.

Condición fitosanitaria: Presente

Grupo de cultivos: Cereales

Especie hospedante: Trigo (Triticum aestivum L., 1753, nom. cons. in [Linnaeus C (1753c)])

Rango de hospedantes: amplio, no específico. El patógeno es capaz de causar Fusariosis de la espiga en trigo (Triticum), la cebada (Hordeum), el arroz (Oryza), la avena (Avena) y la pudrición del tallo y la mazorca por Gibberella en el maíz (Zea). El hongo también puede infectar a otras especies de plantas sin causar síntomas de enfermedad. Otros géneros de hospedantes citados para Gibberella zeae o F. graminearum sensu lato son Agropyron, Agrostis, Bromus, Calamagrostis, Cenchrus, Cortaderia, Cucumis, Echinochloa, Glycine, Hierochloe, Lolium, Lycopersicon, Medicago, Phleum, Poa, Schyrium. Secale, Setaria, Sorghum, Spartina y Trifolium (Goswami y Kistler, 2004).

Epidemiología: monocíclica, subaguda.

Etiología: Hongo. Necrotrófico

Agente causal: Fusarium graminearum Schwabe 1839 (anamorfo); [teleomorfo = Gibberella zeae (Schwein.: Fr.) Petch]

Taxonomía: Eukaryota > Fungi > Dikarya > Ascomycota > Pezizomycotina > Sordariomycetes > Hypocreales > Nectriaceae > Fusarium

.

.

.

Síntomas y signos

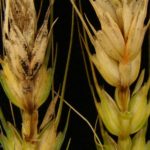

Las espiga o parte de la misma puede quedar blanca y los granos abortados o chuzos. F. graminearum infecta la espiga utilizando las flores como vía de entrada. F. graminearum coloniza los principales componentes de la espiga: partes florales, glumas, granos y raquis. Los primeros síntomas observados son pequeñas áreas pardo-oscuras en la base de las glumas. Cuando la infección de Fusarium ocurre en la base del raquis, toda la espiga puede tornarse blanca. Después de la infección, las aristas se despigmentan y bajo clima cálido y húmedo, se forma una masa rosada de micelio y conidios. Cuando la infección ocurre en el inicio de la floración, habrá una destrucción total del grano en formación. Como la colonización continúa a otras espiguillas a través del raquis, también éstas serán destruidas. Por eso en una espiga infectada, se pueden encontrar granos destruidos en varios estadios de desarrollo. Los granos infectados son arrugados, chuzos, con apariencia áspera y de coloración blanco-rosada por el crecimiento superficial del hongo. Sin embargo, es de destacar que muchos granos a pesar de no tener estos síntomas y signos, pueden estar igualmente infectados por el hongo.

.

- Autor: Stephen Wegulo, University of Nebraska, Lincoln.

- Autor: Stephen Wegulo, University of Nebraska, Lincoln.

- Síntomas de la Fusariosis de la espiga en trigo. La tercera espiguilla de la parte inferior muestra una lesión necrótica oscurecida («sarna») mientras que la segunda y la quinta espiguillas muestran síntomas de blanqueamiento del tejido («tizón»). Autor: Jacki Morrison, USDA ARS Cereal Disease Laboratory; publicado en Goswami y Kistler, 2004

.

Micotoxinas

Los metabolitos secundarios fitotóxicos de los hongos (fitotoxinas fúngicas) son compuestos tóxicos para las plantas producidos por hongos, especialmente por hongos fitopatógenos. Las fitotoxinas fúngicas desempeñan un papel importante en el desarrollo de síntomas de enfermedades de las plantas, como manchas foliares, marchitez, clorosis, necrosis e inhibición y promoción del crecimiento (Xu et al., 2021). F. graminearum cuando infecta trigo sintetiza micotoxinas tales como deoxinivalenol (DON) y nivalenol (NIV) (Ji et al., 2019). El DON es un miembro de la familia de micotoxinas del tricoteceno, que son potentes inhibidores de la síntesis proteica. Esta familia constituye el grupo más grande de micotoxinas de Fusarium, con más de 150 compuestos. La estructura básica es un sistema de anillo tetracíclico y, en función de los sustituyentes, los tricotecenos se agrupan en diferentes tipos (A – D). El DON, también conocido como vomitoxina, es un contaminante común del trigo y de los productos a base de trigo (Bertero et al., 2018). En este segundo grupo se encuentran también la toxina T-2 y el diacetoxiscirpenol. Los granos infectados pueden contener niveles significativos de tricotecenos y micotoxinas estrogénicas, como zearelanona y zearalenol, que son peligrosas para los animales, lo que hace que el grano no sea apto para alimentos o piensos (McMullen et al., 1997). En humanos, F. graminearum se ha relacionado con aleukia tóxica alimentaria y toxicosis Akakabi, enfermedades caracterizadas por náuseas, vómitos, anorexia y convulsiones. La exposición crónica a los tricotecenos (inhibidores de la síntesis de proteínas) tiene efectos de amplio espectro, que incluyen trastornos neurológicos e inmunosupresión (Bennett y Klich, 2003). Aunque se conocen casos de intoxicaciones en humanos, éstas son muchísimo más comunes entre los animales de ganado. El maíz es el principal cereal contaminado, aunque aparece en otros cereales, y en la malta de cervecería.

.

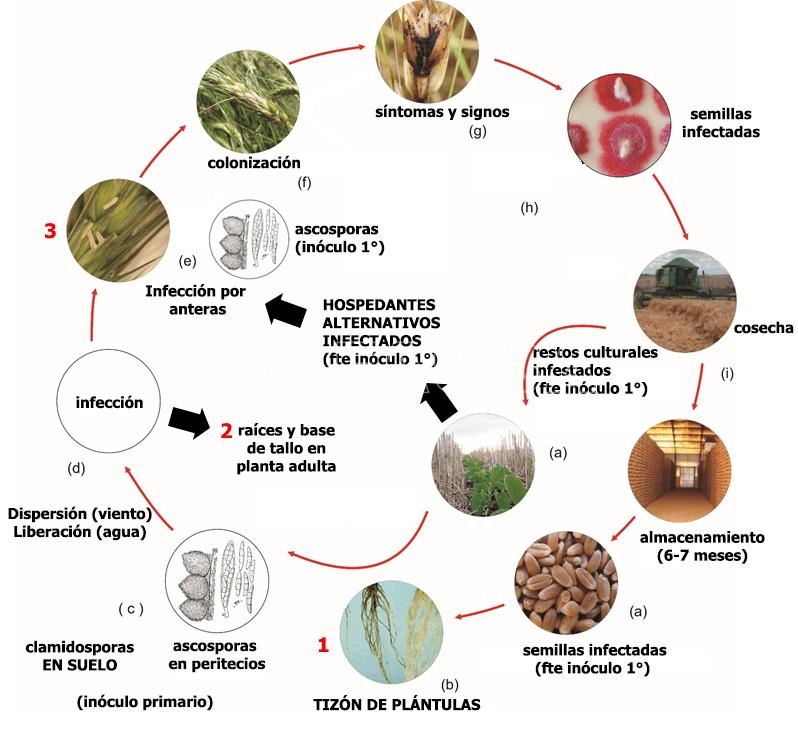

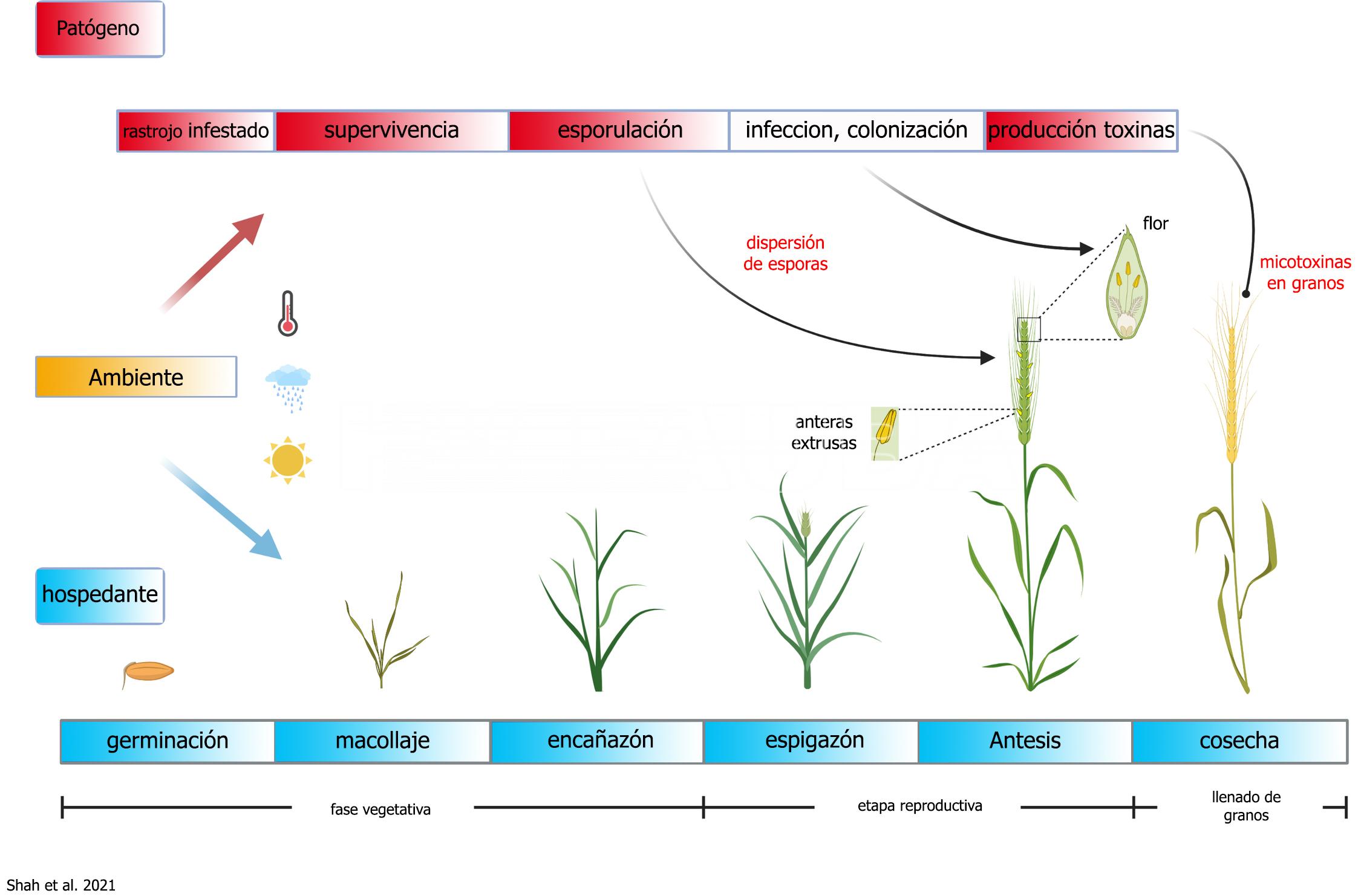

Ciclo de la enfermedad

Las epidemias ocurren esporádicamente en intervalos de varios años. La enfermedad es más frecuente en las regiones de mayor humedad y temperatura durante la floración. El rastrojo infestado de los cultivos de trigo y/o maíz que quedan en la superficie del suelo, y los hospedantes secundarios o malezas (ej: Paspalum (pasto miel), Sorghum halepensis (sorgo de alepo), Digitaria, etc) juegan un papel clave para la supervivencia del hongo en los campos hasta la próxima siembra de cereales de invierno o maíz. Mourelos et al. (2014) identificaron por primera vez en Argentina 54 malezas, pertenecientes a 19 familias botánicas diferentes, incluyendo gramíneas y no gramíneas, como hospedantes alternativos de F. graminearum. Fulcher et al. (2019) sugieren que de acuerdo con los cambios en la patogenicidad relativa de los aislamientos dependiendo de las especies hospedantes, las gramíneas silvestres podrían ejercer una presión selectiva sobre F. graminearum. Lofgren et al. (2017) analizaron 25 especies de gramíneas nativas asintomáticos en E.E. U.U. para detectar la presencia de especies de Fusarium, y confirmaron que son hospedantes asintomáticos utilizando pruebas de re-inoculación. Estos autores demostraron que las especies de Fusarium productoras de micotoxinas prevalecen en gramíneas silvestres filogenéticamente diversas, colonizando múltiples tipos de tejidos, incluyendo semillas, hojas y estructuras de inflorescencia. Las gramíneas inoculadas artificialmente acumularon tricotecenos en mucha menor medida que en el trigo, y las gramíneas infectadas naturalmente mostraron poca o ninguna acumulación.

La liberación de las ascosporas se efectúa al hidratarse los peritecios (estructuras de reproducción sexual del hongo). Este proceso es cíclico, dependiente del agua libre y de la temperatura, y continúa hasta la completa descomposición del rastrojo. Las ascosporas diseminadas por el viento son depositadas sobre las anteras. Una vez inoculadas sobre aquellas, con una humedad relativa superior al 90% y una temperatura de 25-28ºC, las esporas germinan y penetran rápidamente en la flor. Por esta razón, la fusariosis está relacionada con el tiempo lluvioso durante la floración, que es el período de mayor susceptibilidad. Si no hay anteras expuestas el hongo difícilmente llegará al interior de la flor. Después de la penetración del hongo a través del raquis, el progreso de la colonización ocurre solamente con el mojado de la espiga por las precipitaciones, dependiendo de la cantidad de horas de mojado (48 horas) más que del total de precipitaciones. Por lo tanto, dependiendo de las condiciones climáticas (lluvias y temperaturas por arriba de 20-25ºC, es decir, media de 20ºC), F. graminearum puede destruir desde una espiguilla hasta una espiga completa. Las infecciones primarias son las más importantes. El transporte de ascosporas de F. graminearum en la atmósfera puede ser responsable de iniciar la enfermedad a muchos kilómetros de la fuente de inóculo. Por lo tanto, además de la presencia del patógeno a nivel de campo, se debe tener en cuenta el inóculo atmosférico al evaluar el riesgo de la fusariosis (Keller et al., 2014; Karlsson et al., 2021).

.

- Ciclo biológico agronómico de la Fusariosis de la espiga de trigo, causada por Fusarium graminearum. Según el momento de infección se pueden producir 3 enfermedades distintas: (1) tizón de plántulas, (2) espiga blanca o golpe blanco cuando el patógeno infecta raíces y base del tallo en planta adulta, afectando el transporte de agua y nutrientes, y (3) la fusariosis de la espiga cuando se produce la infección floral por anteras a partir de ascosporas. Autor: Erlei Melo Reis

.

Condiciones predisponentes

Precipitaciones frecuentes, alta humedad relativa y temperaturas de alrededor de 25°C durante la floración.

.

Factores de riesgo

* Siembra de cultivares susceptibles

* 48 Horas de mojado y temperatura media de 20ºC durante antesis.

.

- Ciclo de la fusariosis del trigo. Autor: Shah et al. 2021

.

Daños

Importancia relativa moderada a alta. Infecciones medias a severas en el área centro norte de la región triguera pampeana, se informaron en los años 1927, 1945, 1950, 1960, 1963, 1967, 1977, 1978, 1985 y 1993 (Carranza et al., 2008). Los daños más frecuentes están asociados con la menor producción y desarrollo de los granos que oscilan entre el 5 al 30%, y con la producción de toxinas nocivas para animales y humanos.

.

- Autor: Trey Price

- Autor: Trey Price

- Autor: Trey Price

.

Manejo de la Fusariosis

* Uso de variedades resistentes: la mayoría de los cultivares de trigo son susceptibles aunque existen algunos genotipos que han demostrado buen comportamiento (Bai et al., 2018; Yi et al., 2018; Haile et al., 2019; Su et al., 2019; Buerstmayr et al., 2020; Shi et al., 2020). Hasta la fecha, se han identificado más de 50 loci de rasgos cuantitativos únicos (QTL) en diversas poblaciones de trigo. El QTL «Fhb1», descubierto en germoplasma Chino, muestra el nivel más alto, consistente y estable de resistencia en diferentes entornos genéticos. A pesar de los esfuerzos mundiales para incorporar Fhb1 a través del mejoramiento de trigo, solo unos pocos cultivares utilizados actualmente en la producción comercial poseen Fhb1. Se requieren esfuerzos adicionales en investigación y desarrollo para lograr variedades de trigo con niveles de resistencia adecuados. La resistencia del trigo a la fusariosis se clasifica en cinco tipos: resistencia a la infección inicial (tipo I), resistencia a la diseminación (tipo II), resistencia a la acumulación de DON (tipo III), resistencia a la infección del grano (tipo IV) y tolerancia (tipo V) (Mesterházy et al., 1999).

* Diversificar época de siembra: permitiría evitar la concentración de la floración (mayor susceptibilidad) en una misma época.

* Mahmoud (2016) obtuvo resultados promisorios de control biológico, usando Trichoderma harzianum y Bacillus subtilis como agentes de biocontrol.

* Predicción y Aplicación de fungicidas: los órganos a proteger deben ser las anteras expuestas y las presas, que son los órganos susceptibles a la infección. Consecuentemente el período de predisposición del trigo se extiende desde la expulsión de las primeras anteras hasta cerca de la madurez. El fungicida se deber aplicar en plena floración de modo de proteger al mayor número de anteras presas y expuestas. Es probable que las anteras presas cumplan un papel aún más importante en la infección.

En relación a los fungicidas a utilizar, las experiencias nacionales e internacionales muestran que el tebuconazole es eficiente para el control.

Rotación de cultivos: a pesar de ser un hongo necrotrófico, la rotación de cultivos no parece ser una medida eficaz dado que el hongo puede vivir por largos períodos por ser un hongo del suelo, parasitar otras plantas y diseminarse fácilmente por el viento a largas distancias (ascosporas livianas). La Fusariosis de la espiga del trigo es una de las enfermedades de más difícil control.

.

En los últimos años en Argentina, se validó un modelo de predicción con datos de ataque de Fusarium en localidades del Norte de Bs. As. y Sur de Sta. Fe (Moschini, et al, 1997). En este trabajo se aconseja que a partir del período sensible (primeras espigas emergidas) se cuantifiquen las variables meteorológicas NP2 (Número de períodos de dos días, de los cuales el primero registra lluvia y HR superior al 81 %) y el segundo una HR igual o superior al 78%) y DG930 (diariamente y a lo largo del período se acumula lo que excede de 30 C º en temperatura máxima y el residual inferior a 9ºC en temperatura mínima hasta el día 7 (se supone que es la mayor exposición de anteras) alrededor del cual se debería tomar la decisión de la aplicación del fungicida. La duración de ese lapso (FIM, fase inicial de monitoreo) se ajustará en función del cultivar sembrado, y las condiciones meteorológicas del año. Si la FIM es favorable para la enfermedad, se podrá tener un elemento más de juicio al decidir una protección química.

El modelo se basa en: Incidencia (%)= 20,37 +8,63 NP2 – 0.49 DG930

Con este análisis se pretende remarcar la influencia que ejerce la FIM como determinante parcial de la intensidad de la fusariosis.

Se puede acceder al modelo del INTA Clima y Agua desde aquí.

.

- Campo de trigo afectado por la Fusariosis de la espiga del trigo, causada por Fusarium graminearum. Autor: Dirceu Gassen

- Campo de trigo afectado por la Fusariosis de la espiga del trigo, causada por Fusarium graminearum. Autor: Dirceu Gassen

- Autor: Dirceu Gassen

- Autor: Dirceu Gassen

- Autor: Dirceu Gassen

- Autor: Dirceu Gassen

- Autor: Dirceu Gassen

- Autor: Dirceu Gassen

- Autor: Dirceu Gassen

- Autor: Dirceu Gassen

- Autor: Dirceu Gassen

- Autor: Dirceu Gassen

- Autor: Dirceu Gassen

- Autor: Dirceu Gassen

- Autor: Dirceu Gassen

- Autor: Dirceu Gassen

- Autor: Dirceu Gassen

- Autor: Dirceu Gassen

.

Bibliografía

Ricardo Moschini. FUSARIOSIS DE LA ESPIGA DE TRIGO. INTA CLIMA y AGUA

Mapas del grado de riesgo de la FET. Ricardo Moschini. INTA CLIMA y AGUA

An Overview of Fusarium Head Blight. Crop Protection Network. doi: 10.31274/cpn-20211109-0

Alisaac E, Behmann J, Kuska MT, et al. (2018) Hyperspectral quantification of wheat resistance to Fusarium head blight: comparison of two Fusarium species. European Journal of Plant Pathology. doi: 10.1007/s10658-018-1505-9

Alukumbura AS, Bigi A, Sarrocco S, et al. (2022) Minimal impacts on the wheat microbiome when Trichoderma gamsii T6085 is applied as a biocontrol agent to manage Fusarium head blight disease. Front. Microbiol. 13: 972016. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2022.972016

Andersen KF, Morris L, Derksen RC, et al. (2014) Rainfastness of prothioconazole + tebuconazole for Fusarium head blight and deoxynivalenol management in soft red winter wheat. Plant Disease 98: 1398-1406. doi: 10.1094/PDIS-01-14-0092-RE

Andersen KF, Madden LV, Paul PA (2015) Fusarium head blight development and deoxynivalenol accumulation in wheat as influenced by post-anthesis moisture patterns. Phytopathology 105: 210-219. doi: 10.1094/PHYTO-04-14-0104-R

Anderson NR, Freije AN, Bergstrom GC, et al. (2020) Sensitivity of Fusarium graminearum to Metconazole and Tebuconazole Fungicides Before and After Widespread Use in Wheat in the United States. Plant Health Progress 21: 85-90. doi: 10.1094/PHP-11-19-0083-RS

Ashiq S, Edwards SG, Fatukasi O, et al. (2021) In vitro activity of isothiocyanates against Fusarium graminearum. Plant Pathology 00, 1– 8. doi: 10.1111/ppa.13505

Bai G, Su Z, Cai J (2018) Wheat resistance to Fusarium head blight. Canadian Journal of Plant Pathology 40: 336-346. doi: 10.1080/07060661.2018.1476411

Bakker MG, Brown DW, Kelly AC, et al. (2018) Fusarium mycotoxins: a trans-disciplinary overview. Canadian Journal of Plant Pathology 40(2): 161-171. doi: 10.1080/07060661.2018.1433720

Balducci E, Tini F, Beccari G, et al. (2022) A Two-Year Field Experiment for the Integrated Management of Bread and Durum Wheat Fungal Diseases and of Deoxynivalenol Accumulation in the Grain in Central Italy. Agronomy 12(4): 840. doi: 10.3390/agronomy12040840

Barro JP, Flávio MS, Franklin JM, et al. (2020) Are Dmi+qoi Premixes Applied During Flowering Worth for Protecting Wheat Yields from Fusarium Head Blight? A Meta-analysis. OSF Preprints. September 30. doi: 10.31219/osf.io/svzwy

Barro JP, Santana FM, Tibola CS, et al. (2023) Comparison of single- or multi-active ingredient fungicides in a three-spray program for Fusarium head blight and deoxynivalenol control in Brazilian wheat. Crop Protection 174: 106402doi: 10.31219/osf.io/muh6p

Barros G, Zanon MS, Abod A, et al. (2012) Natural deoxynivalenol occurrence and genotype and chemotype determination of a field population of the Fusarium graminearum complex associated with soybean in Argentina. Food Addit Contam Part A Chem Anal Control Expo Risk Assess. 29(2): 293-303. doi: 10.1080/19440049.2011.578588

Barros GG, Zanon MSA, Chiotta ML, et al. (2014) Pathogenicity of phylogenetic species in the Fusarium graminearum complex on soybean seedlings in Argentina. Eur J Plant Pathol 138: 215–222. doi: 10.1007/s10658-013-0332-2

Belizán MME, Gomez AA, Terán Baptista ZP, et al. (2019) Influence of water activity and temperature on growth and production of trichothecenes by Fusarium graminearum sensu stricto and related species in maize grains. International Journal of Food Microbiology 305: 108242. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2019.108242

Bennett JW, Klich M (2003) Mycotoxins. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 16, 497–516. doi: 10.1128/CMR.16.3.497-516.2003

Beres B, Brûlé-Babel A, Ye Z, et al. (2018) Exploring Genotype x Environment x Management synergies to manage fusarium head blight in wheat. Can. J. Plant Pathol. 40: 179-188. doi: 10.1080/07060661.2018.1445661

Bertero A, Moretti A, Spicer LJ, Caloni F (2018 ) Fusarium Molds and Mycotoxins: Potential Species-Specific Effects. Toxins (Basel) 10(6): 244. doi: 10.3390/toxins10060244

, , , , , Mechanism of validamycin A inhibiting DON biosynthesis and synergizing with DMI fungicides against Fusarium graminearum. Mol Plant Pathol. 22: 769– 785. doi: 10.1111/mpp.13060

Bilibio dos Santos G, de OliveiraCoelho MA, Del Ponte EM (2022) Critical-point yield loss models based on incidence and severity of wheat headblast epidemics in the Brazilian Cerrado. OSF Preprints. August 9. doi: 10.31219/osf.io/kqdmx

Birr T, Hasler M, Verreet J-A, Klink H (2020) Composition and Predominance of Fusarium Species Causing Fusarium Head Blight in Winter Wheat Grain Depending on Cultivar Susceptibility and Meteorological Factors. Microorganisms 8(4): 617. doi: 10.3390/microorganisms8040617

Biselli C, Bagnaresi P, Faccioli P, Hu X, Balcerzak M, Mattera MG, Yan Z, Ouellet T, Cattivelli L and Valè G (2018) Comparative Transcriptome Profiles of Near-Isogenic Hexaploid Wheat Lines Differing for Effective Alleles at the 2DL FHB Resistance QTL. Frontiers in Plant Science 9:37. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2018.00037

Bissonnette K, Kolb FL, Ames KA, Bradley C (2018) Effect of Fusarium head blight management practices on mycotoxin contamination of wheat straw. Plant Disease (in press). doi: 10.1094/PDIS-09-17-1385-RE

Brar GS, Karunakaran C, Bond T, et al. (2019) Showcasing the application of synchrotron-based X-ray computed tomography in host-pathogen interactions: the role of the wheat rachilla and rachis nodes in Type-II resistance to Fusarium graminearum. Plant, Cell and Environment. 42: 509-526. doi: 10.1111/pce.13431

Brauer EK, Subramaniam R, Harris LJ (2020) Regulation and Dynamics of Gene Expression During the Life Cycle of Fusarium graminearum. Phytopathology 110(8): 1368-1374. doi: 10.1094/PHYTO-03-20-0080-IA

Brown NA, Evans J, Mead A, Hammond-Kosack KE (2017) A spatial temporal analysis of the Fusarium graminearum transcriptome during symptomless and symptomatic wheat infection. Molecular Plant Pathology 18: 1295–1312. doi: 10.1111/mpp.12564

, , (2020) Breeding for Fusarium head blight resistance in wheat—Progress and challenges. Plant Breed. 139: 429– 454. https://doi.org/10.1111/pbr.12797

Cantoro R, Palazzini JM, Yerkovich N, et al. (2021) Bacillus velezensis RC 218 as a biocontrol agent against Fusarium graminearum: effect on penetration, growth and TRI5 expression in wheat spikes. BioControl 66: 259–270. doi: 10.1007/s10526-020-10062-7

Carmona MA, Pioli R, Reis EM (1999) Malezas hospedantes de hongos necrotroficos causantes de enfermedades en trigo y cebada cervecera en la región pampeana. [Survey of weed plants hosts of pathogenic necrotrophic fungi that cause diseases on wheat and barley in the Argentine Pampas Regions] Rev. Fac. Agron. (B. Aires), 19, pp. 105-110.

Carranza MarceloM, Lori G, Sisterna M (2008) Wheat fusarium head blight 2001 epidemic in the southern Argentinian pampas. Summa Phytopathologica 34(1): 93-94. doi: 10.1590/S0100-54052008000100022

Cavinder B, Sikhakolli U, Fellows KM, Trail F (2012) Sexual development and ascospore discharge in Fusarium graminearum. J Vis Exp. (61): 3895. doi: 10.3791/3895

Cendoya E, Nichea MJ, Monge MP, et al. (2021) Effect of fungicides commonly used for Fusarium head blight management on growth and fumonisin production by Fusarium proliferatum. Revista Argentina de Microbiología. 53: 64–74. doi: 10.1016/j.ram.2019.12.005

Chapman NH, Burt C, Nicholson P (2009) The identification of candidate genes associated with Pch2 eyespot resistance in wheat using cDNA-AFLP. Theor Appl Genet 118: 1045–1057. doi: 10.1007/s00122-009-0961-1

Chen Y, Gao Q, Huang M, et al. (2015) Characterization of RNA silencing components in the plant pathogenic fungus Fusarium graminearum. Nature Scientific Reports 5, Article number: 12500. doi: 10.1038/srep12500

Chen Y, Wang J, Yang N, et al. (2018) Wheat microbiome bacteria can reduce virulence of a plant pathogenic fungus by altering histone acetylation. Nature Communications 9, Article number: 3429. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-05683-7

Chhabra B, Livesay J, Thrasu S, et al. (2024) Testing the Efficacy of a Newly Released Fungicide, Sphaerex, for Control of Fusarium Head Blight in Wheat. Plant Health Progress 25: 427-431. doi: 10.1094/PHP-10-23-0091-RS

Chiotta ML, Alaniz Zanon MS, Palazzini JM, et al. (2021) Fusarium graminearum species complex occurrence on soybean and F. graminearum sensu stricto inoculum maintenance on residues in soybean-wheat rotation under field conditions. Journal of Applied Microbiology 130(1): 208–216. doi: 10.1111/jam.14765

Crippin T, Renaud JB, Sumarah MW, Miller JD (2019) Comparing genotype and chemotype of Fusarium graminearum from cereals in Ontario, Canada. PLoS ONE 14(5): e0216735. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0216735

Cromey M, Parkes R, Sinclair K, Lauren D, Butler R (2002) Effects of fungicides applied at anthesis on Fusarium head blight and mycotoxins in wheat. New Zealand Plant Protection 55: 341-346. doi: 10.30843/nzpp.2002.55.3903

Crous et al. (2022) Fusarium and allied fusarioid taxa (FUSA). Fungal Systematics and Evolution. doi: 10.3114/fuse.2022.09.08

Cuomo CA, Güldener U, Xu JR, et al. (2007) The Fusarium graminearum genome reveals a link between localized polymorphism and pathogen specialization. Science 317(5843): 1400-1402. doi: 10.1126/science.1143708

D’Angelo DL, Bradley CA, Ames KA, Willyerd KT, Madden LV, Paul PA (2014) Efficacy of fungicide applications during and after anthesis against Fusarium head blight and deoxynivalenol in soft red winter wheat. Plant Disease 98: 1387-1397. doi: 10.1094/PDIS-01-14-0091-RE

de Arruda MHM, Zchosnki FL, Silva YK, et al. Genetic diversity of Fusarium meridionale, F. austroamericanum, and F. graminearum isolates associated with Fusarium head blight of wheat in Brazil. Tropical plant pathology 46: 98–108 (2021). doi: 10.1007/s40858-020-00403-3

Del Ponte EM, Spolti P, Ward TJ, et al. (2015) Regional and field-specific factors affect the composition of fusarium head blight pathogens in subtropical no-till wheat agroecosystem of Brazil. Phytopathology 105(2): 246-54. doi: 10.1094/PHYTO-04-14-0102-R

Del Ponte EM, Moreira GM, Ward TJ, et al. (2022) Fusarium graminearum Species Complex: A Bibliographic Analysis and Web-Accessible Database for Global Mapping of Species and Trichothecene Toxin Chemotypes. Phytopathology 112(4): 741-751. doi: 10.1094/PHYTO-06-21-0277-RVW

A (2021) Building on a foundation: advances in epidemiology, resistance breeding, and forecasting research for reducing the impact of Fusarium head blight in wheat and barley. Canadian Journal of Plant Pathology. doi: 10.1080/07060661.2020.1861102

Ding S, Mehrabi R, Koten C, et al. (2009) Transducin Beta-Like Gene FTL1 Is Essential for Pathogenesis in Fusarium graminearum. Eukaryotic Cell 8(6): 867-876. doi: 10.1128/EC.00048-09

Dinolfo MI, Castañares E, StengleIn SA (2017) Fusarium–Plant Interaction: State of the Art – a Review. Plant Protection Science 53(2): 61-70. doi: 10.17221/182/2015-PPS

Dhokane D, Karre S, Kushalappa AC, McCartney C (2016) Integrated Metabolo-Transcriptomics Reveals Fusarium Head Blight Candidate Resistance Genes in Wheat QTL-Fhb2. PLoS One 11(5): e0155851. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0155851

, , , et al. (2020) Gramineous weeds near paddy fields are alternative hosts for the Fusarium graminearum species complex that causes fusarium head blight in rice. Plant Pathology 69: 433– 441. doi: 10.1111/ppa.13143

Doshi P, Šerá B(2023) Role of Non-Thermal Plasma in Fusarium Inactivation and Mycotoxin Decontamination. Plants 12(3): 627. doi: 10.3390/plants12030627

Duffeck MR, Bandara AY, Weerasooriya DK, et al. (2021) Fusarium head blight of small grains in Pennsylvania: unravelling species diversity, toxin types, growth and triazole sensitivity. Phytopathology. doi: 10.1094/PHYTO-02-21-0070-R

Dweba CC, Figlan S, Shimelis HA, et al. (2017) Fusarium head blight of wheat: Pathogenesis and control strategies. Crop Protection 91: 114-122. doi: 10.1016/j.cropro.2016.10.002

Engle JS, Lipps PE, Graham TL, Boehm MJ (2004) Effects of Choline, Betaine, and Wheat Floral Extracts on Growth of Fusarium graminearum. Plant Disease 88(2): 175-180. doi: 10.1094/PDIS.2004.88.2.175

Eranthodi A, González-Peña Fundora D, Montenegro Alonso AP, et al. (2022) Cerato-platanin protein 1 is not critical for Fusarium graminearum growth and aggressiveness, but its overexpression provides an edge to Fusarium head blight in wheat. Canadian Journal of Plant Pathology. doi: 10.1080/07060661.2022.2044910

Etzerodt T, Gislum R, Laursen BB, et al. (2016) Correlation of Deoxynivalenol Accumulation in Fusarium-Infected Winter and Spring Wheat Cultivars with Secondary Metabolites at Different Growth Stages. Journal of Agricultural Food Chemistry 64(22): 4545–4555. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.6b01162

Fabre F, Bormann J, Urbach S, et al. (2019) Unbalanced Roles of Fungal Aggressiveness and Host Cultivars in the Establishment of the Fusarium Head Blight in Bread Wheat. Front. Microbiol. 10: 2857. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2019.02857

Ferrigo D, Raiola A, Causin R (2016) Fusarium Toxins in Cereals: Occurrence, Legislation, Factors Promoting the Appearance and Their Management. Molecules 21(5): 627. doi: 10.3390/molecules21050627

GC (2019) Variable interactions between non-cereal grasses and Fusarium graminearum. Canadian Journal of Plant Pathology 41: 450-456. doi: 10.1080/07060661.2019.1605540

Fumero MV, Yue W, Chiotta ML, et al. (2021) Divergence and gene flow between Fusarium subglutinans and F. temperatum isolated from maize in Argentina. Phytopathology 111(1): 170-183. doi: 10.1094/PHYTO-09-20-0434-FI

Ghimire B, Sapkota S, Bahri BA, et al. (2020) Fusarium head blight and rust diseases in soft red winter wheat in the Southeast United States: state of the art, challenges, and future perspective for breeding. Front. Plant Sci. 11: 1080. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2020.01080

Giroux M-E, Bourgeois G, Dion Y, et al. (2016) Evaluation of Forecasting Models for Fusarium Head Blight of Wheat Under Growing Conditions of Quebec, Canada. Plant Disease 100(6): 1192-1201. doi: 10.1094/PDIS-04-15-0404-RE

Goddard R, Steed A, Scheeren PL, et al. (2021) Identification of Fusarium head blight resistance loci in two Brazilian wheat mapping populations. PLoS ONE 16(3): e0248184. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0248184

González-Domínguez E, Meriggi P, Ruggeri M, Rossi V (2021) Efficacy of Fungicides against Fusarium Head Blight Depends on the Timing Relative to Infection Rather than on Wheat Growth Stage. Agronomy 11(8): 1549. doi: 10.3390/agronomy11081549

Goswami RS, Kistler HC (2004) Heading for disaster: Fusarium graminearum on cereal crops. Mol Plant Pathol. 5(6): 515-525. doi: 10.1111/j.1364-3703.2004.00252.x

Gräfenhan T, Johnston PR, Vaughan MM, et al. (2016) Fusarium praegraminearum sp. nov., a novel nivalenol mycotoxin-producing pathogen from New Zealand can induce head blight on wheat. Mycologia 108(6): 1229-1239. doi: 10.3852/16-110

Ha X, Koopmann B, von Tiedemann A (2016) Wheat blast and Fusarium head blight display contrasting interaction patterns on ears of wheat genotypes differing in resistance. Phytopathology 106: 270-281. doi: 10.1094/PHYTO-09-15-0202-R

Hadjout S, Chéreau S, Atanasova-Pénichon V, et al. (2017) Phenotypic and biochemical characterization of new advanced durum wheat breeding lines from algeria that show resistance to fusarium head blight and to mycotoxin accumulation. Journal of Plant Pathology 99(3). doi: 10.4454/jpp.v99i3.3954

Hagerty CH, Irvine T, Rivedal HM, et al. (2021) Diagnostic Guide: Fusarium Crown Rot of Winter Wheat. Plant Health Progress 22: 176-181. doi: 10.1094/PHP-10-20-0091-DG

Hagerty CH, McLaughlin KR, Kroese DR, Lutcher LK (2021) Phosphorus Supply Does Not Affect Fusarium Crown Rot of Winter Wheat. PhytoFrontiers™ 1:4, 354-358. doi: 10.1094/PHYTOFR-01-21-0010-R

Hagerty CH, Namdar GF, Rivedal HM, et al. (2023) Diagnostic Guide: Fusarium Head Blight of Cereal Grains. Plant Health Progress. doi: 10.1094/PHP-10-22-0110-DG

Haile JK, N’Diaye A, Walkowiak S, et al. (2019) Fusarium Head Blight in Durum Wheat: Recent Status, Breeding Directions, and Future Research Prospects. Phytopathology. 109(10):1664-1675. doi: 10.1094/PHYTO-03-19-0095-RVW

Hales B, Steed A, Giovannelli V, et al. (2020) Type II Fusarium head blight susceptibility conferred by a region on wheat chromosome 4D. Journal of Experimental Botany 71: 4703–4714. doi: 10.1093/jxb/eraa226

Hao JJ, Xie SN, Sun J, et al. (2017) Analysis of Fusarium graminearum Species Complex from Wheat–Maize Rotation Regions in Henan (China). Plant Disease 101(5): 720-725. doi: 10.1094/PDIS-06-16-0912-RE

Hao G, McCormick S, Usgaard T, et al. (2020) Characterization of Three Fusarium graminearum Effectors and Their Roles During Fusarium Head Blight. Frontiers in Plant Science 11: 579553. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2020.579553

Hao G, Naumann TA, Chen H, et al. (2023) Fusarium graminearum Effector FgNls1 Targets Plant Nuclei to Induce Wheat Head Blight. Mol Plant Microbe Interact. 36(8): 478-488. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-12-22-0254-R

Harris LJ, Balcerzak M, A Johnston, et al. (2016) Host-preferential Fusarium graminearum gene expression during infection of wheat, barley, and maize. Fungal Biology 120(1): 111-123. doi: 10.1016/j.funbio.2015.10.010

Hellin P, Duvivier M, Dedeurwaerder G, et al. (2018) Evaluation of the temporal distribution of Fusarium graminearum airborne inoculum above the wheat canopy and its relationship with Fusarium head blight and DON concentration. European Journal of Plant Pathology pp 1–16. doi: 10.1007/s10658-018-1442-7

, , , et al. (2023) Deacetylation of chitin oligomers by Fusarium graminearum polysaccharide deacetylase suppresses plant immunity. Molecular Plant Pathology 24: 1495–1509. doi: 10.1111/mpp.13387

Jansen C, von Wettstein D, Schäfer W, et al. (2005) Infection patterns in barley and wheat spikes inoculated with wild-type and trichodiene synthase gene disrupted Fusarium graminearum. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 102(46): 16892-16897. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0508467102

Ji F, He D, Olaniran AO, et al. (2019) Occurrence, toxicity, production and detection of Fusarium mycotoxin: a review. Food Production, Processing and Nutrition 1, 6. doi: 10.1186/s43014-019-0007-2

Karlsson I, Persson P, Friberg H (2021) Fusarium Head Blight From a Microbiome Perspective. Front. Microbiol. 12: 628373. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2021.628373

Karmacharya A, Li D, Leng Y, et al. (2023) Targeting Disease Susceptibility Genes in Wheat Through wide Hybridization with Maize Expressing Cas9 and Guide RNA. Mol Plant Microbe Interact. 36(9): 554-557. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-01-23-0004-SC

Keller MD, Bergstrom GC, Shields EJ (2014) The aerobiology of Fusarium graminearum. Aerobiologia 30: 123–136. doi: 10.1007/s10453-013-9321-3

Khaledi N, Taheri P, Falahati Rastegar M (2017) Identification, virulence factors characterization, pathogenicity and aggressiveness analysis of Fusarium spp., causing wheat head blight in Iran. European Journal of Plant Pathology 147, 897–918. doi: 10.1007/s10658-016-1059-7

King R, Urban M, Hammond-Kosack MC, Hassani-Pak K, Hammond-Kosack KE (2015) The completed genome sequence of the pathogenic ascomycete fungus Fusarium graminearum. BMC Genomics 16(1): 544. doi: 10.1186/s12864-015-1756-1

Koch A, Kumar N, Weber L, Keller H, Imani J, Kogel KH (2013) Host-induced gene silencing of cytochrome P450 lanosterol C14α-demethylase–encoding genes confers strong resistance to Fusarium species. PNAS 110(48): 19324-19329. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1306373110

Krishnan SV, Anaswara PA, Nampoothiri KM, et al. (2025) Biocontrol Activity of New Lactic Acid Bacteria Isolates Against Fusaria and Fusarium Mycotoxins. Toxins 17(2): 68. doi: 10.3390/toxins17020068

Kriss AB, Paul PA, Xu X, et al. (2012) Quantification of the relationship between the environment and Fusarium head blight, Fusarium pathogen density, and mycotoxins in winter wheat in Europe. Eur J Plant Pathol 133: 975–993. 10.1007/s10658-012-9968-6

Kumar J, Rai KM, Pirseyedi S, et al. (2020) Epigenetic regulation of gene expression improves Fusarium head blight resistance in durum wheat. Sci Rep 10: 17610. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-73521-2

Li G, Yuan Y, Zhou J, et al. (2023) FHB resistance conferred by Fhb1 is under inhibitory regulation of two genetic loci in wheat (Triticum aestivum L.). Theor Appl Genet. 136(6): 134. doi: 10.1007/s00122-023-04380-4

Logrieco A, Battilani P, Camardo Leggieri M, et al. (2021) Perspectives on Global Mycotoxin Issues and Management From the MycoKey Maize Working Group. Plant Disease. doi: 10.1094/PDIS-06-20-1322-FE

Leplat, J., Mangin, P., Falchetto, L. et al. (2018) Visual assessment and computer–assisted image analysis of Fusarium head blight in the field to predict mycotoxin accumulation in wheat grains. European Journal of Plant Pathology 150: 1065–1081. doi: 10.1007/s10658-017-1345-z

Leslie JF, Moretti A, Mesterházy Á, et al. (2021) Key Global Actions for Mycotoxin Management in Wheat and Other Small Grains. Toxins 13(10): 725. doi: 10.3390/toxins13100725

Lofgren LA, LeBlanc NR, Certano AK, et al. (2017) Fusarium graminearum: pathogen or endophyte of North American grasses?. New Phytologist (online) doi: 10.1111/nph.14894

Machado FJ, Santana FM, Lau D, Del Ponte EM (2017) Quantitative Review of the Effects of Triazole and Benzimidazole Fungicides on Fusarium Head Blight and Wheat Yield in Brazil. Plant Disease 101(9): 1633-1641. doi: 10.1094/PDIS-03-17-0340-RE

Machado FJ, Silva CN, Paiva GF, et al. (2023) Sensitivity to tebuconazole and carbendazim in Fusarium graminearum species complex populations causing wheat head blight in southern Brazil. Trop. plant pathol. doi: 10.1007/s40858-023-00616-2

Mahmoud AF (2016) Genetic Variation and Biological Control of Fusarium graminearum Isolated from Wheat in Assiut-Egypt. The Plant Pathology Journal 32(2): 145-56. doi: 10.5423/PPJ.OA.09.2015.0201

Makhlouf KE, Boungab K, Mokrani S (2023) Synergistic effect of Pseudomonas azotoformans and Trichoderma gamsii in management of Fusarium crown rot of wheat, Archives of Phytopathology and Plant Protection 56: 108-126. doi: 10.1080/03235408.2023.2178056

Malaissi T (2016) Fusariosis de la espiga de trigo: las malezas como fuente de inóculo. Tesis, UNLP. Link

Malla KB, Thapa G, Doohan FM (2021) Mitochondrial phosphate transporter and methyltransferase genes contribute to Fusarium head blight Type II disease resistance and grain development in wheat. PLoS ONE 16(10): e0258726. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0258726

Martinez M, Dinolfo M, Castañares E, Stenglein S (2019) Fusarium graminearum sensu stricto associated with head blight on rye (Secale cereale L.) in Argentina. Journal of Plant Protection Research 59(2): 287-292. doi: 10.24425/jppr.2019.129280

, , , et al. (2023) Weather-based models for forecasting Fusarium head blight risks in wheat and barley: A review. Plant Pathology 00: 1–14. doi: 10.1111/ppa.13839

Mattei V, Motta A, Saracchi M, et al. (2022) Wheat Seed Coating with Streptomyces sp. Strain DEF39 Spores Protects against Fusarium Head Blight. Microorganisms 10(8): 1536. doi: 10.3390/microorganisms10081536

McLaughlin JE, Darwish NI, Garcia-Sanchez J (2021) A Lipid Transfer Protein has Antifungal and Antioxidant Activity and Suppresses Fusarium Head Blight Disease and DON Accumulation in Transgenic Wheat. Phytopathology 111(4): 671-683. doi: 10.1094/PHYTO-04-20-0153-R

, (1997) Scab of wheat and barley: a re-emerging disease of devastating impact. Plant Dis. 81: 1340–1348. doi: 10.1094/PDIS.1997.81.12.1340

Mesterházy Á, Bartók T, Mirocha CG, Komoróczy R (1999) Nature of wheat resistance to Fusarium head blight and the role of deoxynivalenol for breeding. Plant Breeding 118: 97-110. doi: 10.1046/j.1439-0523.1999.118002097.x

Mesterházy Á (2002) Role of Deoxynivalenol in Aggressiveness of Fusarium graminearum and F. culmorum and in Resistance to Fusarium Head Blight. European Journal of Plant Pathology 108: 675. doi: 10.1023/A:1020631114063

Mielniczuk E, Skwaryło-Bednarz B (2020) Fusarium Head Blight, Mycotoxins and Strategies for Their Reduction. Agronomy 10(4): 509. doi: 10.3390/agronomy10040509

Modrzewska M, Bryła M, Kanabus J, Pierzgalski A (2022) Trichoderma as a biostimulator and biocontrol agent against Fusarium in the production of cereal crops: opportunities and possibilities. Plant Pathol. doi: 10.1111/ppa.13578

Moraes WB, Madden LV, Paul PA (2021) Characterizing heterogeneity and determining sample sizes for accurately estimating wheat Fusarium head blight index in research plots. Phytopathology. doi: 10.1094/PHYTO-04-21-0157-R

Moraes WB, Madden LV, Baik BK, et al. (2022) Environmental Conditions after Fusarium Head Blight Visual Symptom Development affect Contamination of Wheat Grain with Deoxynivalenol and Deoxynivalenol-3-Glucoside. Phytopathology. doi: 10.1094/PHYTO-06-22-0199-R

Moschini RC, Martínez MI, Sepulcri MG (2013) Modeling and Forecasting Systems for Fusarium Head Blight and Deoxynivalenol Content in Wheat in Argentina. In: Alconada Magliano TM, Chulze SN, (Eds) Fusarium Head Blight in Latin America. pp. 205-227. Springer Dordrecht. doi: 10.1007/978-94-007-7091-1

Moschini RC, Acuña M, Alberione E, et al. (2016) Validación de sistemas de pronóstico del impacto de la Fusariosis de la espiga en cultivares de trigo. Meteorologica 41(1): 37-46. ISSN 1850-468X

Mourelos CA, Malbrán I, Balatti PA, et al. (2014) Gramineous and non-gramineous weed species as alternative hosts of Fusarium graminearum, causal agent of Fusarium head blight of wheat, in Argentina. Crop Protection 65: 100-104. doi: 10.1016/j.cropro.2014.07.013

O’Donnell K, Whitaker BK, Laraba I, et al. (2022) DNA Sequence-Based Identification of Fusarium: A Work in Progress. Plant Disease 106(6): 1597-1609. doi: 10.1094/PDIS-09-21-2035-SR

O’Mara SP, Broz K, Boenisch M, et al. (2020) The Fusarium graminearum t-SNARE Sso2 Is Involved in Growth, Defense, and DON Accumulation and Virulence. Mol Plant Microbe Interact. 33(7):888-901. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-01-20-0012-R

Oghenekaro AO, Oviedo-Ludena MA, Serajazari M, et al. (2021) Population Genetic Structure and Chemotype Diversity of Fusarium graminearum Populations from Wheat in Canada and North Eastern United States. Toxins 13(3): 180. doi: 10.3390/toxins13030180

Ortega LM, Dinolfo MI, Astoreca AL, et al. (2016) Molecular and mycotoxin characterization of Fusarium graminearum isolates obtained from wheat at a single field in Argentina. Mycological Progress 15: 1. doi: 10.1007/s11557-015-1147-7

Osborne LE, Stein JM (2007) Epidemiology of Fusarium head blight on small-grain cereals. Int J Food Microbiol. 119(1-2): 103-108. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2007.07.032

Palacios SA, Del Canto A, Erazo J, Torres AM (2021) Fusarium cerealis causing Fusarium head blight of durum wheat and its associated mycotoxins. International Journal of Food Microbiology 346: 109161. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2021.109161

Parry DW, Jenkinson P, Mcleod L (1995) Fusarium ear blight (scab) in small grain cereals—a review. Plant Pathology 44: 207-238. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3059.1995.tb02773.x

Paudel B, Pedersen C, Yen Y, Marzano SL (2022) Fusarium graminearum Virus-1 Strain FgV1-SD4 Infection Eliminates Mycotoxin Deoxynivalenol Synthesis by Fusarium graminearum in FHB. Microorganisms 10(8): 1484. doi: 10.3390/microorganisms10081484

Paul PA, Salgado JD, Bergstrom GC, et al. (2018) Integrated Effects of Genetic Resistance and Prothioconazole + Tebuconazole Application Timing on Fusarium Head Blight in Wheat. Plant Disease. doi: 10.1094/PDIS-04-18-0565-RE

Pena GA, Cardenas MA, Monge MP, et al. (2022) Reduction of Fusarium proliferatum growth and fumonisin accumulation by ZnO nanoparticles both on a maize based medium and irradiated maize grains. International Journal of Food Microbiology 363: 109510. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2021.109510

Perincherry L, Lalak-Kańczugowska J, Stępień Ł (2019) Fusarium-Produced Mycotoxins in Plant-Pathogen Interactions. Toxins (Basel): 11(11): 664. doi: 10.3390/toxins11110664

Perochon A, Jianguang J, Kahla A, et al. (2015) TaFROG encodes a Pooideae orphan protein that interacts with SnRK1 and enhances resistance to the mycotoxigenic fungus Fusarium graminearum. Plant Physiology 169(4): 2895-2906. doi: 10.1104/pp.15.01056

Perochon A, Doohan FM (2016) Assessment of Wheat Resistance to Fusarium graminearum by Automated Image Analysis of Detached Leaves Assay. Bio-protocol 6(24): e2065. doi: 10.21769/BioProtoc.2065

Petrucci A, Khairullina A, Sarrocco S, et al. (2023) Understanding the mechanisms underlying biological control of Fusarium diseases in cereals. Eur J Plant Pathol. doi: 10.1007/s10658-023-02753-5

Qiu JB, Sun JT, Yu MZ, et al. (2016) Temporal dynamics, population characterization and mycotoxins accumulation of Fusarium graminearum in Eastern China. Sci Rep 6: 36350. doi: 10.1038/srep36350

Quarantin A, Glasenapp A, Schäfer W, et al. (2016) Involvement of the Fusarium graminearum cerato-platanin proteins in fungal growth and plant infection. Plant Physiol Biochem. 109: 220-229. doi: 10.1016/j.plaphy.2016.10.001

Rauwane ME, Ogugua UV, Kalu CM, et al. (2020) Pathogenicity and Virulence Factors of Fusarium graminearum Including Factors Discovered Using Next Generation Sequencing Technologies and Proteomics. Microorganisms 8, 305. doi: 10.3390/microorganisms8020305

Reis EM, Boareto C, Danelli ALD, Zoldan SM (2016) Anthesis, the infectious process and disease progress curves for fusarium head blight in wheat. Summa Phytopathologica 42(2): 134-139. doi: 10.1590/0100-5405/2075

Risoli S, Petrucci A, Vicente I, Sarrocco S (2023) Trichoderma gamsii T6085, a biocontrol agent of Fusarium head blight, modulates biocontrol-relevant defence gene expression in wheat. Plant Pathol. doi: 10.1111/ppa.13773

Rod KS, Bradley CA, Van Sanford DA and Knott CA (2020) Integrating Management Practices to Decrease Deoxynivalenol Contamination in Soft Red Winter Wheat. Front. Plant Sci. 11: 1158. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2020.01158

Reis EM, Reis AC, Carmona M (2023) Anthesis in small grains and Fusarium head blight infection. Summa phytopathol [Internet] 49: e268456. doi: 10.1590/0100-5405/268456

Rodrigues Duffeck M, Del Ponte EM, Esker P (2021) Multifaceted insights of Fusarium head blight in small grains in Pennsylvania. Plant Health Progress. doi: 10.1094/PHP-03-21-0067-SYN

Rojas EC, Sapkota R, Jensen B, et al. (2020) Fusarium Head Blight Modifies Fungal Endophytic Communities During Infection of Wheat Spikes. Microb Ecol 79: 397–408. doi: 10.1007/s00248-019-01426-3

Rojas EC, Jensen B, Jørgensen HJL, et al. (2022) The Fungal Endophyte Penicillium olsonii ML37 Reduces Fusarium Head Blight by Local Induced Resistance in Wheat Spikes. Journal of Fungi 8(4): 345. doi: 10.3390/jof8040345

Różewicz M, Wyzińska M, Grabiński J (2021) The Most Important Fungal Diseases of Cereals—Problems and Possible Solutions. Agronomy 11(4): 714. doi: 10.3390/agronomy11040714

Ruan Y, Zhang W, Knox RE, et al. (2020) Characterization of the Genetic Architecture for Fusarium Head Blight Resistance in Durum Wheat: The Complex Association of Resistance, Flowering Time, and Height Genes. Front. Plant Sci. 11:592064. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2020.592064

Salgado JD, Madden LV, Paul PA (2014) Efficacy and economics of integrating in-field and harvesting strategies to manage Fusarium head blight of wheat. Plant Disease 98: 1407-1421. doi: 10.1094/PDIS-01-14-0093-RE

Sampietro DA, Belizana MM, Baptista ZP, et al. (2014) Essential oils from Schinus species of northwest Argentina: Composition and antifungal activity. Nat Prod Commun. 9(7): 1019-22. doi: 10.1177/1934578X1400900734

Schoneberg T, Musa T, Forrer HR, et al. (2018) Infection conditions of Fusarium graminearum in barley are variety specific and different from those in wheat. European Journal of Plant Pathology (in press): 1-15. doi: 10.1007/s10658-018-1434-7

Sella L, Gazzetti K, Castiglioni C, et al. (2014) Fusarium graminearum possesses virulence factors common to Fusarium head blight of wheat and seedling rot of soybean but differing in their impact on disease severity. Phytopathology 104: 1201-1207. doi: 10.1094/PHYTO-12-13-0355-R

Semagn K, Iqbal M, Jarquin D, et al. (2022) Genomic Predictions for Common Bunt, FHB, Stripe Rust, Leaf Rust, and Leaf Spotting Resistance in Spring Wheat. Genes 13(4): 565. doi: 10.3390/genes13040565

Shah L, Ali A, Yahya M, et al. (2017) Integrated control of fusarium head blight and deoxynivalenol mycotoxin in wheat. Plant Pathology doi: 10.1111/ppa.12785

Shah DA, De Wolf E, Paul PA, Madden LV (2018) Functional data analysis of weather variables linked to Fusarium head blight epidemics in the United States. Phytopathology. doi: 10.1094/PHYTO-11-17-0386-R

Shah DA, De Wolf ED, Paul PA, Madden LV (2021) Accuracy in the prediction of disease epidemics when ensembling simple but highly correlated models. PLoS Comput Biol 17(3): e1008831. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1008831

Sharma P, Gangola MP, Huang C, et al. (2018) Single nucleotide polymorphisms in B-genome specific UDP-glucosyl transferases associated with fusarium head blight resistance and reduced deoxynivalenol accumulation in wheat grain. Phytopathology 108(1): 124-132. doi: 10.1094/PHYTO-04-17-0159-R

Shi S, Zhao J, Pu L, et al. (2020) Identification of New Sources of Resistance to Crown Rot and Fusarium Head Blight in Wheat. Plant Disease 104(7): 1979-1985. doi: 10.1094/PDIS-10-19-2254-RE

Simpfendorfer S (2016) Evaluation of fungicide timing and preventative application on the control of Fusarium head blight and resulting yield. Australasian Plant Pathology 45: 513-516. doi: 10.1007/s13313-016-0441-4

Singh G, Peng G, Hnatowich G, Kutcher HR (2021) Fungicide Mitigates Fusarium Head Blight in Durum Wheat when Applied as Late as the End of Flowering in Western Canada. Plant Disease. doi: 10.1094/PDIS-02-21-0335-RE

Singh L, Schulden T, Wight JP, et al. (2021) Evaluation of Application Timing of Miravis Ace for Control of Fusarium Head Blight in Wheat. Plant Health Progress 22: 94-100. doi: 10.1094/PHP-01-21-0007-RS

Siou D, Gélisse S, Laval V, et al. (2014) Effect of wheat spike infection timing on fusarium head blight development and mycotoxin accumulation. Plant Pathology 63: 390-399. doi: 10.1111/ppa.12106

Sisson AJ, Allen T, Andersen K, et al. (2025) Estimated yield reductions and economic losses on wheat caused by disease from 2018 through 2021. Plant Health Progress. doi: 10.1094/PHP-09-24-0087-RS

Sorahinobar M, Soltanloo H, Niknam V, et al. (2017) Physiological and molecular responses of resistant and susceptible wheat cultivars to Fusarium graminearum mycotoxin extract. Canadian Journal of Plant Pathology 39(4): 444-453. doi: 0.1080/07060661.2017.1379442

Spagnoletti FN, Carmona M, Balestrasse K, et al. (2021) The arbuscular mycorrhizal fungus Rhizophagus intraradices reduces the root rot caused by Fusarium pseudograminearum in wheat. Rhizosphere 19: 100369. doi: 10.1016/j.rhisph.2021.100369

Strange RN, Majer JR, Smith H (1974) The isolation and identification of choline and betaine as the two major components in anthers and wheat germ that stimulate Fusarium graminearum in vitro. Physiological Plant Pathology 4: 277-290. doi: 10.1016/0048-4059(74)90015-0

Strange RN, Smith H (1978) Specificity of choline and betaine as stimulants of Fusarium graminearum. Transactions of the British Mycological Society 70: 187-192. doi: 10.1016/S0007-1536(78)80029-1

Su Z, Bernardo A, Tian B, et al. (2019) A deletion mutation in TaHRC confers Fhb1 resistance to Fusarium head blight in wheat. Nature Genetics 51(7):1099-1105. doi: 10.1038/s41588-019-0425-8

, , , (2021) A natural two-nucleotide deletion affirms role for NADPH oxidase in pathogenicity and perithecium formation in Fusarium graminearum species complex. Plant Pathology 00: 1– 9. doi: 10.1111/ppa.13499

Taheri P (2018) Cereal diseases caused by Fusarium graminearum: from biology of the pathogen to oxidative burst-related host defense responses. European Journal of Plant Pathology 1–20. doi: 10.1007/s10658-018-1471-2

, , , et al. (2020) At the scene of the crime: New insights into the role of weakly pathogenic members of the fusarium head blight disease complex. Molecular Plant Pathology 21: 1559– 1572. doi: 10.1111/mpp.12996

Tek MI, Budak K (2022) A New Approach to Develop Resistant Cultivars Against the Plant Pathogens: CRISPR Drives. Front. Plant Sci. 13: 889497. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2022.889497

Tomioka K, Kawakami A, Masunaka A, et al. (2021) Head blight of durum wheat caused by Fusarium asiaticum. J Gen Plant Pathol 87: 39–41. doi: 10.1007/s10327-020-00962-y

Tiwari M, Lovelace AH (2023) Unraveling the Function of FgNls1, a Fusarium graminearum Effector Critical for Full Virulence on Wheat. Mol Plant Microbe Interact. 36(8): 476-477. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-06-23-0084-CM

Urban M, Mott E, Farley T, Hammond-Kosack K (2003) The Fusarium graminearum MAP1 gene is essential for pathogenicity and development of perithecia. Molecular Plant Pathology 4: 347–359. doi: 10.1046/j.1364-3703.2003.00183.x

Valentin LR, Vessela A, Alejandro CC, et al. (2025) New insights into the antifungal and anti-mycotoxigenic potential of the TickCore3 peptide against Fusarium species causing Fusarium head blight. J Plant Dis Prot 132: 74. doi: 10.1007/s41348-025-01069-2

Valverde-Bogantes E, Bianchini A, Wegulo SN, Hallen-Adams HE (2021) Species and Trichothecene Genotype of Pathogens Causing Fusarium Head Blight of Wheat in Nebraska, U.S.A. Plant Health Progress 22: 509-515. doi: 10.1094/PHP-02-21-0020-RS

Venturini G, Toffolatti SL, Assante G, et al. (2015) The influence of flavonoids in maize pericarp on fusarium ear rot symptoms and fumonisin accumulation under field conditions. Plant Pathology 64: 671–679. doi: 10.1111/ppa.12304

Vicente I, Quaratiello G, Baroncelli R, et al. (2022) Insights on KP4 Killer Toxin-like Proteins of Fusarium Species in Interspecific Interactions. Journal of Fungi 8(9): 968. doi: 10.3390/jof8090968

, , , et al. (2025) Priority actions for Fusarium head blight resistance in durum wheat: Insights from the wheat initiative. The Plant Genome 18: e20539. doi: 10.1002/tpg2.20539

Wang R, Chen J, Anderson JA, et al. (2017) Genome-Wide Association Mapping of Fusarium Head Blight Resistance in Spring Wheat Lines Developed in the Pacific Northwest and CIMMYT. Phytopathology 107(12): 1486-1495. doi: 10.1094/PHYTO-02-17-0073-R

Wang H, Sun S, Ge W, et al. (2020) Horizontal gene transfer of Fhb7 from fungus underlies Fusarium head blight resistance in wheat. Science 368(6493): eaba5435. doi: 10.1126/science.aba5435

, , , (2022) Diversity of Fusarium community assembly shapes mycotoxin accumulation of diseased wheat heads. Molecular Ecology. doi: 10.1111/mec.16618

West JS, Canning GGM, Perryman SA, et al. (2017) Novel Technologies for the detection of Fusarium head blight disease and airborne inoculum. Tropical Plant Pathology 42(3): 203-209. doi: 10.1007/s40858-017-0138-4

Whitaker BK, Vaughan MM, McCormick SP (2023) Biocontrol Impacts on Wheat Physiology and Fusarium Head Blight Outcomes Are Bacterial Endophyte Strain and Cultivar Specific. Phytobiomes Journal. doi: 10.1094/PBIOMES-08-22-0056-R

Wulff BBH, Jones JDG (2020) Breeding a fungal gene into wheat. Science 368(6493):822-823. doi: 10.1126/science.abb9991

Xu D, Xue M, Shen Z, et al. (2021) Phytotoxic Secondary Metabolites from Fungi. Toxins. 13(4): 261. doi: 10.3390/toxins13040261

Xu X, Nicholson P (2009) Community ecology of fungal pathogens causing wheat head blight. Annu Rev Phytopathol. 2009;47:83-103. doi: 10.1146/annurev-phyto-080508-081737

Xu X, Madden LV, Edwards SG, et al. (2013) Developing logistic models to relate the accumulation of DON associated with Fusarium head blight to climatic conditions in Europe. Eur J Plant Pathol 137: 689–706. doi: 10.1007/s10658-013-0280-x

Xu S, Liu YX, Cernava T, et al. (2022) Fusarium fruiting body microbiome member Pantoea agglomerans inhibits fungal pathogenesis by targeting lipid rafts. Nat Microbiol 7: 831–843. doi: 10.1038/s41564-022-01131-x

Xu M, Wang Q, Wang G, et al. (2022) Combatting Fusarium head blight: advances in molecular interactions between Fusarium graminearum and wheat. Phytopathol Res 4: 37. doi: 10.1186/s42483-022-00142-0

Yang F, Jacobsen S, Jørgensen HJL, et al. (2013) Fusarium graminearum and its interactions with cereal heads: studies in the proteomics era. Frontiers in Plant Science 4: 37. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2013.00037

Yang M, Wang X, Dong J, et al. (2020) Proteomics Reveals the Changes that Contribute to Fusarium Head Blight Resistance in Wheat. Phytopathology: PHYTO05200171R. doi: 10.1094/PHYTO-05-20-0171-R

Ye Z, Brûlé-Babel AL, Graf RJ, Mohr R, Beres BL (2017) The role of genetics, growth habit, and cultural practices in the mitigation of Fusarium head blight. Canadian Journal of Plant Science 97: 316-328. doi: 10.1139/cjps-2016-0336

Yerkovich N, Cantoro R, Palazzini JM, Torres A, Chulze SN (2020) Fusarium head blight in Argentina: Pathogen aggressiveness, triazole tolerance and biocontrol-cultivar combined strategy to reduce disease and deoxynivalenol in wheat. Crop Protection 137: 105300. doi: 10.1016/j.cropro.2020.105300

Yi X, Cheng J, Jiang Z, et al. (2018) Genetic Analysis of Fusarium Head Blight Resistance in CIMMYT Bread Wheat Line C615 Using Traditional and Conditional QTL Mapping. Front. Plant Sci. 9:573. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2018.00573

Zhang L, Sun K, Li Y, et al. (2022) The Importin FgPse1 Is Required for Vegetative Development, Virulence, and Deoxynivalenol Production by Interacting with the Nuclear Polyadenylated RNA-Binding Protein FgNab2 in Fusarium graminearum. Phytopathology 112(5): 1072-1080. doi: 10.1094/PHYTO-08-21-0357-R

Zhanga DY, Chena G, Yin X, et al. (2020) Integrating spectral and image data to detect Fusarium head blight of wheat. Computers and Electronics in Agriculture 175: 105588. doi: 10.1016/j.compag.2020.105588

, , , et al. (2021) Microtubule‐assisted mechanism for toxisome assembly in Fusarium graminearum. Molecular Plant Pathology 22: 163– 174. doi: 10.1111/mpp.13015

Zhou F, Zhou H-H, Han A-H, et al. (2023) Mechanism of Pydiflumetofen Resistance in Fusarium graminearum in China. Journal of Fungi 9(1): 62. doi: 10.3390/jof9010062