.

Condición fitosanitaria: Presente

Grupo de cultivos: Legumbres

Especie hospedante: Garbanzo (Cicer arietinum)

Rango de hospedantes: específico / estrecho. Las especies de Fusarium oxysporum causan marchitamiento en más de 150 hospedantes y varían con formae speciales específicas (Bertoldo et al., 2015; Jangir et al., 2021).

Etiología: Hongo. Necrotrófico

Agente causal: Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. ciceris (Foc)

Taxonomía: Fungi > Ascomycota > Pezizomycotina > Sordariomycetes > Hypocreales > Nectriaceae > Fusarium > Fusarium oxysporum species complex > Fusarium oxysporum

.

Fusarium oxysporum es un hongo «habitante» del suelo, y Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. ciceris (Foc) además puede infectar semilla y transmitirse por semilla (Pande et al., 2007). Por lo tanto, las semillas cosechadas de plantas marchitas cuando se mezclan con semillas sanas pueden llevar el hongo patógeno a nuevas áreas o campos, y pueden establecer la enfermedad en el suelo a niveles de umbral económico dentro de tres campañas agrícolas.

Foc produce dos tipos de esporas asexuales: macroconidios, microconidios y estructuras de resistencia, las clamidosporas. Los macroconidios son rectos a ligeramente curvados, delgados y de paredes delgadas, generalmente con tres o cuatro septos, una célula basal en forma de pie y una célula apical cónica y curva. Generalmente se producen a partir de fialidas sobre conidióforos por división basípeta. Son importantes en la infección secundaria.

Los microconidios son elipsoidales y no tienen tabique o tienen uno solo. Se forman a partir de fialidas en falsas cabezas por división basípeta. Son importantes en la infección secundaria.

Las clamidosporas son globosas y tienen paredes gruesas. Se forman a partir de hifas o, alternativamente, mediante la modificación de células de hifas. Son importantes como órganos de resistencia en suelos donde actúan como inóculos en la infección primaria.

Se desconoce el teleomorfo o etapa reproductiva sexual de F. oxysporum.

Fusarium oxysporum es la especie de Fusarium de mayor importancia económica y más común. Se sabe que este hongo del suelo alberga cepas patógenas (de vegetales, animales y humanos) y no patógenas. Sin embargo, en su concepto actual, F. oxysporum es un complejo de especies que consta de numerosas especies crípticas. La identificación y el nombre de estas especies crípticas se complica por los múltiples sistemas de clasificación subespecíficos y la falta de material vivo de tipo ex que sirva como punto de referencia básico para la inferencia filogenética. Por lo tanto, para avanzar y estabilizar la posición taxonómica de F. oxysporum como especie y permitir el nombramiento de las múltiples especies crípticas reconocidas en este complejo de especies, Lombard et al. (2019) designaron un epitipo para F. oxysporum. Utilizando la inferencia filogenética de múltiples locus y las diferencias morfológicas sutiles con el epitipo recién establecido de F. oxysporum como punto de referencia, pudieron resolver 15 taxones crípticos, descriptas como especies.

A pesar de que las especies de Fusarium tienen un amplio rango de hospedantes, las especies individuales a menudo se asocian con solo una o unas pocas plantas hospedantes (Li et al., 2020). Así por ejemplo, las poblaciones de F. solani patógenas en plantas se han dividido en 12 formae speciales y dos razas (Šišić et al., 2018). Por su parte, en el caso de F. oxysporum f. sp. ciceris se han reportado hasta ocho razas de en todo el mundo (Haware y Nene, 1982; Sharma et al., 2012). Las razas 0, 1A, 1B/C, 5 y 6 se han reportado en Estados Unidos y España, y las razas 1A, 2, 3 y 4 en India. Si bien se han documentado en algunos casos una relación gen por gen para unos pocos genes Foc Avr y genes R del garbanzo, aún no se conoce en forma total la interacción del garbanzo y Foc a nivel molecular (Sharma et al., 2016). La distribución actual de las razas del patógeno no es muy clara debido al gran intercambio de germoplasma y la variabilidad climática (Sharma et al., 2014) y la existencia de múltiples razas en una región. Por lo tanto, para desarrollar estrategias efectivas para el manejo del marchitamiento a través de la resistencia de la planta hospedante, es esencial obtener información sobre la estabilidad de la resistencia de los genotipos en múltiples ambientes.

.

- Cepa patógena de Fusarium oxysporum que causa marchitez en garbanzo. Autor: Keith Weller, USDA-ARS – USDA

.

Antecedentes

El marchitamiento del garbanzo por Fusarium es la principal limitación para la producción de garbanzo en todo el mundo (Sharma et al., 2019).

.

Sintomatología

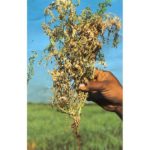

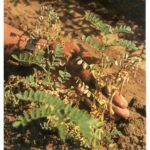

El hongo ingresa a través de las raíces, infectando el sistema vascular de la planta. Este patógeno produce enzimas que degradan las paredes celulares de modo que se forman geles que bloquean el sistema de transporte de la planta. La decoloración de los tejidos internos progresa desde las raíces hasta las partes aéreas de la planta, produciendo un amarillamiento y marchitez del follaje, y finalmente se produce la necrosis. El marchitamiento temprano y el marchitamiento tardío son dos etapas de la incidencia de la enfermedad (Sunkad et al., 2019). Otros síntomas incluyen pecíolos y raquis caídos, amarillamiento y secado de la base hacia arriba de las hojas, pardeamiento en los haces vasculares, marchitamiento y muerte de las plantas.

Es posible identificar las plántulas afectadas aproximadamente tres semanas después de la siembra, ya que muestran síntomas preliminares como hojas caídas y de color pálido. Más tarde colapsan a una posición postrada y se encontrará que tienen tallos encogidos tanto por encima como por debajo del nivel del suelo. Cuando las plantas adultas se ven afectadas, presentan síntomas de marchitamiento que progresan desde los pecíolos y las hojas más jóvenes en dos o tres días hasta la planta completa. Las hojas más viejas desarrollan clorosis mientras que las hojas más jóvenes se mantienen con un verde apagado (menos intenso que lo normal). En una etapa posterior de la enfermedad, todas las hojas se vuelven amarillas. La decoloración de la médula y el xilema se produce en las raíces y se puede ver cuando se cortan longitudinalmente.

El desarrollo de los síntomas del marchitamiento vascular en garbanzo producidos por F. o. f. sp. ciceris depende fuertemente de los grados de tolerancia que presenten las variedades sembradas. Los primeros síntomas de la enfermedad se visualizan al mes de producida la infección pero son más severos en la etapa reproductiva del cultivo (Jiménez Díaz et al., 2015).

- Autor: M.P Haware, Y.L. Nene & S.B. Mathur ICRISAT

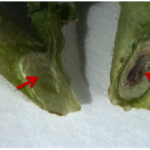

- Decoloración del tallo de una planta de garbanzo infectada artificialmente por Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. ciceris. Planta sana a la izquierda. Autor: Jendoubi et al., 2017.

- Garbanzos afectados por marchitamiento por Fusarium en Beja-Túnez. Autor: Jendoubi et al., 2017.

- M.P Haware, Y.L. Nene & S.B. Mathur ICRISAT

- M.P Haware, Y.L. Nene & S.B. Mathur ICRISAT

- M.P Haware, Y.L. Nene & S.B. Mathur ICRISAT

- M.P Haware, Y.L. Nene & S.B. Mathur ICRISAT

- Screening de genotipos de garbanzo en búsqueda de resistencia a marchitez por Fusarium en parcelas. Autor: Sharma et al., 2019.

.

.

Manejo Integrado

* Siembra de variedades resistentes o tolerantes (cuando estén disponibles)

* Evitar altas densidades de siembra en lotes que hayan presentado la enfermedad.

* Control biológico (Karnwal y Kumar, 2012; Rani y Mane, 2014; Kumari y Khanna, 2014; Bhagat et al. 2014; Karthick et al. 2017; Thaware et al. 2017; Abhiram y Mashi, 2018; Suman and Khanna, 2018; Meshram et al., 2019)

* Activación de defensas naturales (Muthukrishnan et al., 2019)

.

.

Bibliografía

Abhiram P, Mashi H (2018) In vitro antagonism of Trichoderma viridae against Fusarium oxysporum strains. J Pharmacogn Phytochem 7(2): 2816–2819. Link

Agarwal G, Jhanwar S, Priya P, et al. (2012) Comparative Analysis of Kabuli Chickpea Transcriptome with Desi and Wild Chickpea Provides a Rich Resource for Development of Functional Markers. PLoS ONE 7: e52443. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0052443

Ali L, Deokar A, Caballo C, et al. (2015) Fine mapping for double podding gene in chickpea. Theor. Appl. Genet. 129: 77–86. doi: 10.1007/s00122-015-2610-1

Alloosh M, Hamwieh A, Ahmed S, Alkai B (2019) Genetic diversity of Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. ciceris isolates affecting chickpea in Syria. Crop Protection 124: 104863. doi: 10.1016/j.cropro.2019.104863

Altimira F, Godoy S, Arias-Aravena M, et al. (2022) Genomic and Experimental Analysis of the Biostimulant and Antagonistic Properties of Phytopathogens of Bacillus safensis and Bacillus siamensis. Microorganisms 10(4): 670. doi: 10.3390/microorganisms10040670

Ayukawa Y, Asai S, Gan P, et al. (2021) A pair of effectors encoded on a conditionally dispensable chromosome of Fusarium oxysporum suppress host-specific immunity. Commun Biol 4: 707. doi: 10.1038/s42003-021-02245-4

Bartholomew ES, Xu S, Zhang Y, et al. (2022) A chitinase CsChi23 promoter polymorphism underlies cucumber resistance against Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. cucumerinum. New Phytol. doi: 10.1111/nph.18463

Bayraktar H, Dolar FS (2012) Pathogenic variability of Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. ciceris isolates from chickpea in Turkey. Pakistan J. Bot. 44: 821–823.

Bayraktar H, Dolar FS, Maden S (2008) Use of RAPD and ISSR Markers in Detection of Genetic Variation and Population Structure among Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. ciceris Isolates on Chickpea in Turkey. Journal of Phytopathology 156: 146-154. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0434.2007.01319.x

Bhagat D, Sharma P, Sirari A, Kumawat KC (2014) Screening of Mesorhizobium spp. for control of Fusarium wilt in chickpea in vitro conditions. Int J Curr Microbiol Appl Sci 3(4):9 23–930. Link

Bhar A, Jain A, Das S (2021) Soil pathogen, Fusarium oxysporum induced wilt disease in chickpea: a review on its dynamicity and possible control strategies. Proc.Indian Natl. Sci. Acad. 87: 260–274. doi: 10.1007/s43538-021-00030-9

, , , et al (2023) The PTI-suppressing Avr2 effector from Fusarium oxysporum suppresses mono-ubiquitination and plasma membrane dissociation of BIK1. Molecular Plant Pathology 24: 1273–1286. doi: 10.1111/mpp.13369

Bouhadida M, Benjannet R, Madrid E, et al. (2013) Efficiency of marker-assisted selection in detection of ascochyta blight resistance in Tunisian chickpea breeding lines. Phytopathol. Mediterr. 52: 202–211. Link

Bouhadida M, Jendoubi W, Gargouri S, et al. (2017) First report of Fusarium redolens causing Fusarium yellowing and wilt of chickpea in Tunisia. Plant Disease. doi: 10.1094/PDIS-08-16-1114-PDN

Caballo C, Castro P, Gil J, et al. (2019) Candidate genes expression profiling during wilting in chickpea caused by Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. ciceris race 5. PLoS One 14(10): e0224212. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0224212

Castro P, Pistón F, Madrid E, et al. (2010) Development of chickpea near-isogenic lines for Fusarium wilt. Theor. Appl. Genet. 121: 1519–1526. doi: 10.1007/s00122-010-1407-5

Castro P, Rubio J, Millán T, et al. (2012) Fusarium wilt in chickpea: General aspect and molecular breeding. In Fusarium: Epidemiology, Environmental Sources and Prevention. Rios TF, Ortega ER, Eds. Nova Science Publishers: New York, NY, USA, pp. 101–122.

Castro P, Rubio J, Madrid E, et al. (2013) Efficiency of marker-assisted selection for ascochyta blight in chickpea. J. Agric. Sci. 153: 56–67. doi: 10.1017/S0021859613000865

Cobos MJ, Rubio J, Strange RN, et al. (2006) A new QTL for Ascochyta blight resistance in an RIL population derived from an interspecific cross in chickpea. Euphytica 149: 105–111. doi: 10.1007/s10681-005-9058-3

Constantin ME, Fokkens L, de Sain M, et al. (2021) Number of Candidate Effector Genes in Accessory Genomes Differentiates Pathogenic From Endophytic Fusarium oxysporum Strains. Front. Plant Sci. 12: 761740. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2021.761740

Couteaudier Y, Alabouvette C (1990) Survival and inoculum potential of conidia and chlamydospores of Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. lini in soil. Canadian Journal of Microbiology 36: 551-556. doi: 10.1139/m90-096

Dubey SC, Suresh M, Singh B (2007) Evaluation of Trichoderma species against Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. ciceris for integrated management of chickpea wilt. Biol. Control 40: 118–127. doi: 10.1016/j.biocontrol.2006.06.006

El-Sharkawy HHA, Rashad YM, Elazab NT (2022) Synergism between Streptomyces viridosporus HH1 and Rhizophagus irregularis Effectively Induces Defense Responses to Fusarium Wilt of Pea and Improves Plant Growth and Yield. Journal of Fungi 8(7): 683. doi: 10.3390/jof8070683

Flandez-Galvez H, Ford R, Pang ECK, Taylor PWJ (2003) An intraspecific linkage map of the chickpea (Cicer arietinum L.) genome based on sequence tagged microsatellite site and resistance gene analog markers. Theor. Appl. Genet. 106: 1447–1456. doi: 10.1007/s00122-003-1199-y

Fourie G, Steenkamp ET, Gordon TR, Viljoen A (2009) Evolutionary relationships among the Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. cubense vegetative compatibility groups. Appl Environ Microbiol. 75(14): 4770-81. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00370-09

Fravel D, Olivain C, Alabouvette C (2003) Fusarium oxysporum and its biocontrol. New Phytol. 157: 493–502. doi: 10.1046/j.1469-8137.2003.00700.x

Gordon TR (2017) Fusarium oxysporum and the Fusarium Wilt Syndrome. Annu Rev Phytopathol. 55: 23-39. doi: 10.1146/annurev-phyto-080615-095919

Gowda SJM, Radhika P, Kadoo NY, et al. (2009) Molecular mapping of wilt resistance genes in chickpea. Mol. Breed. 24: 177–183. doi: 10.1007/s11032-009-9282-y

Haware MP, Nene YL, Rajeshwari R (1978) Eradication of Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. ciceri transmitted in chickpea seed. Phytopathology 68: 1364–1367. doi: 10.1094/Phyto-68-1364

Haware MP, Nene YL, Pundir RPS, Rao JN (1992) Screening of world chickpea germplasm for resistance to fusarium wilt. F. Crop. Res. 30: 147–154. doi: 10.1016/0378-4290(92)90063-F

Hiremath PJ, Kumar A, Penmetsa RV, et al. (2012) Large-scale development of cost-effective SNP marker assays for diversity assessment and genetic mapping in chickpea and comparative mapping in legumes. Plant Biotechnol. J. 10: 716–732. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7652.2012.00710.x

Imtiaz M, Materne M, Hobson K, et al. (2008) Molecular genetic diversity and linked resistance to ascochyta blight in Australian chickpea breeding materials and their wild relatives. Aust. J. Agric. Res. 59: 554–560. doi: 10.1071/AR07386

Iruela M, Rubio J, Barro F, et al. (2006) Detection of two quantitative trait loci for resistance to ascochyta blight in an intra-specific cross of chickpea (Cicer arietinum L.): Development of SCAR markers associated with resistance. Theor. Appl. Genet. 112: 278–287. doi: 10.1007/s00122-005-0126-9

Irulappan V, Kandpal M, Saini K, et al. (2022) Drought Stress Exacerbates Fungal Colonization and Endodermal Invasion and Dampens Defense Responses to Increase Dry Root Rot in Chickpea. Mol Plant Microbe Interact. 35(7): 583-591. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-07-21-0195-FI

Jain M, Misra G, Patel RK, et al. (2013) A draft genome sequence of the pulse crop chickpea (Cicer arietinum L.). Plant J. 74: 715–729. doi: 10.1111/tpj.12173

Jamil A, Ashraf S (2022) Integrated approach for managing Fusarium wilt of chickpea using Azadirachta indica leaf extract, Trichoderma harzianum and Bavistin. Trop. plant pathol. 47: 727–736. doi: 10.1007/s40858-022-00533-w

Jangir P, Mehra N, Sharma K, et al. (2021) Secreted in Xylem Genes: Drivers of Host Adaptation in Fusarium oxysporum. Front. Plant Sci. 12: 628611. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2021.628611

Jendoubi W, Bouhadida M, Millan T, et al. (2016) Identification of the target region including the Foc0 1 /foc0 1 gene and development of near isogenic lines for resistance to Fusarium Wilt race 0 in chickpea. Euphytica 210: 119–133. doi: 10.1007/s10681-016-1712-4

Jendoubi W, Bouhadida M, Boukteb A, et al. (2017) Fusarium Wilt Affecting Chickpea Crop. Agriculture 7: 23. doi: 10.3390/agriculture7030023

Ji HM, Mao HY, Li SJ, et al. (2021) Fol-milR1, a pathogenicity factor of Fusarium oxysporum, confers tomato wilt disease resistance by impairing host immune responses. New Phytol. 232(2): 705-718. doi: 10.1111/nph.17436

Jiménez-Díaz RM, Trapero-Casas A, de la Colina JC (1989) Races of Fusarium Oxysporum F. Sp. Ciceri Infecting Chickpeas in Southern Spain. In: Tjamos E.C., Beckman C.H. (eds) Vascular Wilt Diseases of Plants. NATO ASI Series (Series H: Cell Biology), vol 28. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-73166-2_39

Jiménez-Gasco M, Pérez-Artés E, Jiménez-Diaz RM (2001) Identification of Pathogenic Races 0, 1B/C, 5, and 6 of Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. ciceris with Random Amplified Polymorphic DNA (RAPD). Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 107: 237–248.

Jiménez-Gasco MDM, Jiménez-Díaz RM (2003) Development of a Specific Polymerase Chain Reaction-Based Assay for the Identification of Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. ciceris and Its Pathogenic Races 0, 1A, 5, and 6. Phytopathology 93: 200–209.

Jiménez-Gasco MM, Navas-Cortés JA, Jiménez-Díaz RM (2004) The Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. ciceris/Cicer arietinum pathosystem: A case study of the evolution of plant-pathogenic fungi into races and pathotypes. Int. Microbiol. 7: 95–104. Link

Jiménez-Díaz RM, Jiménez-Gasco MM (2011) Integrated Management of Fusarium Wilt Diseases. In Control of Fusarium Diseases; Transworld Research Network: Kerala, India. pp. 177–215.

Jiménez-Fernández D, Montes-Borrego M, Jiménez-Díaz RM, et al. (2011) In Planta and Soil Quantification of Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. ciceris and Evaluation of Fusarium Wilt Resistance in Chickpea with a Newly Developed Quantitative Polymerase Chain Reaction Assay. Phytopathology 101: 250–262. doi: 10.1094/PHYTO-07-10-0190

, , , (2013) Quantitative and microscopic assessment of compatible and incompatible interactions between chickpea cultivars and Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. ciceris races. PLoS ONE 8: e61360. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0061360

Jiménez Díaz RM, Castillo P, Jiménez-Gasco M, et al. (2015) Fusarium wilt of chickpeas: Biology, ecology and management. Crop Protection 73: 16-27. doi: 10.1016/j.cropro.2015.02.023

Karnwal A, Kumar V (2012) Influence of plant growth promoting rhizobacteria (PGPR) on the growth of Chickpea (Cicer arietinum L.). Ann Food Sci Technol 13(1): 43–48. Link

Karthick MC, Gopalakrishnan E Rajeshwari, Karthick Pandi V (2017) In vitro eficacy of Bacillus sp. against Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. ciceri causal agent of Fusarium wilt of Chickpea. Int J Curr Microbiol Appl Sci 6(11): 2751–2756. Link

Kumari S, Khanna V (2014) Effect of antagonistic Rhizobacteria co-inoculated with Mesorhizobium ciceris on control of fusarium wilt in chickpea. Afr J Microbiol Res 8(12): 1255–1265. doi: 10.5897/AJMR2013.6481

N (2022) Characterization and biological evaluation of phenazine produced by antagonistic pseudomonads against Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. ciceris. International Journal of Pest Management. doi: 10.1080/09670874.2022.2084176

Landa BB, Navas-Cortés JA, Jiménez-Díaz RM (2004) Integrated management of fusarium wilt of chickpea with sowing date, host resistance, and biological control. Phytopathology 94: 946–960. doi: 10.1094/PHYTO.2004.94.9.946

, , , , (2021) Target of rapamycin controls hyphal growth and pathogenicity through FoTIP4 in Fusarium oxysporum. Molecular Plant Pathology 00, 1– 17. doi: 10.1111/mpp.13108

, , A single gene in Fusarium oxysporum limits host range. Molecular Plant Pathology 22: 108– 116. doi: 10.1111/mpp.13011

, , , Related mobile pathogenicity chromosomes in Fusarium oxysporum determine host range on cucurbits. Molecular Plant Pathology 21: 761– 776. doi: 10.1111/mpp.12927

Lichtenzveig J, Bonfil DJ, Zhang H-B, et al. (2006) Mapping quantitative trait loci in chickpea associated with time to flowering and resistance to Didymella rabiei the causal agent of Ascochyta blight. Theor. Appl. Genet. 113: 1357–1369. doi: 10.1007/s00122-006-0390-3

Lombard L, Sandoval-Denis M, Lamprecht SC, Crous PW (2019) Epitypification of Fusarium oxysporum – clearing the taxonomic chaos. Persoonia 43: 1-47. doi: 10.3767/persoonia.2019.43.01

Madrid E, Chen W, Rajesh PN, et al. (2013) Allele-specific amplification for the detection of ascochyta blight resistance in chickpea. Euphytica 189: 183–190. doi: 10.1007/s10681-012-0753-6

Madrid E, Seoane P, Claros MG, et al. (2014) Genetic and physical mapping of the QTLAR3 controlling blight resistance in chickpea (Cicer arietinum L). Euphytica 198: 69–78. doi: 10.1007/s10681-014-1084-6

, , , et al. (2019) Trichoderma mediate early and enhanced lignifications in chickpea during Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. ciceris infection. J Basic Microbiol. 59: 74– 86. doi: 10.1002/jobm.201800212

Modrzewska M, Bryła M, Kanabus J, Pierzgalski A (2022) Trichoderma as a biostimulator and biocontrol agent against Fusarium in the production of cereal crops: opportunities and possibilities. Plant Pathol. doi: 10.1111/ppa.13578

Mohamed OE, Hamwieh A, Ahmed S, Ahmed NE (2015) Genetic Variability of Fusarium oxysporum f.sp. ciceris Population Affecting Chickpea in the Sudan. Journal of Phytopathology 163: 941-946. doi: 10.1111/jph.12396

Muthukrishnan S, Murugan I, Selvaraj M (2019) Chitosan nanoparticles loaded with thiamine stimulate growth and enhances protection against wilt disease in Chickpea. Carbohydr Polym 212: 169–177. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2019.02.037

, (2023) Constitutive activation of TORC1 signalling attenuates virulence in the cross-kingdom fungal pathogen Fusarium oxysporum. Molecular Plant Pathology 24: 289– 301. doi: 10.1111/mpp.13292

O’Donnell K, Whitaker BK, Laraba I, et al. (2022) DNA Sequence-Based Identification of Fusarium: A Work in Progress. Plant Disease 106(6): 1597-1609. doi: 10.1094/PDIS-09-21-2035-SR

Pande S, Rao JN, Sharma M (2007) Establishment of the Chickpea Wilt Pathogen Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. ciceris in the Soil through Seed Transmission. The Plant Pathology Journal (Korean Society of Plant Pathology) 23: 3–6. doi: 10.5423/PPJ.2007.23.1.003

Postma J, Luttikholt AJG (1993) Benomyl-resistant Fusarium-isolates in ecological studies on the biological control of fusarium wilt in carnation. Netherlands Journal of Plant Pathology 99: 175–188. doi: 10.1007/BF01974662

Rani SR, Mane SS (2014) Effect of different organic amendments on Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. ciceri causing chickpea wilt. Int J Appl Biol Pharm Technol 5(4): 169–170.

Redkar A, Sabale M, Schudoma C, et al. (2022) Conserved secreted effectors contribute to endophytic growth and multi-host plant compatibility in a vascular wilt fungus. Plant Cell.: koac174. doi: 10.1093/plcell/koac174

Sharma KD, Muehlbauer FJ (2007) Fusarium wilt of chickpea: Physiological specialization, genetics of resistance and resistance gene tagging. Euphytica 157: 1–14. doi: 10.1007/s10681-007-9401-y

Sharma M, Babu KT, Gaur PM, et al. (2012) Identification and multi-environment validation of resistance to Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. ciceris in chickpea. Field Crops Research 135: 82–88. doi: 10.1016/j.fcr.2012.07.004

Sharma M, Nagavardhini A, Thudi M, et al. (2014) Development of DArT markers and assessment of diversity in Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. ciceris, wilt pathogen of chickpea (Cicer arietinum L.). BMC Genomics 15: 454. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-15-454

Sharma M, Sengupta A, Ghosh R, et al. (2016) Genome wide transcriptome profiling of Fusarium oxysporum f sp. ciceris conidial germination reveals new insights into infection-related genes. Scientific Reports 6: 37353. doi: 10.1038/srep37353

Sharma M, Ghosh R, Tarafdar A, et al. (2019) Exploring the Genetic Cipher of Chickpea (Cicer arietinum L.) Through Identification and Multi-environment Validation of Resistant Sources Against Fusarium Wilt (Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. ciceris). Frontiers in Sustainable Food Systtems 3: 78. doi: 10.3389/fsufs.2019.00078

Shehabu M, Ahmed S, Sakhuja PK (2008) Pathogenic variability in Ethiopian isolates of Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. ciceris and reaction of chickpea improved varieties to the isolates. Int. J. Pest Manag. 54: 143–149.

Singh C, Vyas D (2021) The Trends in the Evaluation of Fusarium Wilt of Chickpea, Diagnostics of Plant Diseases, Dmitry Kurouski, IntechOpen. doi: 10.5772/intechopen.95612

Šišić A, Baćanović-Šišić J, Al-Hatmi AMS, et al. (2018) The ‘forma specialis’ issue in Fusarium: A case study in Fusarium solani f. sp. pisi. Scientific Reports 8: 1252. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-19779-z

Suman P, Biswas MK (2017) Studies on cultural, morphological and pathogenic variability among the isolates of Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. ciceri causing wilt of chickpea. Int J Plant Animal Environ Sci 7(1): 11–16. Link

Sunkad G, Deepa H, Shruthi TH, et al. (2019) Chickpea wilt: status, diagnostics and management. Indian Phytopathology 72: 619–627. doi: 10.1007/s42360-019-00154-5

Taran B, Warkentin TD, Vandenberg A (2013) Fast track genetic improvement of ascochyta blight resistance and double podding in chickpea by marker-assisted backcrossing. Theor. Appl. Genet. 126: 1639–1647. doi: 10.1007/s00122-013-2080-2

Thaware DS, Kohire OD, Gholve VM (2015) Survey of chickpea wilt (Fusarium oxysporum f.sp. ciceri) disease in Marathwada región of Maharashtra state. Adv Res J Crop Improv 6(2): 134–138.

Thaware DS, Gholve VM, Ghante PH (2017) Screening of chickpea varieties, cultivars and genotypes against Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. ciceri. Int J Curr Microbiol Appl Sci 6(1): 896–904. Link

Thaware DS, Kohire OD, Gholve VM (2017) In vitro efficacy of fungal and bacterial antagonists against Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. ciceri causing chickpea wilt. Int J Curr Microbiol Appl Sci 6(1): 905–909. Link

Varshney RK, Song C, Saxena RK, et al. (2013) Draft genome sequence of chickpea (Cicer arietinum) provides a resource for trait improvement. Nat. Biotechnol. 31: 240–246. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2491

Varshney RK, Mohan SM, Gaur PM, et al. (2014) Marker-Assisted Backcrossing to Introgress Resistance to Fusarium Wilt Race 1 and Ascochyta Blight in C 214, an Elite Cultivar of Chickpea. Plant Genome 7: plantgenome2013.10.0035. doi: 10.3835/plantgenome2013.10.0035

Vicente I, Quaratiello G, Baroncelli R, et al. (2022) Insights on KP4 Killer Toxin-like Proteins of Fusarium Species in Interspecific Interactions. Journal of Fungi. 8(9): 968. doi: 10.3390/jof8090968

Wang L, Calabria J, Chen HW, Somssich M (2022) Overview: The Arabidopsis thaliana – Fusarium oxysporum strain 5176 pathosystem. Journal of Experimental Botany: erac263. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erac263

, , , et al. (2021) FoEG1, a secreted glycoside hydrolase family 12 protein from Fusarium oxysporum, triggers cell death and modulates plant immunity. Molecular Plant Pathology 00: 1– 17. doi: 10.1111/mpp.13041

, , , Current progress on pathogenicity‐related transcription factors in Fusarium oxysporum. Mol Plant Pathol. 00: 1– 14. doi: 10.1111/mpp.13068