.

Condición fitosanitaria: Presente ampliamente distribuida

Grupo de cultivos: Oleaginosas

Especie hospedante: Soja (Glycine max)

Rango de hospedantes: no específico / amplio. S. sclerotiorum es un hongo polífago con un amplio rango de hospedantes y de amplia difusión mundial, siendo el agente causal de podredumbres en diversos cultivos de importancia económica. Se han reportado más de 408 especies de plantas atacadas por S. sclerotiorum, de 278 géneros, en 75 familias. La mayoría de estas especies son dicotiledóneas, aunque también son hospedantes varias plantas monocotiledóneas de importancia agrícola (Boland & Hall, 1994; Bolton et al., 2006; Derbyshire et al., 2022). El grado de susceptibilidad a S. sclerotiorum en las poblaciones de plantas hospedantes a menudo varía considerablemente. Sin embargo, no existe una resistencia completa a S. sclerotiorum en ninguna especie hospedante.

Se han reportado más de 408 especies de plantas atacadas por S. sclerotiorum, de 278 géneros, en 75 familias (Boland & Hall, 1994). Entre las Familias de plantas hospedantes de Scleorotinia sclerotiorum se encuentran:

Actinidiaceae, Aizoaceae, Amaranthaceae, Annonaceae, Apocynaceae, Araliaceae, Aristolochiaceae, Asclepiadaceae, Begoniaceae, Berberidaceae, Boraginaceae, Campanulaceae, Capparidaceae, Caryophyllaceae, Chenopodiaceae, Compositae, Convolvulaceae, Cruciferae, Cucurbitaceae, Dipsacaceae, Euphorbiaceae, Fagaceae, Fumariaceae, Gentianaceae, Geraniaceae, Gesneriaceae, Gramineae, Hippocastanaceae, Iridaceae, Labiatae, Lauraceae, Leguminosae, Liliaceae, Linaceae, Malvaceae, Martyniaceae, Moraceae, Musaceae, Myoporaceae, Myrtaceae, Oleaceae, Onagraceae, Orobanchaceae, Papaveraceae, Passifloraceae, Pinaceae, Plantaginaceae, Polemoniaceae, Polygonaceae, Portulacaceae, Ranunculaceae, Rosaceae, Rutaceae, Saxifragaceae, Scrophulariaceae, Solanaceae, Theaceae, Tilliaceae, Tropaeolaceae, Umbelliferae, Urticaceae, Valerianaceae, Violaceae, Vitaceae.

Las gramíneas maíz, trigo, cebada, avena, sorgo no son susceptibles a la infección.

.

Epidemiología: monocíclica, subaguda.

Etiología: Hongo. Necrotrófico, con capacidad de supervivencia en el suelo.

Agente causal: Sclerotinia sclerotiorum (Lib.) de Bary (1884)

Taxonomía: Eukaryota > Fungi > Dikarya > Ascomycota > Pezizomycotina > Leotiomycetes > Helotiales > Sclerotiniaceae > Sclerotinia

.

- Semillas de soja colonizadas por cepa virulenta de Sclerotinia sclerotiorum, con formación de esclerocios luego de 7 días de incubación en agar papa glucosa. Autores: Dr Francisco Sautua, Dr Marcelo Carmona

- Autor: Dra. Verónica Felipe, Dr. Francicco Sautua

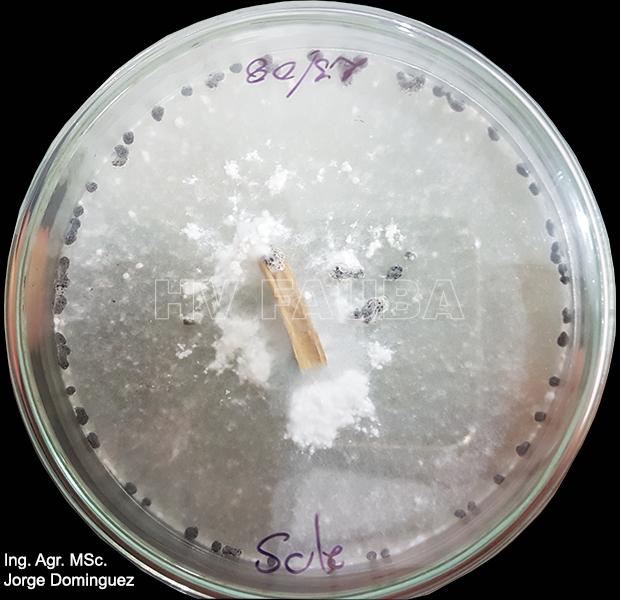

- Sclerotinia sclerotiorum en medio de cultivo especifico (Bromophenol Blue). Autor: Ing. Agr. MSc. Jorge Dominguez

.

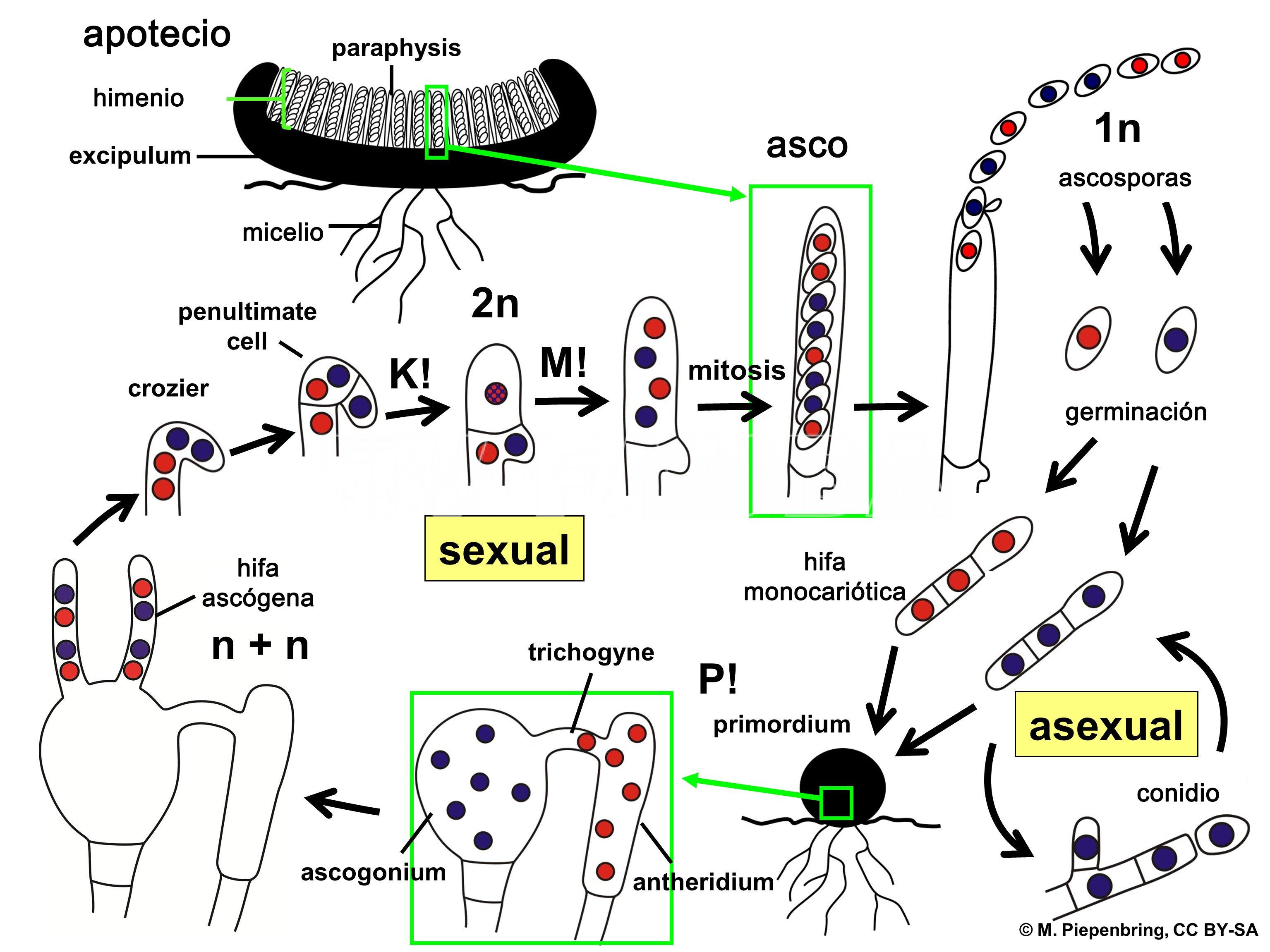

Las especies de Sclerotinia spp. no se reproducen en forma asexual (no forman conidios).

.

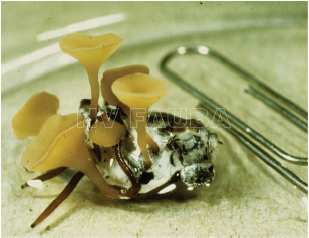

- Apotecios de S. sclerotiorum emergiendo de un esclerocio. Autor: James Venette (publicado en Peltier et al., 2012)

- Autor: Dra. Verónica Felipe, Dr. Francicco Sautua

- Autor: Dra. Verónica Felipe, Dr. Francicco Sautua

- Autor: Dra. Verónica Felipe, Dr. Francicco Sautua

.

.

Síntomas

Causa podredumbre húmeda de todos los órganos que ataca. Es común observar tallos muertos que se vuelven blanquecinos y quebradizos, con las hojas marchitas y adheridas al tallo. Las lesiones generalmente se observan en la parte media y superior de los tallos. En condiciones de alta humedad, se produce desarrollo miceliar (blanco, de aspecto algodonoso) con formación de esclerocios (cuerpos de resistencia, oscuros y duros) en el interior y exterior. Las vainas pueden quedar vanas o presentar granos pequeños y deformes. La enfermedad puede provocar la muerte de plantas a partir de floración. Las semillas de las vainas enfermas generalmente se arrugan y pueden ser infectadas por el hongo o reemplazadas por esclerocios negros. La semilla suele estar contaminada con esclerocios cuando se cosechan plantas infectadas. Los daños causados por la enfermedad están relacionados con el menor número y peso de los granos y la contaminación de los mismos con esclerocios.

.

- Signo (micelio) de Sclerotinia sclerotium en soja. Autor: Daren Mueller, Iowa State University

.

Condiciones ambientales predisponentes para el establecimiento de la enfermedad

Condiciones húmedas y frescas, y cultivos con canopeo denso son factores predisponentes que junto al potencial de inoculo en el suelo (elevada concentración de esclerocios) determinan la severidad de la enfermedad.

.

- Representación esquemática del ciclo de vida de Sclerotinia sclerotiorum. P! = plasmogamia; K! = cariogamia; M! = meiosis; 2n = células diploides; 1n = células haploides; n + n = células dicarióticas. Autor: M. Piepenbring

.

.

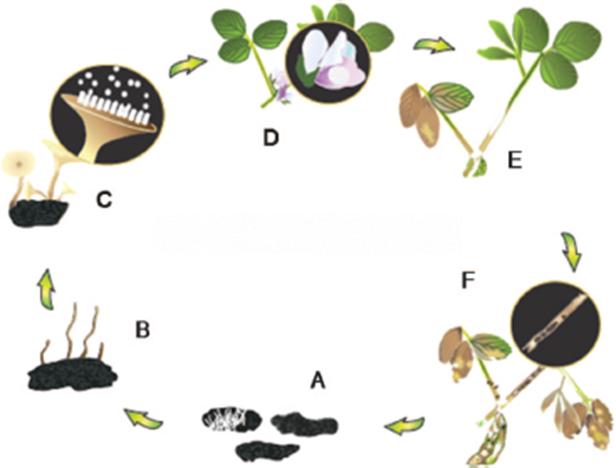

- Ciclo de la la pudrición del tallo por Sclerotinia. (A) Los esclerocios de Sclerotinia sclerotiorum sobreviven en el suelo. (B) En condiciones ambientales frescas y húmedas, los esclerocios germinan para producir apotecios. (C) El apotecio produce esporas sexuales llamadas ascosporas, que se descargan al aire por la fuerza de la eyección desde el apotecio. (D) Las ascosporas colonizan las flores senescentes y la infección puede extenderse al tallo en el nodo. (E) Los signos de S. sclerotiorum incluyen esclerocios y micelio blanco. Los síntomas pueden incluir lesiones “húmedas” en el tallo, marchitez y muerte de la planta, lo que resulta en la ausencia de semillas o un llenado deficiente de las vainas. (F) Los esclerocios se forman dentro y fuera de tallos y vainas y se caen al suelo durante la cosecha (ilustración: Renée Tesdall). Autor: Peltier et al. 2012. Publicado por Oxford University Press on behalf of Entomological Society of America

.

Importancia relativa

La enfermedad causa mayores daños en variedades más ramificadas, con altas densidades de siembra, y ciclos largos. En años lluviosos las pérdidas son mayores. Si bien actualmente esta enfermedad ya no es más importante, se observaron ataques de Sclerotinia sclerotiorum en 2013/14 especialmente en condiciones de canopia densa, ambiente húmedo y bajas temperaturas en los meses de febrero a abril. La podredumbre húmeda del tallo (PHT) es una enfermedad importante no sólo en soja, sino también en girasol, poroto, tomate, colza, alfalfa y otras numerosas especies.

.

- Esclerocios de Sclerotinia sclerotium incrustados en tallo infectado de soja. Autor: Daren Mueller, Iowa State University

.

Manejo de la enfermedad

El hongo forma estructuras de resistencia (esclerocios) que le permiten vivir libre en el suelo aún en ausencia de alguno de sus hospedantes durante varios años. Los esclerocios permanecen alojados en el suelo y el rastrojo, pero también pueden acompañar a la semilla (contaminación concomitante), constituyen el inoculo primario. Las prácticas de control para S. sclerotiorum deberán aplicarse en forma integrada desarrollando una estrategia eficiente. Entre ellas se encuentran: la rotación con cultivos no susceptibles (gramíneas) por al menos tres años, elección de genotipos con buen comportamiento frente a S. sclerotiorum, utilización de semillas desinfectadas, la regulación del espaciamiento y densidad de siembra (de manera de evitar canopeos densos para favorecer la aireación y mantener menor nivel de humedad en el entresurco disminuyendo la posibilidad de infección), genotipos menos ramificados con mayor resistencia al vuelco y más erectos, variedades de ciclos cortos y siembras tempranas (con el objetivo de evitar que coincida el período de floración con condiciones de temperatura y humedad favorables para el inicio de la infección), eliminación de las malezas que actúan como reservorios, regulación del riego para evitar períodos de alta humedad relativa durante el período de infección.

.

- Tallo de soja con crecimiento algodonoso (micelial) blanquecino característico de S. sclerotiorum. Autor. Ing. Agr. MS. Jorge Dominguez..

- Autor: Paul Esker

- Autor: Paul Esker

- Autor: Paul Esker

.

.

Bibliografía

Albert D, Dumonceaux T, Carisse O, et al. (2022) Combining Desirable Traits for a Good Biocontrol Strategy against Sclerotinia sclerotiorum. Microorganisms 10(6): 1189. doi: 10.3390/microorganisms10061189

Amselem J, Cuomo CA, van Kan JAL, et al. (2011) Genomic analysis of the necrotrophic fungal pathogens Sclerotinia sclerotiorum and Botrytis cinerea. PLoS Genetics 7, e1002230. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002230

Boland GJ, Hall R (1994) Index of plant hosts of Sclerotinia sclerotiorum. Canadian Journal of Plant Pathology 16: 93-108. doi: 10.1080/07060669409500766

Bolton MD, Thomma BPHJ, Nelson BD (2006) Sclerotinia sclerotiorum (Lib.) de Bary: biology and molecular traits of a cosmopolitan pathogen. Molecular Plant Pathology 7: 1-16. doi: 10.1111/j.1364-3703.2005.00316.x

Botelho SL, Barrocas EN, Machado JC, Martins RS (2015) Detection of Sclerotinia sclerotiorum in soybean seeds by conventional and quantitative PCR techniques. Journal of Seed Science 37(1): 55-62. doi: 10.1590/2317-1545v37n1141460

Cao Y, Zhang X, Song X, et al. (2024) Efficacy and toxic action of the natural product natamycin against Sclerotinia sclerotiorum. Pest Manag Sci. 10.1002/ps.7930

Carpenter KA, Sisson AJ, Kandel YR, et al. (2021) Effects of Mowing, Seeding Rate, and Foliar Fungicide on Soybean Sclerotinia Stem Rot and Yield. Plant Health Progress 22: 129-135. doi: 10.1094/PHP-11-20-0097-RS

Dann E, Diers B, Byrum J., et al. (1998) Effect of treating soybean with 2,6-dichloroisonicotinic acid (INA) and benzothiadiazole (BTH) on seed yields and the level of disease caused by Sclerotinia sclerotiorum in field and greenhouse studies. European Journal of Plant Pathology 104: 271–278. doi: 10.1023/A:1008683316629

Dean R, Van Kan JAL, Pretorius ZA, et al. (2012). The Top 10 fungal pathogens in molecular plant pathology. Molecular Plant Pathology 13: 414–430. doi: 10.1111/j.1364-3703.2011.00783.x

, , (2022) The evolutionary and molecular features of the broad-host-range plant pathogen Sclerotinia sclerotiorum. Molecular Plant Pathology 00: 1– 16. doi: 10.1111/mpp.13221

El-Ashmony RMS, Zaghloul NSS, Milošević M, et al. (2022) The Biogenically Efficient Synthesis of Silver Nanoparticles Using the Fungus Trichoderma harzianum and Their Antifungal Efficacy against Sclerotinia sclerotiorum and Sclerotium rolfsii. Journal of Fungi. 8(6): 597. doi: 10.3390/jof8060597

Faria AF, Schulman P, Meyer MC, et al. (2025) Seven years of white mold biocontrol product’s performance efficacy on Sclerotinia sclerotiorum carpogenic germination in Brazil: A meta-analysis. Biological Control 176: 105080. doi: 10.1016/j.biocontrol.2022.105080

Gambhir N, Kamvar ZN, Higgins R, et al. (2020) Spontaneous and Fungicide-Induced Genomic Variation in Sclerotinia sclerotiorum. Phytopathology. doi: 10.1094/PHYTO-10-20-0471-FI

Garg H, Li H, Sivasithamparam K, Barbetti MJ (2013) Differentially Expressed Proteins and Associated Histological and Disease Progression Changes in Cotyledon Tissue of a Resistant and Susceptible Genotype of Brassica napus Infected with Sclerotinia sclerotiorum. PLoS ONE 8(6): e65205. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0065205

Godoy CL, Koga LJ, Oliveira MCN, et al. (2017) Mycelial growth, pathogenicity, aggressiveness and apothecial development of Sclerotinia sclerotiorum isolates from Brazil and the United States in contrasting temperature regimes. Summa Phytopathologica 43(4): 263-268. doi: 10.1590/0100-5405/2188

Grabicoski EMG, Jaccoud Filho DS, Pileggi M, et al. (2015) Rapid PCR-based assay for Sclerotinia sclerotiorum detection on soybean seeds. Scientia Agricola 72(1): 69-74. doi: 10.1590/0103-9016-2013-0395

Hartman GL, Kull L, Huang YH (1998) Occurrence of Sclerotinia sclerotiorum in Soybean Fields in East-Central Illinois and Enumeration of Inocula in Soybean Seed Lots. Plant Dis. 82(5): 560-564. doi: 10.1094/PDIS.1998.82.5.560

Hossain MM, Sultana F, Rubayet MT, et al. (2025) White Mold: A Global Threat to Crops and Key Strategies for Its Sustainable Management. Microorganisms 13(1): 4. doi: 10.3390/microorganisms13010004

, , , Genome‐wide alternative splicing profiling in the fungal plant pathogen Sclerotinia sclerotiorum during the colonization of diverse host families. Mol Plant Pathology 22: 31– 47. doi: 10.1111/mpp.13006

Kamal MM, Savocchia S, Lindbeck KD, et al. (2016) Biology and biocontrol of Sclerotinia sclerotiorum (Lib.) de Bary in oilseed Brassicas. Australasian Plant Pathol. 45: 1–14. doi: 10.1007/s13313-015-0391-2

Kusch S, Larrouy J, Ibrahim HMM, et al. (2021) Transcriptional response to host chemical cues underpins the expansion of host range in a fungal plant pathogen lineage. ISME J. doi: 10.1038/s41396-021-01058-x

Lehner MS, Pethybridge SJ, Meyer MC, Del Ponte EM (2017) Meta‐analytic modelling of the incidence–yield and incidence–sclerotial production relationships in soybean white mould epidemics. Plant Pathology 66: 460-468. doi: 10.1111/ppa.12590

Lehner MDS, Alves K, Del Ponte EM, Pethybridge SJ (2021) Comparing the Fungicide Sensitivity of Sclerotinia sclerotiorum Using Mycelial Growth and Ascospore Germination Assays. Plant Disease. doi: 10.1094/PDIS-06-21-1234-SC

O’Sullivan CA, Belt K, Thatcher LF (2021) Tackling Control of a Cosmopolitan Phytopathogen: Sclerotinia. Front. Plant Sci. 12: 707509. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2021.707509

Peltier AJ, Bradley CA, Chilvers MI, et al. (2012) Biology, Yield loss and Control of Sclerotinia Stem Rot of Soybean. Journal of Integrated Pest Management 3: B1–B7. doi: 10.1603/IPM11033

Macena AMF, Kobori NN, Mascarin GM, et al. (2020) Antagonism of Trichoderma-based biofungicides against Brazilian and North American isolates of Sclerotinia sclerotiorum and growth promotion of soybean. BioControl 65: 235–246. doi: 10.1007/s10526-019-09976-8

Mbengue M, Navaud O, Peyraud R, et al. (2016) Emerging Trends in Molecular Interactions between Plants and the Broad Host Range Fungal Pathogens Botrytis cinerea and Sclerotinia sclerotiorum. Frontiers in Plant Science 7: 422. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2016.00422

McCaghey M, Willbur J, Ranjan A, et al. (2017) Development and evaluation of Glycine max germplasm lines with quantitative resistance to Sclerotinia sclerotiorum. Frontiers in Plant Science 8: 1–13. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2017.01495

McCaghey M, Shao D, Kurcezewski J, et al. (2021) Host-Induced Gene Silencing of a Sclerotinia sclerotiorum oxaloacetate acetylhydrolase Using Bean Pod Mottle Virus as a Vehicle Reduces Disease on Soybean. Front. Plant Sci. 12: 677631. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2021.677631

Mei J, Ding Y, Li Y, et al. (2016) Transcriptomic comparison between Brassica oleracea and rice (Oryza sativa) reveals diverse modulations on cell death in response to Sclerotinia sclerotiorum. Sci Rep 6: 33706. doi: 10.1038/srep33706

Miorini TJJ, Raetano CG, Negrisoli MM, et al. (2021) Determination of the protection period of fungicides used for control of Sclerotinia stem rot in soybean through bioassay and chromatography. Eur J Plant Pathol. doi: 10.1007/s10658-021-02212-z

Moellers TC, Singh A, Zhang J, et al. (2017) Main and epistatic loci studies in soybean for Sclerotinia sclerotiorum resistance reveal multiple modes of resistance in multi-environments. Nature Scientific Reports 7, Article number: 3554. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-03695-9

Mukherjee S, Beligala G, Feng C, Marzano SY (2024) Double-Stranded RNA Targeting White Mold Sclerotinia sclerotiorum Argonaute 2 for Disease Control via Spray-Induced Gene Silencing. Phytopathology 114(6): 1253-1262. doi: 10.1094/PHYTO-11-23-0431-R

Nieto-López EH, Miorini TJJ, Wulkop-Gil CA, et al. (2023) Fungicide sensitivity of Sclerotinia sclerotiorum from U.S. soybean and dry bean, compared to different regions and climates. Plant Dis. doi: 10.1094/PDIS-07-22-1707-RE

(1979) Sclerotinia sclerotiorum: history, diseases and symptomatology, host range, geographic distribution, and impact. Phytopathology 69: 875–880. doi: 10.1094/Phyto-69-875

Ranjan A, Jayaraman D, Grau C, et al. (2018) The pathogenic development of Sclerotinia sclerotiorum in soybean requires specific host NADPH oxidases. Molecular Plant Pathology 19: 700–714. doi: 10.1111/mpp.12555

Ranjan A, Westrick NM, Jain S, et al. (2019) Resistance against Sclerotinia sclerotiorum in soybean involves a reprogramming of the phenylpropanoid pathway and up-regulation of antifungal activity targeting ergosterol biosynthesis. Plant Biotechnol J 17: 1567-1581. doi: 10.1111/pbi.13082

(2022) Predicting field diseases caused by Sclerotinia sclerotiorum: A review. Plant Pathology 00: 1– 16. doi: 10.1111/ppa.13643

, , , et al. (2024) Predicting airborne ascospores of Sclerotinia sclerotiorum through machine learning and statistical methods. Plant Pathology 00: 1–16. doi: 10.1111/ppa.13902

Saharan GS, Mehta N (2008) Sclerotinia Diseases of Crop Plants: Biology, Ecology and Disease Management. Springer, Dordrecht. 485 p. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4020-8408-9

, , , et al (2024) The schizotrophic lifestyle of Sclerotinia sclerotiorum. Molecular Plant Pathology 25: e13423. doi: 10.1111/mpp.13423

Singh M, Avtar R, Lakra N, et al. (2021) Genetic and Proteomic Basis of Sclerotinia Stem Rot Resistance in Indian Mustard [Brassica juncea (L.) Czern & Coss.]. Genes 12(11): 1784. doi: 10.3390/genes12111784

Smolińska U, Kowalska B (2018) Biological control of the soil-borne fungal pathogen Sclerotinia sclerotiorum – a review. J Plant Pathol 100: 1–12. doi: 10.1007/s42161-018-0023-0

Willbur J, McCaghey M, Kabbage M, et al. (2018) An overview of the Sclerotinia sclerotiorum pathosystem in soybean: impact, fungal biology, and current management strategies. Tropical Plant Pathology pp 1–9. doi: 10.1007/s40858-018-0250-0

Willbur JF, Fall ML, Bloomingdale C, et al. (2018) Weather-Based Models for Assessing the Risk of Sclerotinia sclerotiorum Apothecial Presence in Soybean (Glycine max) Fields. Plant Disease 102(1): 73-84. doi: 10.1094/PDIS-04-17-0504-RE

Taylor A, Coventry E, Handy C, et al. (2018) Inoculum potential of Sclerotinia sclerotiorum sclerotia depends on isolate and host plant. Plant Pathology (in press). doi: 10.1111/ppa.12843

Webster RW, McCaghey M, Kabbage M, et al. (2023) Creation of New Soybean Varieties with High Levels of Resistance to White Mold. Crop Protection Network. Link

Wei W, Xu L, Peng H, et al. (2022) A fungal extracellular effector inactivates plant polygalacturonase-inhibiting protein. Nat Commun 13: 2213. doi: 10.1038/s41467-022-29788-2

Xu L, Li G, Jiang D, Chen W (2018) Sclerotinia sclerotiorum: An Evaluation of Virulence Theories. Annual Review of Phytopathology 56: 311-338. doi: 10.1146/annurev-phyto-080417-050052

Yang XB, Workneh F, Lundeen P (1998) First Report of Sclerotium Production by Sclerotinia sclerotiorum in Soil on Infected Soybean Seeds. Plant Dis. 82(2): 264. doi: 10.1094/PDIS.1998.82.2.264B

Yu S-F, Wang C-L, Hu Y-F, et al. (2022) Biocontrol of Three Severe Diseases in Soybean. Agriculture 12(9): 1391. doi: 10.3390/agriculture12091391

Zeng W, Wang D, Kirk W, Hao J (2012) Use of Coniothyrium minitans and other microorganisms for reducing Sclerotinia sclerotiorum. Biol Control 60: 225–232. doi: 10.1016/j.biocontrol.2011.10.009

Zhang M, Liu Y, Li Z (2021) The bZIP transcription factor GmbZIP15 facilitates resistance against Sclerotinia sclerotiorum and Phytophthora sojae infection in soybean. iScience 24(6): 102642. doi: 10.1016/j.isci.2021.102642

Zhao X, Han Y, Li Y, et al. (2015) Loci and candidate gene identification for resistance to Sclerotinia sclerotiorum in soybean (Glycine max L. Merr.) via association and linkage maps. The Plant Journal 82: 245–255. doi: 10.1111/tpj.12810