.

Condición fitosanitaria: Presente

Grupo de cultivos: Hortícolas

Especie hospedante: Berenjena (Solanum melongena L., 1753)

Rango de hospedantes: específico / estrecho. Las especies de Fusarium oxysporum causan marchitamiento en más de 150 hospedantes y varían con formae speciales específicas (Bertoldo et al., 2015; Jangir et al., 2021).

Etiología: Hongo. Necrotrófico

Agente causal: Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. melongenae

Taxonomía: Fungi > Ascomycota > Pezizomycotina > Sordariomycetes > Hypocreales > Nectriaceae > Fusarium > Fusarium oxysporum species complex > Fusarium oxysporum

.

Fusarium oxysporum es un hongo «habitante» del suelo, que produce dos tipos de esporas asexuales: macroconidios, microconidios y estructuras de resistencia, las clamidosporas.

Los macroconidios son rectos a ligeramente curvados, delgados y de paredes delgadas, generalmente con tres o cuatro septos, una célula basal en forma de pie y una célula apical cónica y curva. Generalmente se producen a partir de fialidas sobre conidióforos por división basípeta. Son importantes en la infección secundaria.

Los microconidios son elipsoidales y no tienen tabique o tienen uno solo. Se forman a partir de fialidas en falsas cabezas por división basípeta. Son importantes en la infección secundaria.

Las clamidosporas son globosas y tienen paredes gruesas. Se forman a partir de hifas o, alternativamente, mediante la modificación de células de hifas. Son importantes como órganos de resistencia en suelos donde actúan como inóculos en la infección primaria.

Se desconoce el teleomorfo o etapa reproductiva sexual de F. oxysporum.

A pesar de que las especies de Fusarium tienen un amplio rango de hospedantes, las especies individuales a menudo se asocian con solo una o unas pocas plantas hospedantes (Li et al., 2020). Así por ejemplo, las poblaciones de F. solani patógenas en plantas se han dividido en 12 formae speciales y dos razas (Šišić et al., 2018; Jangir et al., 2021). Fusarium oxysporum es la especie de Fusarium de mayor importancia económica y más común. Se sabe que este hongo del suelo alberga cepas patógenas (de vegetales, animales y humanos) y no patógenas. Sin embargo, en su concepto actual, F. oxysporum es un complejo de especies que consta de numerosas especies crípticas. La identificación y el nombre de estas especies crípticas se complica por los múltiples sistemas de clasificación subespecíficos y la falta de material vivo de tipo ex que sirva como punto de referencia básico para la inferencia filogenética. Por lo tanto, para avanzar y estabilizar la posición taxonómica de F. oxysporum como especie y permitir el nombramiento de las múltiples especies crípticas reconocidas en este complejo de especies, Lombard et al. (2019) designaron un epitipo para F. oxysporum. Utilizando la inferencia filogenética de múltiples locus y las diferencias morfológicas sutiles con el epitipo recién establecido de F. oxysporum como punto de referencia, pudieron resolver 15 taxones crípticos, descriptas como especies.

Las cepas hospedante-específicas de F. oxysporum se asignan a formae speciales (f. sp.), siguiendo una propuesta de Snyder y Hansen (1940) para tratar tales formas biológicas como variantes de una sola especie, en lugar de taxones separados. La designación de forma specialis no tenía valor taxonómico y era simplemente una agrupación de conveniencia que facilitaba la comunicación entre los fitopatólogos. Sin embargo, estar subsumido bajo un nombre científico implicaba cepas en la misma forma specialis constituía un agrupamiento natural, pero finalmente se hizo evidente que este sistema no es perfecto (O’Donnell et al., 1998; Baayen et al., 2000).

El género Fusarium es una de las especies más complejas y adaptativas en el complejo de especies Eumycota y Fusarium oxysporum (Fo) que incluye patógenos de plantas, animales y humanos y una amplia gama de no patógenos (Nirmaladevi et al., 2016; Gordon, 2017; Jelinski et al., 2017; Jangir et al., 2021).

.

.

.

Síntomas

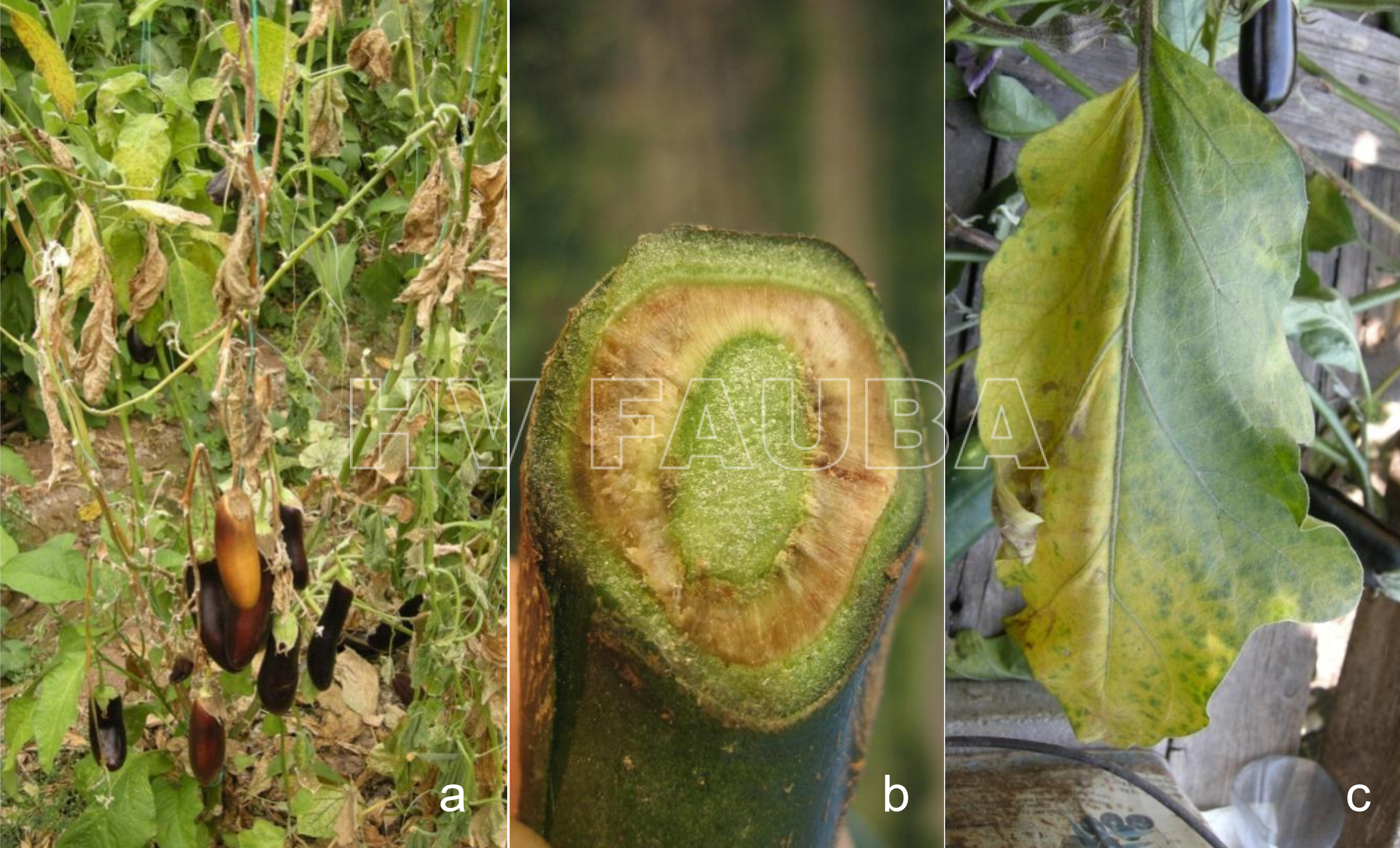

- Síntomas del marchitamiento de la berenjena por Fusarium. Síntomas en: (a) la planta, (b) haces vasculares y (c) hojas. Autor: Yildiz et al 2012

Manejo Integrado

* Plantar cultivares de berenjena resistentes (cuando hubiera disponibles). Se conocen fuentes de resistencia a las tres razas (ver tabla 1 en McGovern, 2015). Las razas 1 y 2 crecen en las regiones productoras de tomate de todo el mundo, mientras que la raza 3 se ha reportado en regiones o países como California, Australia, el suroeste de Georgia y México. La mayoría de las variedades comerciales de tomate cultivadas en todo el mundo son resistentes a las razas 1 y 2, y algunas son resistentes a la raza 3 (Biju et al., 2017).

* Injerto (existen materiales con resistencia a las 3 razas, comercialmente disponibles)

* Solarización

* Desinfección Suelos con fumigantes químicos (ej. 1-3 dicloropropeno)

* Cultivo en Sustrato

* Control biológico (ej. Trichoderma spp. (Debbi et al., 2018), Bacillus spp. (Shahzad et al., 2017), bacterias PGPR (Syed Nabi et al., 2021))

* Inducción de defensas. Se han reportado respuestas de control con aplicaciones de acibenzolar-S-methyl, benzotiadiazol, quitosano, compost, ácido jasmónico, ácido salicílico, validamicina A, silicio al transplante, etc. (ver tabla 2 en McGovern, 2015).

* Tratamientos químicos, en drench al transplante o aplicados en riego por goteo (azoxistrobina, trifloxistrobina, cyprodinil+fludioxonil, pydiflumetofen, difenoconazole, tebuconazole, boscalid+pyraclostrobin)

.

.

Bibliografía

Altimira F, Godoy S, Arias-Aravena M, et al. (2022) Genomic and Experimental Analysis of the Biostimulant and Antagonistic Properties of Phytopathogens of Bacillus safensis and Bacillus siamensis. Microorganisms 10(4): 670. doi: 10.3390/microorganisms10040670

Altinok HH, Can C, Altinok MA (2018) Characterization of Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. melongenae isolates from Turkey with ISSR markers and DNA sequence analyses. Eur J Plant Pathol 150: 609–621. doi: 10.1007/s10658-017-1305-7

Andolfo G, Ferriello F, Tardella L, et al. (2014) Tomato genome-wide transcriptional responses to Fusarium wilt and tomato Mosaic virus. PLoS One 9(5): e94963. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0094963

Baayen RP, O’Donnell K, Bonants PJ, et al. (2000) Gene Genealogies and AFLP Analyses in the Fusarium oxysporum Complex Identify Monophyletic and Nonmonophyletic Formae Speciales Causing Wilt and Rot Disease. Phytopathology 90(8): 891-900. doi: 10.1094/PHYTO.2000.90.8.891

Barocio-Ceja NB, et al. (2013) In vitro biocontrol of tomato pathogens using antagonists isolated from chicken-manure vermicompost. FYTON 82: 15-22. Link

Bartholomew ES, Xu S, Zhang Y, et al. (2022) A chitinase CsChi23 promoter polymorphism underlies cucumber resistance against Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. cucumerinum. New Phytol. doi: 10.1111/nph.18463

Baysal Ö, Siragusa M, Gümrükcü E, et al. (2010) Molecular Characterization of Fusarium oxysporum f. melongenae by ISSR and RAPD Markers on Eggplant. Biochem Genet 48: 524–537. doi: 10.1007/s10528-010-9336-1

Bertoldo C, Gilardi G, Spadaro D, et al. (2015) Genetic diversity and virulence of Italian strains of Fusarium oxysporum isolated from Eustoma grandiflorum. Eur J Plant Pathol 141: 83–97. doi: 10.1007/s10658-014-0526-2

, , , et al (2023) The PTI-suppressing Avr2 effector from Fusarium oxysporum suppresses mono-ubiquitination and plasma membrane dissociation of BIK1. Molecular Plant Pathology 24: 1273–1286. doi: 10.1111/mpp.13369

Biju VC, Fokkens L, Houterman PM, et al. (2017) Multiple Evolutionary Trajectories Have Led to the Emergence of Races in Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. lycopersici. Appl Environ Microbiol. 83(4): e02548-16. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02548-16

Boix-Ruíz A, Gálvez-Patón L, de Cara-García M, et al. (2015) Comparison of analytical techniques used to identify tomato-pathogenic strains of Fusarium oxysporum . Phytoparasitica 43: 471–483.

Bost SC (2001) First Report of Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. lycopersici Race 3 on Tomato in Tennessee. Plant Disease 85(7): 802. doi: 10.1094/PDIS.2001.85.7.802D

Caldwell D, Iyer-Pascuzzi AS (2019) A Scanning Electron Microscopy Technique for Viewing Plant-Microbe Interactions at Tissue and Cell-Type Resolution. Phytopathology 109(7): 1302-1311. doi: 10.1094/PHYTO-07-18-0216-R

Choi HW, Hong SK, Lee YK, Shim HS (2013) First Report of Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. lycopersici Race 3 Causing Fusarium Wilt on Tomato in Korea. Plant Disease 97(10): 1377. doi: 10.1094/PDIS-01-13-0073-PDN

Civieta-Bermejo B, et al. (2021) Residuos de repollo para biocontrol de Fusarium spp. en el cultivo de tomate. Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Agrícolas 26: 95-04. doi: 10.29312/remexca.v0i26.2940

Constantin ME, Fokkens L, de Sain M, et al. (2021) Number of Candidate Effector Genes in Accessory Genomes Differentiates Pathogenic From Endophytic Fusarium oxysporum Strains. Front. Plant Sci. 12: 761740. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2021.761740

Debbi A, Boureghda H, Monte E, Hermosa R (2018) Distribution and Genetic Variability of Fusarium oxysporum Associated with Tomato Diseases in Algeria and a Biocontrol Strategy with Indigenous Trichoderma spp. Front. Microbiol. 9: 282. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2018.00282

Dong Z, Hsiang T, Luo M, Xiang M (2017) Draft Genome Sequence of an Isolate of Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. melongenae, the Causal Agent of Fusarium Wilt of Eggplant. Genome Announc 5(7): e01597-16. doi: 10.1128/genomeA.01597-16

Fuchs JG, Moënne-Loccoz Y, Défago G (1997) Nonpathogenic Fusarium oxysporum strain Fo47 induces resistance to Fusarium wilt in tomato. Plant Disease 81: 492-496. doi: 10.1094/PDIS.1997.81.5.492

Gordon TR (2017) Fusarium oxysporum and the Fusarium Wilt Syndrome. Annu Rev Phytopathol. 55: 23-39. doi: 10.1146/annurev-phyto-080615-095919

Hernández-Aparicio F, Lisón P, Rodrigo I, et al. (2021) Signaling in the Tomato Immunity against Fusarium oxysporum. Molecules 26(7): 1818. doi: 10.3390/molecules26071818

Hirano Y, Arie T (2006) PCR-based differentiation of Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. lycopersici and radicis-lycopersici and races of F. oxysporum f. sp. lycopersici . J Gen Plant Pathology 72: 273–283. doi: 10.1007/s10327-006-0287-7

Huisman OC (1982) Interrelations of root growth dynamics to epidemiology of root-invading fungi. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 20: 303–27.

Inami K, Kashiwa T, Kawabe M, et al. (2014) The tomato wilt fungus Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. lycopersici shares common ancestors with nonpathogenic F. oxysporum isolated from wild tomatoes in the Peruvian Andes. Microbes Environ. 29(2): 200-210. doi: 10.1264/jsme2.ME13184

Jangir P, Mehra N, Sharma K, et al. (2021) Secreted in Xylem Genes: Drivers of Host Adaptation in Fusarium oxysporum. Front. Plant Sci. 12: 628611. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2021.628611

Jelinski NA, Broz K, Jonkers W, et al. (2017) Effector Gene Suites in Some Soil Isolates of Fusarium oxysporum Are Not Sufficient Predictors of Vascular Wilt in Tomato. Phytopathology 107(7): 842-851. doi: 10.1094/PHYTO-12-16-0437-R

Ji HM, Mao HY, Li SJ, et al. (2021) Fol-milR1, a pathogenicity factor of Fusarium oxysporum, confers tomato wilt disease resistance by impairing host immune responses. New Phytol. 232(2): 705-718. doi: 10.1111/nph.17436

Khan M, Khan AU, Bogdanchikova N, Garibo D (2021) Antibacterial and Antifungal Studies of Biosynthesized Silver Nanoparticles against Plant Parasitic Nematode Meloidogyne incognita, Plant Pathogens Ralstonia solanacearum and Fusarium oxysporum. Molecules 26(9): 2462. doi: 10.3390/molecules26092462

Kannan V, Sureendar R (2009) Synergistic effect of beneficial rhizosphere microflora in biocontrol and plant growth promotion. J. Basic Microbiol. 49: 158–164. doi: 10.1002/jobm.200800011

, , , (2021) Target of rapamycin controls hyphal growth and pathogenicity through FoTIP4 in Fusarium oxysporum. Molecular Plant Pathology 00, 1– 17. doi: 10.1111/mpp.13108

, , A single gene in Fusarium oxysporum limits host range. Molecular Plant Pathology 22: 108– 116. doi: 10.1111/mpp.13011

, , , Related mobile pathogenicity chromosomes in Fusarium oxysporum determine host range on cucurbits. Molecular Plant Pathology 21: 761– 776. doi: 10.1111/mpp.12927

Li J, Ma X, Wang C, et al. (2022) Acetylation of a fungal effector that translocates host PR1 facilitates virulence. Elife. 11: e82628. doi: 10.7554/eLife.82628

Lombard L, Sandoval-Denis M, Lamprecht SC, Crous PW (2019) Epitypification of Fusarium oxysporum – clearing the taxonomic chaos. Persoonia 43: 1-47. doi: 10.3767/persoonia.2019.43.01

Lopez-Lima D, Mtz-Enriquez AI, Carrión G, et al. (2021) The bifunctional role of copper nanoparticles in tomato: Effective treatment for Fusarium wilt and plant growth promoter. Scientia Horticulturae 277: 109810. doi: 10.1016/j.scienta.2020.109810

Malbrán I, Mourelos CA, Lori GA (2020) First Report of Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. lycopersici Race 3 Causing Fusarium Wilt of Tomato in Argentina. Plant Disease 104: 978-978. doi: 10.1094/PDIS-08-19-1777-PDN

Maldonado BLD, Villarruel OJL, Calderón OMA, Sánchez EAC (2018) Secreted in xylem (Six) genes in Fusarium oxysporum f.sp. cubense and their potential acquisition by horizontal transfer. Adv. Biotech. Micro. 10 (1): 555779. Link

Marlatt ML, Correll JC, Kaufmann P, Cooper PE (1996) Two genetically distinct populations of Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. lycopersici race 3 in the United States. Plant Disease 80: 1336-1342. doi: 10.1094/PD-80-1336

Mazungunye HT, Ngadze E (2021) Evaluation of Trichoderma Strains as Biocontrol of Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. lycopersici in Tomato. J Plant Pathol Microbiol 12: 571. Link

McGovern RJ (2015) Management of tomato diseases caused by Fusarium oxysporum. Crop Protection 73: 78-92. doi: 10.1016/j.cropro.2015.02.021

Mitidieri MS, et al. (2015) Evaluación de parámetros de rendimiento y sanidad de dos híbridos comerciales de tomate (Solanum lycopersicum L.) injertados sobre Solanum sisymbriifolium (Lam.), en un invernadero con suelo biosolarizado. Horticultura Argentina 34(84): 5-17. Link

Modrzewska M, Bryła M, Kanabus J, Pierzgalski A (2022) Trichoderma as a biostimulator and biocontrol agent against Fusarium in the production of cereal crops: opportunities and possibilities. Plant Pathol. doi: 10.1111/ppa.13578

, (2023) Constitutive activation of TORC1 signalling attenuates virulence in the cross-kingdom fungal pathogen Fusarium oxysporum. Molecular Plant Pathology 24: 289– 301. doi: 10.1111/mpp.13292

Nirmaladevi D, Venkataramana M, Srivastava RK, et al. (2016) Molecular phylogeny, pathogenicity and toxigenicity of Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. lycopersici. Sci Rep. 6: 21367. doi: 10.1038/srep21367

Obregón V (2018) Guía para la identificación de las enfermedades de tomate en invernadero. INTA EEA Bella Vista. Link

O’Donnell K, Kistler HC, Cignelnik E, Ploetz RC (1998) Multiple evolutionary origins of the fungus causing Panama disease of banana: concordant evidence from nuclear and mitochondrial gene genealogies. PNAS 95(5): 2044–49. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.5.2044

O’Donnell K, Whitaker BK, Laraba I, et al. (2022) DNA Sequence-Based Identification of Fusarium: A Work in Progress. Plant Disease 106(6): 1597-1609. doi: 10.1094/PDIS-09-21-2035-SR

Panthee DR, Chen F (2010) Genomics of fungal disease resistance in tomato. Curr. Genomics 11 : 30-39. doi: 10.2174/138920210790217927

Ploetz RC, Haynes JL (2000) First Report of Race 3 of Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. lycopersici in Southeastern Florida. Plant Disease 84(2): 199. doi: 10.1094/PDIS.2000.84.2.199B

Redkar A, Sabale M, Schudoma C, et al. (2022) Conserved secreted effectors contribute to endophytic growth and multi-host plant compatibility in a vascular wilt fungus. Plant Cell.: koac174. doi: 10.1093/plcell/koac174

Reis A, et al. (2005) First report of Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. lycopersici race 3 on tomato in Brazil. Fitopatologia Brasileira 30: 426-428. doi: 10.1590/S0100-41582005000400017

Rep M, Van Der Does HC, Meijer M, et al. (2004) A small, cysteine-rich protein secreted by Fusarium oxysporum during colonization of xylem vessels is required for I-3-mediated resistance in tomato. Molecular Microbiology 53: 1373-1383. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2004.04177.x

Rovira AD (1969) Plant root exudates. Bot. Rev. 35: 35–57.

Sasaki K, Nakahara K, Tanaka S, et al. (2015) Genetic and Pathogenic Variability of Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. cepae Isolated from Onion and Welsh Onion in Japan. Phytopathology 105(4): 525-32. doi: 10.1094/PHYTO-06-14-0164-R

Schmidt SM, Houterman PM, Schreiver I, et al. (2013) MITEs in the promoters of effector genes allow prediction of novel virulence genes in Fusarium oxysporum. BMC Genomics 14: 119. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-14-119

Schmidt SM, Lukasiewicz J, Farrer R, et al. (2016) Comparative genomics of Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. melonis reveals the secreted protein recognized by the Fom-2 resistance gene in melon. New Phytol 209: 307-318. doi: 10.1111/nph.13584

Scott JW, Agrama HA, Jones JP (2004) RFLP-based analysis of recombination among resistance genes to Fusarium wilt Races 1, 2, and 3 in tomato. J. Am. Soc. Hortic. Sci., 129 (3): 394-400. doi: 10.21273/JASHS.129.3.0394

Sepúlveda-Chavera G, Huanca W, Salvatierra-Martínez R, Latorre BA (2014) First Report of Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. lycopersici Race 3 and F. oxysporum f. sp. radicis-lycopersici in Tomatoes in the Azapa Valley of Chile. Plant Disease 98(10): 1432. doi: 10.1094/PDIS-03-14-0303-PDN

Shahzad R, Khan AL, Bilal S, et al. (2017) Plant growth- promoting endophytic bacteria versus pathogenic infections: an example of Bacillus amyloliquefaciens RWL-1 and Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. lycopersici in tomato. Peer J. 5: e3107. doi: 10.7717/peerj.3107

Shanmugam V, Kanoujia N (2011) Biological management of vascular wilt of tomato caused by Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. lycopersici by plant growth-promoting rhizobacterial mixture. Biol. Control 57: 85–93. doi: 10.1016/j.biocontrol.2011.02.001

Snyder WC, Hansen HN (1940) The species concept in Fusarium. Am. J. Bot. 27(2): 64–67.

Srinivas C, Nirmala Devi D, Narasimha Murthy K, et al. (2019) Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. lycopersici causal agent of vascular wilt disease of tomato: Biology to diversity– A review. Saudi Journal of Biological Sciences 26: 1315-1324. doi: 10.1016/j.sjbs.2019.06.002

Srivastava R, Khalid A, Singh US, Sharma AK (2010) Evaluation of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungus, fluorescent Pseudomonas and Trichoderma harzianum formulation against Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. lycopersici for the management of tomato wilt. Biol. Control 53, 24–31. doi: 10.1016/j.biocontrol.2009.11.012

Syed Nabi RB, Shahzad R, Tayade R, et al. (2021) Evaluation potential of PGPR to protect tomato against Fusarium wilt and promote plant growth. PeerJ. 9: e11194. doi: 10.7717/peerj.11194

Takken F, Rep M (2010) The arms race between tomato and Fusarium oxysporum. Molecular Plant Pathology 11: 309-314. doi: 10.1111/j.1364-3703.2009.00605.x

Vicente I, Quaratiello G, Baroncelli R, et al. (2022) Insights on KP4 Killer Toxin-like Proteins of Fusarium Species in Interspecific Interactions. Journal of Fungi. 8(9): 968. doi: 10.3390/jof8090968

Wang L, Calabria J, Chen HW, Somssich M (2022) Overview: The Arabidopsis thaliana – Fusarium oxysporum strain 5176 pathosystem. Journal of Experimental Botany: erac263. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erac263

Yildirim E, Alici E,Erper I, et al. (2022) Sensitivity of Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. melongenae, the causal agent of Fusarium wilt of eggplant to some ammonium, potassium, and sodium compounds in vitro and in vivo bioassays. Archives of Phytopathology and Plant Protection 55: 937-950. doi: 10.1080/03235408.2022.2062538

Yildiz HN, Handan Altinok H, Dikilitas M (2012) Screening of rhizobacteria against Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. melongenae, the causal agent of wilt disease of eggplant. African Journal of Microbiology Research 6(15): 3700-3706. doi: 10.5897/AJMR12.307

Zhou Y, Zhang Z, Bao Z, et al. (2022) Graph pangenome captures missing heritability and empowers tomato breeding. Nature. doi: 10.1038/s41586-022-04808-9