios mecanismos (Hahn et al., 2014).

En general el moho gris (Botryotinia fuckeliana / Botrytis cinerea) se considera un patógeno débil, que solo infecta las plantas dañadas o débiles. El ciclo de la enfermedad se inicia con la germinación de los esclerocios o restos de micelio y conidios que permanecen en residuos infectados de frutilla. El crecimiento vegetativo genera rápidamente conidióforos, que emiten numerosos conidios, los que son diseminados por el viento. La inoculación ocurre en los estigmas de las flores abiertas, pétalos o restos de flores senescentes y frutos. Si las condiciones ambientales son apropiadas (presencia de agua libre y temperaturas mayores a 15 °C), los conidios germinan y el micelio crece dentro de los tejidos, produciendo una pudrición blanda. Luego, el micelio emerge sobre el fruto y genera nuevos conidióforos y conidios, los que seguirán infectando nuevas flores y frutos (enfermedad policíclica). Se disemina por acción de la lluvia, el viento y corrientes de aire bajo las cubiertas plásticas. Los conidios pueden ser transportados a grandes distancias por corrientes de aire. El hongo puede vivir como saprófito en tejidos en descomposición, aumentando aún más el nivel de inóculo en el ambiente. Hacia el final de la estación de crecimiento, el micelio del hongo se agrega en estructuras compactas y de color negro, denominadas esclerocios, las cuales resisten el invierno (estructuras de resistencia).

.

- Autor: Ed Sikora

.

Manejo de la enfermedad

* Plantar variedades resistentes o de mejor comportamiento (si hubiera disponibles en el mercado).

* Eliminación de tejidos viejos, residuos de plantas y frutos infectados (ayuda a disminuir la carga de inóculo inicial).

* Evitar altas densidades de plantaciones para tener buena ventilación y facilitar el secado del follaje después de una lluvia o rocío.

* Lograr una fertilización adecuadas para mantener un balance adecuado de nutrientes, como por ejemplo la relación nitrógeno/calcio: excesos de N producen tejidos más suculentos, lo que facilita el ataque del

hongo y su posterior colonización; mientras que las aplicaciones de calcio mejoran la resistencia de la fruta al ataque de Botrytis.

* Control químico: desde la floración si las condiciones son propicias para el desarrollo del hongo (follaje mojado y temperaturas mayores a 15 °C). Especial atención se debe prestar al uso de buenas prácticas agrícolas para evitar el surgimiento de la resistencia a fungicidas por parte de este patógeno (Hahn, 2014).

* Control biológico: existen productos a base de Trichoderma y Bacillus subtilis, los cuales pueden ser aplicados en primavera. En cultivos ornamentales se ha tenido exito con el uso de levaduras filosféricas (López Ortega, 2012), por lo que investigaciones adicionales en frutilla son necesarias para testear este prometedor agente de control biológico.

* El uso de atmósfera controlada (AC) o atmósfera modificada (AM) debe ser considerado como un complemento a los adecuados procedimientos de manejo de la temperatura y humedad relativa. En ambas implementaciones el principal efecto sobre la fisiología de la fruta es la disminución del metabolismo y por lo tanto el control del hongo. La aplicación de AM en el embalaje con 10 a 15% de CO2 reduce el crecimiento de B. cinerea y la tasa de respiración, extendiendo la vida de poscosecha. El método más común para la aplicación de AM es el uso de una película plástica para cubrir completamente el pallet o carga por caja.

.

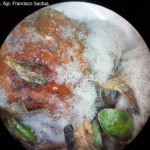

- 1 Moho gris frutilla (Botrytis cinerea)

- 02 Botrytis cinerea creciendo sobre frutilla

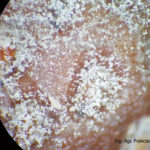

- 03 Botrytis cinerea

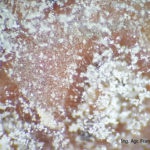

- 04 Botrytis cinerea

- 05 Botrytis cinerea

- 06 Conidios sobre conidióforos libres de Botrytis cinerea

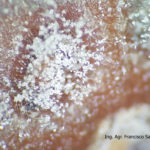

- 07 Conidios sobre conidióforos libres de Botrytis cinerea

- 08 Conidios sobre conidióforos libres de Botrytis cinerea

- 09 Conidios sobre conidióforos libres de Botrytis cinerea

- 10 Conidios sobre conidióforos libres de Botrytis cinerea

- 11 Conidios sobre conidióforos libres de Botrytis cinerea

- 12 Conidios sobre conidióforos libres de Botrytis cinerea

- 13 Conidios sobre conidióforos libres de Botrytis cinerea

- 14 Conidios sobre conidióforos libres de Botrytis cinerea

- 15 Conidios sobre conidióforos libres de Botrytis cinerea

- 16 Conidios sobre conidióforos libres de Botrytis cinerea

- 17 Conidios de Botrytis cinerea

- 18 Conidios sobre conidióforos libres de Botrytis cinerea

- 19 Conidios sobre conidióforos libres de Botrytis cinerea

- 20 Conidios sobre conidióforos libres de Botrytis cinerea

- 21 Conidios sobre conidióforos libres de Botrytis cinerea

- 22 Conidios sobre conidióforos libres de Botrytis cinerea

- 23 Conidios sobre conidióforos libres de Botrytis cinerea

- 01 Frutilla con 100% de incidencia de Botrytis cinerea, a las 24 hs de llegada al mercado central de Bs. As. Zona de producción Coronda, Sta Fe.

- 02 Frutilla con 100% de incidencia de Botrytis cinerea, a las 24 hs de llegada al mercado central de Bs. As. Zona de producción Coronda, Sta Fe.

- 03 Frutilla con 100% de incidencia de Botrytis cinerea, a las 24 hs de llegada al mercado central de Bs. As. Zona de producción Coronda, Sta Fe.

- 01 Conidios de Botrytis cinerea en frutilla

- 02 Conidios de Botrytis cinerea en frutilla

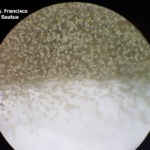

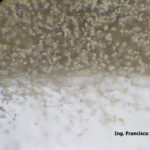

- 03 Cultivo de Botrytis cinerea en APG, aislado a partir de cultivo de frutilla

- 04 Cultivo de Botrytis cinerea en APG, aislado a partir de cultivo de frutilla

- 05 Cultivo de Botrytis cinerea en APG, aislado a partir de cultivo de frutilla

- 06 Cultivo de Botrytis cinerea en APG, aislado a partir de cultivo de frutilla

- 07 Cultivo de Botrytis cinerea en APG, aislado a partir de cultivo de frutilla

- 08 Cultivo de Botrytis cinerea en APG, aislado a partir de cultivo de frutilla

- 09 Cultivo de Botrytis cinerea en APG, aislado a partir de cultivo de frutilla

- 10 Conidios en cultivo de Botrytis cinerea en APG, aislado a partir de cultivo de frutilla

- 11 Conidios y conidióforos de Botrytis cinerea aislado de frutilla.

- 12 Conidios y conidióforos de Botrytis cinerea aislado de frutilla.

- 13 Conidios y conidióforos de Botrytis cinerea aislado de frutilla.

- 14 Conidios de Botrytis cinerea aislado de frutilla.

- 15 Conidios y conidióforos de Botrytis cinerea aislado de frutilla.

- 16 Conidios y conidióforos de Botrytis cinerea aislado de frutilla.

.

.

.

Bibliografía

Botrytis cinerea. Sistema Nacional Argentino de Vigilancia y Monitoreo de plagas

Amiri A, Heath SM, Peres NA (2013) Phenotypic Characterization of Multifungicide Resistance in Botrytis cinerea Isolates from Strawberry Fields in Florida. Plant Disease 97(3): 393-401. doi: 10.1094/PDIS-08-12-0748-RE

Amselem J, Cuomo CA, van Kan JAL, Viaud M, Benito EP, et al. (2011) Genomic Analysis of the Necrotrophic Fungal Pathogens Sclerotinia sclerotiorum and Botrytis cinerea. PLoS Genet 7(8): e1002230. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002230

Bi K, Scalschi L, Jaiswal N, et al. (2021) The Botrytis cinerea Crh1 transglycosylase is a cytoplasmic effector triggering plant cell death and defense response. Nature Communications 12: 2166. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-22436-1

Cai Q, Qiao L, Wang M, He B, Lin FM, Palmquist J, Huang HD, Jin H (2018) Plants send small RNAs in extracellular vesicles to fungal pathogen to silence virulence genes. Science 17 May 2018: eaar4142. DOI: 10.1126/science.aar4142

Cheon W, Kim YS, Balaraju K, et al. (2016) Postharvest Control of Botrytis cinerea and Monilinia fructigena in Apples by Gamma Irradiation Combined with Fumigation. Journal of Food Protection 79(8): 1410-1417. doi: 10.4315/0362-028X.JFP-15-532

Cosseboom SD, Hu M (2021) Identification and Characterization of Fungicide Resistance in Botrytis Populations from Small Fruit Fields in the Mid-Atlantic United States. Plant Dis. doi: 10.1094/PDIS-03-20-0487-RE

Cordova LG, Amiri A, Peres NA (2017) Effectiveness of fungicide treatments following the Strawberry Advisory System for control of Botrytis fruit rot in Florida. Crop Protection 100: 163-167. doi: 10.1016/j.cropro.2017.07.002

Cordova LG, Ellis MA, Wilson LL, Madden LV, Peres NA (2018) Evaluation of the Florida Strawberry Advisory System for Control of Botrytis and Anthracnose Fruit Rots in Ohio. Plant Health Progress. doi: 10.1094/PHP-10-17-0062-RS

Dean R, Van Kan JAL, Pretorius ZA, Hammond-Kosack KE, Di Pietro A, Spanu PD, et al. (2012) The Top 10 fungal pathogens in molecular plant pathology. Molecular Plant Pathology 13: 414–430. doi: 10.1111/j.1364-3703.2011.00783.x

Dowling ME, Hu MJ, Schnabel G (2017) Identification and Characterization of Botrytis fragariae Isolates on Strawberry in the United States. Plant Disease 101(10): 1769-1773. doi: 10.1094/PDIS-03-17-0316-RE

Duan Y, Yang Y, Wang JX, et al. (2018) Simultaneous detection of multiple benzimidazole resistant β-tubulin variants of Botrytis cinerea using loop mediated isothermal amplification. Plant Disease (accepted). doi: 10.1094/PDIS-03-18-0542-RE

Emmanuel CJ, van Kan JA, Shaw MW (2018) Differences in the gene transcription state of Botrytis cinerea between necrotic and symptomless infections of lettuce and Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Pathology doi: 10.1111/ppa.12907

Fan F, Hamada MS, Li N, et al. (2017) Multiple Fungicide Resistance in Botrytis cinerea from Greenhouse Strawberries in Hubei Province, China. Plant Disease 101(4): 601-606. doi: 10.1094/PDIS-09-16-1227-RE

Fernández-Ortuño D, Grabke A, Bryson PK, et al. (2014) Fungicide resistance profiles in Botrytis cinerea from strawberry fields of seven southern U.S. states. Plant Disease 98: 825-833. doi: 10.1094/PDIS-09-13-0970-RE

Fernández-Ortuño D, Grabke A, Li X, Schnabel G (2015) Independent Emergence of Resistance to Seven Chemical Classes of Fungicides in Botrytis cinerea. Phytopathology 105(4): 424-432. doi: 10.1094/PHYTO-06-14-0161-R

Fernández-Ortuño D, Pérez-García A, Chamorro M, et al. (2017) Resistance to the SDHI Fungicides Boscalid, Fluopyram, Fluxapyroxad, and Penthiopyrad in Botrytis cinerea from Commercial Strawberry Fields in Spain. Plant Disease 101(7): 1306-1313. doi: 10.1094/PDIS-01-17-0067-RE

Fillinger S, Elad Y (2016) Botrytis – the Fungus, the Pathogen and its Management in Agricultural Systems. Springer International Publishing Switzerland. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-23371-0

Frías M, González C, Brito N (2011) BcSpl1, a cerato-platanin family protein, contributes to Botrytis cinerea virulence and elicits the hypersensitive response in the host. New Phytologist 192: 483–495. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2011.03802.x

Garfinkel AR (2021) The History of Botrytis Taxonomy, the Rise of Phylogenetics, and Implications for Species Recognition. Phytopathology 111(3): 437-454. doi: 10.1094/PHYTO-06-20-0211-IA

Grabke A, Stammler G (2015) A Botrytis cinerea Population from a Single Strawberry Field in Germany has a Complex Fungicide Resistance Pattern. Plant Dis. 99(8): 1078-1086. doi: 10.1094/PDIS-07-14-0710-RE

Gupta R, Anand G, Pizarro L, et al. (2021) Cytokinin Inhibits Fungal Development and Virulence by Targeting the Cytoskeleton and Cellular Trafficking. ASM Journals mBio 12. doi: 10.1128/mBio.03068-20

Hahn M (2014) The rising threat of fungicide resistance in plant pathogenic fungi: Botrytis as a case study. Journal of Chemical Biology 7: 133–141. doi: 10.1007/s12154-014-0113-1

Hahn M, Viaud M, van Kan J (2014) The Genome of Botrytis cinerea, a Ubiquitous Broad Host Range Necrotroph. In: R. A. Dean et al. (eds.), Genomics of Plant-Associated Fungi and Oomycetes: Dicot Pathogens, Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg 2014. doi: 10.1007/978-3-662-44056-8_2

Hu MJ, Cox KD, Schnabel G (2016) Resistance to Increasing Chemical Classes of Fungicides by Virtue of “Selection by Association” in Botrytis cinerea. Phytopathology 106(12): 1513-1520. doi: 10.1094/PHYTO-04-16-0161-R

Hu MJ, Dowling ME, Schnabel G (2018) Genotypic and Phenotypic Variations in Botrytis spp. Isolates from Single Strawberry Flowers. Plant Disease 102(1): 179-184. doi: 10.1094/PDIS-06-17-0891-RE

Izquierdo-Bueno I, González-Rodríguez VE, Simon A, et al. (2018) Biosynthesis of abscisic acid in fungi: identification of a sesquiterpene cyclase as the key enzyme in Botrytis cinerea. Environ Microbiol. 20(7): 2469-2482. doi: 10.1111/1462-2920.14258

Jiang M, Xu X, Song J, et al. (2021) Streptomyces botrytidirepellens sp. nov., a novel actinomycete with antifungal activity against Botrytis cinerea. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 71(9). doi:

Kirschbaum DS, Alderete GL, Rivadeneira M, et al. (2015) Reconocimiento de plagas, organismos benéficos y enfermedades habituales del cultivo de frutillas en en noroeste argentino. Guía práctica de campo. Editor/es: Min. de Producción, SAF, Delegación Jujuy. INTA. PRODERI.. – Página/s: 20.

Kretschmer M, Leroch M, Mosbach A, et al. (2009) Fungicide-Driven Evolution and Molecular Basis of Multidrug Resistance in Field Populations of the Grey Mould Fungus Botrytis cinerea. PLoS Pathog 5(12): e1000696. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000696

Leisen T, Werner J, Pattar P, et al. (2022) Multiple knockout mutants reveal a high redundancy of phytotoxic compounds contributing to necrotrophic pathogenesis of Botrytis cinerea. PLoS Pathog 18(3): e1010367. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1010367

Leroch M, Plesken C, Weber RW, et al. (2013) Gray mold populations in german strawberry fields are resistant to multiple fungicides and dominated by a novel clade closely related to Botrytis cinerea. Appl Environ Microbiol. 79(1): 159-67. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02655-12

Leroux P, Fritz R, Debieu D, Albertini C, Lanen C, Bach J, Gredt M, Chapeland F (2002) Mechanisms of resistance to fungicides in field strains of Botrytis cinerea. Pest Management Science 58: 876–888. doi: 10.1002/ps.566

Li X, Fernández-Ortuño D, Grabke A, Schnabel G (2014) Resistance to Fludioxonil in Botrytis cinerea Isolates from Blackberry and Strawberry. Phytopathology 104(7): 724-732. doi: 10.1094/PHYTO-11-13-0308-R

Li X, Gao X, Hu S, et al. (2022) Resistance to pydiflumetofen in Botrytis cinerea: risk assessment and detection of point mutations in sdh genes that confer resistance. Pest Manag Sci 78: 1448-1456. doi: 10.1002/ps.6762

Liu Y, Liu JK, Li GH, et al. (2019) A novel Botrytis cinerea-specific gene BcHBF1 enhances virulence of the grey mould fungus via promoting host penetration and invasive hyphal development. Molecular Plant Pathology 20(5): 731-747. doi: 10.1111/mpp.12788

Liu YH, Yuan SK, Hu XR. et al. (2019) Shift of Sensitivity in Botrytis cinerea to Benzimidazole Fungicides in Strawberry Greenhouse Ascribing to the Rising-lowering of E198A Subpopulation and its Visual, On-site Monitoring by Loop-mediated Isothermal Amplification. Scientific Reports 9, 11644. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-48264-4

Liu K, Wen Z, Ma Z, et al. (2022) Biological and molecular characterizations of fluxapyroxad-resistant isolates of Botrytis cinerea. Phytopathol Res 4: 2. doi: 10.1186/s42483-022-00107-3

López Ortega MP (2012) Control Biológico de Botrytis sp. mediante levaduras filosféricas en rosas de corte tipo exportación. Tesis de Maestria, Universidad Nacional de Colombia. 111 pp.

Malandrakis AA, Krasagakis N, Kavroulakis N, et al. (2022) Fungicide resistance frequencies of Botrytis cinerea greenhouse isolates and molecular detection of a novel SDHI resistance mutation. Pesticide Biochemistry and Physiology 183: 105058. doi: 10.1016/j.pestbp.2022.105058

Mbengue M, Navaud O, Peyraud R, Barascud M, Badet T, Vincent R, Barbacci A and Raffaele S (2016) Emerging Trends in Molecular Interactions between Plants and the Broad Host Range Fungal Pathogens Botrytis cinerea and Sclerotinia sclerotiorum. Frontiers in Plant Science 7: 422. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2016.00422

McClellan WD, Hewitt WB (1973) Early Botrytis Rot of Grapes: Time of Infection and Latency of Botrytis cinerea Pers. in Vitis vinifera L. Phytopathology 63:1151-1157. doi: 10.1094/Phyto-63-1151

Müller N, Leroch M, Schumacher J, Zimmer D, Könnel A, Klug K, Leisen T, Scheuring D, Sommer F, Mühlhaus T, Schroda M, Hahn M (2018) Investigations on VELVET regulatory mutants confirm the role of host tissue acidification and secretion of proteins in the pathogenesis of Botrytis cinerea. New Phytol. 219: 1062-1074. doi: 10.1111/nph.15221

, , , (2022) Pervasive fungicide resistance in Botrytis from strawberry in Norway: Identification of the grey mould pathogen and mutations. Plant Pathology 71: 1392– 1403. doi: 10.1111/ppa.13557

Noda J, Brito N, Gonzalez C (2010) The Botrytis cinerea xylanase Xyn11A contributes to virulence with its necrotizing activity, not with its catalytic activity. BMC Plant Biol 10: 38. doi: 10.1186/1471-2229-10-38

Oren-Young L, Llorens E, Bi K, Zhang M, Sharon A (2021) Botrytis cinerea methyl isocitrate lyase mediates oxidative stress tolerance and programmed cell death by modulating cellular succinate levels. Fungal Genetics and Biology 146: 103484. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fgb.2020.103484

Petrasch S, Knapp SJ, van Kan JAL, Blanco‐Ulate B (2019) Grey mould of strawberry, a devastating disease caused by the ubiquitous necrotrophic fungal pathogen Botrytis cinerea. Molecular Plant Pathology, 20: 877-892. doi: 10.1111/mpp.12794

Richards JK, Xiao CL, Jurick WM 2nd (2021) Botrytis spp.: A Contemporary Perspective and Synthesis of Recent Scientific Developments of a Widespread Genus that Threatens Global Food Security. Phytopathology 111(3): 432-436. doi: 10.1094/PHYTO-10-20-0475-IA

Roca-Couso R, Flores-Félix JD, Rivas R (2021) Mechanisms of Action of Microbial Biocontrol Agents against Botrytis cinerea. Journal of Fungi. 7(12): 1045. doi: 10.3390/jof7121045

Rollins JA, Cuomo CA, Dickman MB, Kohn LM (2014) Genomics of Sclerotinia sclerotiorum. In: Dean R, Lichens-Park A, Kole C (eds) Genomics of Plant-Associated Fungi and Oomycetes: Dicot Pathogens. pp. 1-17. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg. doi: 10.1007/978-3-662-44056-8_1

Rossi FR, Krapp AR, Bisaro F, Maiale SJ, Pieckenstain FL, Carrillo N (2017) Reactive oxygen species generated in chloroplasts contribute to tobacco leaf infection by the necrotrophic fungus Botrytis cinerea. Plant Journal (accepted). doi: 10.1111/tpj.13718

Rupp S, Plesken C, Rumsey S, Dowling M, Schnabel G, Weber RWS, Hahn M (2017) Botrytis fragariae, a new species causing gray mold on strawberries, shows high frequencies of specific and efflux-based fungicide resistance. Applied Environmental Microbiology 83: e00269-17. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00269-17

Samaras A, Madesis P, Karaoglanidis GS (2016) Detection of sdhB Gene Mutations in SDHI-Resistant Isolates of Botrytis cinerea Using High Resolution Melting (HRM) Analysis. Front. Microbiol. 7: 1815. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2016.01815

Sautua FJ, Baron C, Pérez-Hernández O, Carmona MA (2019) First report of resistance to carbendazim and procymidone in Botrytis cinerea from strawberry, blueberry and tomato in Argentina. Crop Protection 125: 104879. doi: 10.1016/j.cropro.2019.104879

Shah P, Gutierrez-Sanchez G, Orlando R, Bergmann C (2009) A proteomic study of pectin-degrading enzymes secreted by Botrytis cinerea grown in liquid culture. Proteomics 9: 3126–3135. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200800933

Schouten A, van Baarlen P, van Kan JAL (2008) Phytotoxic Nep1-like proteins from the necrotrophic fungus Botrytis cinerea associate with membranes and the nucleus of plant cells. New Phytologist, 177: 493–505. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2007.02274.x

, (2023) Genetic and molecular landscapes of the generalist phytopathogen Botrytis cinerea. Molecular Plant Pathology 00: 1–19. doi: 10.1111/mpp.13404

Sofianos G, Samaras A, Karaoglanidis G (2023) Multiple and multidrug resistance in Botrytis cinerea: molecular mechanisms of MLR/MDR strains in Greece and effects of co-existence of different resistance mechanisms on fungicide sensitivity. Front. Plant Sci. 14: 1273193. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2023.1273193

ten Have A, Mulder W, Visser J, van Kan JAL (1998) The endopoly- galacturonase gene Bcpg1 is required for full virulence of Botrytis cinerea. Molecular Plant-Microbe Interactions 11(10): 1009–1016. doi: 10.1094/MPMI.1998.11.10.1009

, , , (2023) Plant defensin MtDef4-derived antifungal peptide with multiple modes of action and potential as a bio-inspired fungicide. Molecular Plant Pathology 00: 1– 18. doi: 10.1111/mpp.13336

Tian X, Song L, Wang Y, Jin W, Tong F and Wu F (2018) miR394 Acts as a Negative Regulator of Arabidopsis Resistance to B. cinerea Infection by Targeting LCR. Front. Plant Sci. 9:903. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2018.00903

Tut G, Magan N, Brain P, Xu X (2021) Critical Evaluation of Two Commercial Biocontrol Agents for Their Efficacy against B. cinerea under In Vitro and In Vivo Conditions in Relation to Different Abiotic Factors. Agronomy 11(9):1868. doi: 10.3390/agronomy11091868

Valero-Jiménez CA, Steentjes MBF, Slot JC, Shi-Kunne X, Scholten OE, van Kan JAL (2020) Dynamics in Secondary Metabolite Gene Clusters in Otherwise Highly Syntenic and Stable Genomes in the Fungal Genus Botrytis. Genome Biology and Evolution 12(12): 2491-2507. doi: 10.1093/gbe/evaa218

Van Kan JAL, Stassen JHM, Mosbach A, Van Der Lee TAJ, Faino L, Farmer AD, Papasotiriou DG, Zhou S, Seidl MF, Cottam E, Edel D, Hahn M, Schwartz DC, Dietrich RA, Widdison S, Scalliet G (2017) A gapless genome sequence of the fungus Botrytis cinerea. Molecular Plant Pathology 18: 75–89. doi: 10.1111/mpp.12384

Veloukas T, Karaoglanidis GS (2012) Biological activity of the succinate dehydrogenase inhibitor fluopyram against Botrytis cinerea and fungal baseline sensitivity. Pest. Manag. Sci. 68: 858-864. doi: 10.1002/ps.3241

Weber RWS, Petridis A (2023) Fungicide Resistance in Botrytis spp. and Regional Strategies for Its Management in Northern European Strawberry Production. BioTech 12(4): 64. doi: 10.3390/biotech12040064

Wilkinson SW, Pastor V, Paplauskas S, et al. (2018) Long-lasting β-aminobutyric acid-induced resistance protects tomato fruit against Botrytis cinerea. Plant Pathology 67: 30–41. doi: 10.1111/ppa.12725

Williamson B, Tudzynski B, Tudzynski P, Van Kan JAL (2007) Botrytis cinerea: the cause of grey mould disease. Molecular Plant Pathology 8(5): 561–580. doi: 10.1111/J.1364-3703.2007.00417.X

Wu Y, Saski C, Schnabel G, Xiao S, Hu M (2021) A High-Quality Genome Resource of Botrytis fragariae, a New and Rapidly Spreading Fungal Pathogen Causing Strawberry Gray Mold in the United States. Phytopathology 111(3): 496-499. doi: 10.1094/PHYTO-05-20-0204-IA

Zhang ZQ, Qin GZ, Li BQ, Tian SP (2014) Knocking out Bcsas1 in Botrytis cinerea impacts growth, development, and secretion of extracellular proteins which decreases virulence. Molecular Plant-Microbe Interactions 27: 590–600. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-10-13-0314-R

, , , et al. (2020) Transcriptome analysis and functional validation reveal a novel gene, BcCGF1, that enhances fungal virulence by promoting infection‐related development and host penetration. Molecular Plant Pathology 21: 834– 853. doi: 10.1111/mpp.12934

Artículos:

£31m of strawberries, lettuce goes to waste in the UK. 28 September 2017