.

Condición fitosanitaria: Presente ampliamente distribuida

Grupo de cultivos: Hortícolas

Especie hospedante: zucchini (Cucurbita pepo var. melopepo)

Rango de hospedantes: no específico / amplio. S. sclerotiorum es un hongo polífago con un amplio rango de hospedantes y de amplia difusión mundial, siendo el agente causal de podredumbres en diversos cultivos de importancia económica. Se han reportado más de 408 especies de plantas atacadas por S. sclerotiorum, de 278 géneros, en 75 familias. La mayoría de estas especies son dicotiledóneas, aunque también son hospedantes varias plantas monocotiledóneas de importancia agrícola (Boland & Hall, 1994; Bolton et al., 2006; Derbyshire et al., 2022). El grado de susceptibilidad a S. sclerotiorum en las poblaciones de plantas hospedantes a menudo varía considerablemente. Sin embargo, no existe una resistencia completa a S. sclerotiorum en ninguna especie hospedante.

Se han reportado más de 408 especies de plantas atacadas por S. sclerotiorum, de 278 géneros, en 75 familias (Boland & Hall, 1994). Entre las Familias de plantas hospedantes de Scleorotinia sclerotiorum se encuentran:

Actinidiaceae, Aizoaceae, Amaranthaceae, Annonaceae, Apocynaceae, Araliaceae, Aristolochiaceae, Asclepiadaceae, Begoniaceae, Berberidaceae, Boraginaceae, Campanulaceae, Capparidaceae, Caryophyllaceae, Chenopodiaceae, Compositae, Convolvulaceae, Cruciferae, Cucurbitaceae, Dipsacaceae, Euphorbiaceae, Fagaceae, Fumariaceae, Gentianaceae, Geraniaceae, Gesneriaceae, Gramineae, Hippocastanaceae, Iridaceae, Labiatae, Lauraceae, Leguminosae, Liliaceae, Linaceae, Malvaceae, Martyniaceae, Moraceae, Musaceae, Myoporaceae, Myrtaceae, Oleaceae, Onagraceae, Orobanchaceae, Papaveraceae, Passifloraceae, Pinaceae, Plantaginaceae, Polemoniaceae, Polygonaceae, Portulacaceae, Ranunculaceae, Rosaceae, Rutaceae, Saxifragaceae, Scrophulariaceae, Solanaceae, Theaceae, Tilliaceae, Tropaeolaceae, Umbelliferae, Urticaceae, Valerianaceae, Violaceae, Vitaceae.

Epidemiología: monocíclica, subaguda.

Etiología: Hongo. Necrotrófico, con capacidad de supervivencia en el suelo.

Agente causal: Sclerotinia sclerotiorum (Lib) de Bary. (1884)

Taxonomía: Eukaryota > Fungi > Dikarya > Ascomycota > Pezizomycotina > Leotiomycetes > Helotiales > Sclerotiniaceae > Sclerotinia

.

.

La podredumbre blanca es una enfermedad causada por uno de los hongos más polífagos, que posee la capacidad de atacar a muchos cultivos distintos, desde hortícolas y ornamentales hasta cultivos extensivos como girasol y soja. Es una de las podredumbres más agresivas del zucchini. Este patógeno no requiere heridas para penetrar en el hospedante y producir la enfermedad pudiendo pasar fácilmente de las raíces enfermas a las sanas.

.

Síntomas

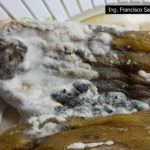

Los primeros síntomas ocasionado por Sclerotinia sclerotiorum se observan como lesiones con tejidos blandos y acuosos que no liberan mal olor. Si la humedad relativa es elevada, los zucchinis se cubren de un micelio blanco, algodonoso y abundante. Sobre el micelio pueden observarse esclerocios, blancos al principio y negros con el paso del tiempo, grandes, de forma irregular pudiendo llegar a cubrir por completo la zucchini.

Las plantas se marchitan y el tejido afectado cerca de la línea del suelo se empapa de agua. Un crecimiento blanco algodonoso profuso (micelio) puede observarse en las lesiones que se extienden rápidamente. Los cuerpos negros (esclerocios) se producen más tarde en las lesiones.

En el almacenamiento, la enfermedad se llama pudrición blanda acuosa.

.

Esquema del ciclo de vida del patógeno

Las especies de Sclerotinia spp. no se reproducen en forma asexual (no forman conidios).

.

Condiciones predisponentes

90 – 95 % humedad relativa y temperaturas entre 20ºC y 23ºC.

.

- 01 Síntomas y signo de la podredumbre blanca del zucchini causada por Sclerotinia sclerotiorum

- 02 Síntomas y signo de la podredumbre blanca del zucchini causada por Sclerotinia sclerotiorum

- 03 Síntomas y signo de la podredumbre blanca del zucchini causada por Sclerotinia sclerotiorum

- 04 Síntomas y signo de la podredumbre blanca del zucchini causada por Sclerotinia sclerotiorum

- 05 Síntomas y signo de la podredumbre blanca del zucchini causada por Sclerotinia sclerotiorum

- 06 Síntomas y signo de la podredumbre blanca del zucchini causada por Sclerotinia sclerotiorum

- 07 Síntomas y signo de la podredumbre blanca del zucchini causada por Sclerotinia sclerotiorum

- 08 Síntomas y signo de la podredumbre blanca del zucchini causada por Sclerotinia sclerotiorum

- 09 Síntomas y signo de la podredumbre blanca del zucchini causada por Sclerotinia sclerotiorum

- 10 Síntomas y signo de la podredumbre blanca del zucchini causada por Sclerotinia sclerotiorum

- 11 Síntomas y signo de la podredumbre blanca del zucchini causada por Sclerotinia sclerotiorum

.

Epidemiologia

El hongo puede sobrevivir a campo en el suelo como esclerocios, y también en los lugares de almacenamiento, además de sobrevivir saprofíticamente en frutos y hortalizas cosechadas.

El ciclo de la enfermedad comienza a partir de esclerocios, que reposan en el suelo, procedentes de infecciones anteriores. Los esclerocios bajo condiciones de humedad relativa alta y temperaturas medias, produciendo un número variable de apotecios. El apotecio cuando está maduro descarga numerosas ascoesporas, las que infectan principalmente los pétalos. Cuando se depositan sobre tallos, ramas u hojas producen infecciones secundarias.

.

Manejo de la enfermedad

* Solarización del suelo

* Rotaciones con cultivos no susceptibles (evitar la papa en la rotación)

* Arar en forma profunda para enterrar restos vegetales poco después de la cosecha si fuera posible.

* Evite el riego por aspersión o el riego excesivo usando una línea de goteo.

* Evitar el exceso de nitrógeno en los abonos

* Eliminar malezas

* Espaciar plantas y filas para promover el secado rápido.

.

.

.

Bibliografía

Albert D, Dumonceaux T, Carisse O, et al. (2022) Combining Desirable Traits for a Good Biocontrol Strategy against Sclerotinia sclerotiorum. Microorganisms 10(6): 1189. doi: 10.3390/microorganisms10061189

Amselem J, Cuomo CA, van Kan JAL, et al. (2011) Genomic analysis of the necrotrophic fungal pathogens Sclerotinia sclerotiorum and Botrytis cinerea. PLoS Genetics 7, e1002230. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002230

Boland GJ, Hall R (1994) Index of plant hosts of Sclerotinia sclerotiorum. Canadian Journal of Plant Pathology 16: 93-108. doi: 10.1080/07060669409500766

Bolton MD, Thomma BPHJ, Nelson BD (2006) Sclerotinia sclerotiorum (Lib.) de Bary: biology and molecular traits of a cosmopolitan pathogen. Molecular Plant Pathology 7: 1-16. doi: 10.1111/j.1364-3703.2005.00316.x

Cao Y, Zhang X, Song X, et al. (2024) Efficacy and toxic action of the natural product natamycin against Sclerotinia sclerotiorum. Pest Manag Sci. 10.1002/ps.7930

Dean R, Van Kan JAL, Pretorius ZA, et al. (2012) The Top 10 fungal pathogens in molecular plant pathology. Molecular Plant Pathology 13: 414–430. doi: 10.1111/j.1364-3703.2011.00783.x

, , (2022) The evolutionary and molecular features of the broad-host-range plant pathogen Sclerotinia sclerotiorum. Molecular Plant Pathology 00: 1– 16. doi: 10.1111/mpp.13221

El-Ashmony RMS, Zaghloul NSS, Milošević M, et al. (2022) The Biogenically Efficient Synthesis of Silver Nanoparticles Using the Fungus Trichoderma harzianum and Their Antifungal Efficacy against Sclerotinia sclerotiorum and Sclerotium rolfsii. Journal of Fungi. 8(6): 597. doi: 10.3390/jof8060597

Gambhir N, Kamvar ZN, Higgins R, et al. (2020) Spontaneous and Fungicide-Induced Genomic Variation in Sclerotinia sclerotiorum. Phytopathology. doi: 10.1094/PHYTO-10-20-0471-FI

Garg H, Li H, Sivasithamparam K, Barbetti MJ (2013) Differentially Expressed Proteins and Associated Histological and Disease Progression Changes in Cotyledon Tissue of a Resistant and Susceptible Genotype of Brassica napus Infected with Sclerotinia sclerotiorum. PLoS ONE 8(6): e65205. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0065205

Hossain MM, Sultana F, Rubayet MT, et al. (2025) White Mold: A Global Threat to Crops and Key Strategies for Its Sustainable Management. Microorganisms 13(1): 4. doi: 10.3390/microorganisms13010004

, , , Genome‐wide alternative splicing profiling in the fungal plant pathogen Sclerotinia sclerotiorum during the colonization of diverse host families. Mol Plant Pathology 22: 31– 47. doi: 10.1111/mpp.13006

Kamal MM, Savocchia S, Lindbeck KD, et al. (2016) Biology and biocontrol of Sclerotinia sclerotiorum (Lib.) de Bary in oilseed Brassicas. Australasian Plant Pathol. 45: 1–14. doi: 10.1007/s13313-015-0391-2

Liang X, Rollins JA (2018) Mechanisms of Broad Host Range Necrotrophic Pathogenesis in Sclerotinia sclerotiorum. Phytopathology 108(10): 1128-1140. doi: 10.1094/PHYTO-06-18-0197-RVW

Mbengue M, Navaud O, Peyraud R, et al. (2016) Emerging Trends in Molecular Interactions between Plants and the Broad Host Range Fungal Pathogens Botrytis cinerea and Sclerotinia sclerotiorum. Frontiers in Plant Science 7: 422. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2016.00422

Mei J, Ding Y, Li Y, et al. (2016) Transcriptomic comparison between Brassica oleracea and rice (Oryza sativa) reveals diverse modulations on cell death in response to Sclerotinia sclerotiorum. Sci Rep 6: 33706. doi: 10.1038/srep33706

Nicot PC, Avril F, Duffaud M, et al. (2018) Differential susceptibility to the mycoparasite Paraphaeosphaeria minitans among Sclerotinia sclerotiorum isolates. Tropical Plant Pathology 1–12. doi: 10.1007/s40858-018-0256-7

O’Sullivan CA, Belt K, Thatcher LF (2021) Tackling Control of a Cosmopolitan Phytopathogen: Sclerotinia. Front. Plant Sci. 12: 707509. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2021.707509

(1979) Sclerotinia sclerotiorum: history, diseases and symptomatology, host range, geographic distribution, and impact. Phytopathology 69: 875–880. doi: 10.1094/Phyto-69-875

(2022) Predicting field diseases caused by Sclerotinia sclerotiorum: A review. Plant Pathology 00: 1– 16. doi: 10.1111/ppa.13643

Saharan GS, Mehta N (2008) Sclerotinia Diseases of Crop Plants: Biology, Ecology and Disease Management. Springer, Dordrecht. 485 p. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4020-8408-9

, , , et al (2024) The schizotrophic lifestyle of Sclerotinia sclerotiorum. Molecular Plant Pathology 25: e13423. doi: 10.1111/mpp.13423

Singh M, Avtar R, Lakra N, et al. (2021) Genetic and Proteomic Basis of Sclerotinia Stem Rot Resistance in Indian Mustard [Brassica juncea (L.) Czern & Coss.]. Genes 12(11): 1784. doi: 10.3390/genes12111784

Smolińska U, Kowalska B (2018) Biological control of the soil-borne fungal pathogen Sclerotinia sclerotiorum – a review. J Plant Pathol 100: 1–12. doi: 10.1007/s42161-018-0023-0

Snowden AL (2008) Post-Harvest Diseases and Disorders of Fruits and Vegetables: Volume 1: General Introduction and Fruits. CRC Press, 1st Edition, 320 p. ISBN 9781840765977

Taylor A, Coventry E, Handy C, et al. (2018) Inoculum potential of Sclerotinia sclerotiorum sclerotia depends on isolate and host plant. Plant Pathology (in press). doi: 10.1111/ppa.12843

Trazilbo PJJ, Vieira RF, Teixeira H, Carneiro JES (2009) Foliar application of calcium chloride and calcium silicate decreases white mold intensity on dry beans. Tropical Plant Pathology 34(3): 171-174. doi: 10.1590/S1982-56762009000300006

Wei W, Xu L, Peng H, et al. (2022) A fungal extracellular effector inactivates plant polygalacturonase-inhibiting protein. Nat Commun 13: 2213. doi: 10.1038/s41467-022-29788-2

Xu L, Li G, Jiang D, Chen W (2018) Sclerotinia sclerotiorum: An Evaluation of Virulence Theories. Annual Review of Phytopathology 56: 311-338. doi: 10.1146/annurev-phyto-080417-050052

Zeng W, Wang D, Kirk W, Hao J (2012) Use of Coniothyrium minitans and other microorganisms for reducing Sclerotinia sclerotiorum. Biol Control 60: 225–232. doi: 10.1016/j.biocontrol.2011.10.009