.

Condición fitosanitaria: Presente

Grupo de cultivos: Hortícola

Especie hospedante: Papa (Solanum tuberosum)

Rango de hospedantes: A menudo se asocia con sus dos hospedantes más comunes, la papa y el tomate. Sin embargo, P. infestans tiene un amplio rango de hospedantes que incluye muchos miembros de las Solanaceae, como por ejemplo Solanum muricatum (Huo et al., 2023). Las solanáceas ornamentales también pueden ser hospedantes, como por ejemplo Petunia spp., Calibrachoa spp., así como las especies silvestres Solanum dulcamara, Solanum sarrachoides, etc.

Epidemiología: policíclica, aguda.

Etiología: Pseudohongo. Hemibiotrófico

Agente causal: Phytophthora infestans (Mont.) de Bary

Taxonomía: Eukaryota > Stramenopiles > Oomycetes > Peronosporales > Phytophthora

.

En Argentina, Lucca et al. genotipificaron aislamientos argentinos de P. infestans mediante PCR con una reacción multiplexada de 12 marcadores moleculares microsatélites (SSR) siguiendo la metodología propuesta por Li et al. (2013), que se complementó con el muestreo en campo con tarjetas FTA. Estos estudios determinaron que desde 2007, la población argentina del patógeno está dominada por la línea clonal EU_2_A1, diferente a la reportada a finales de los 90 (Forbes et al., 1998).

.

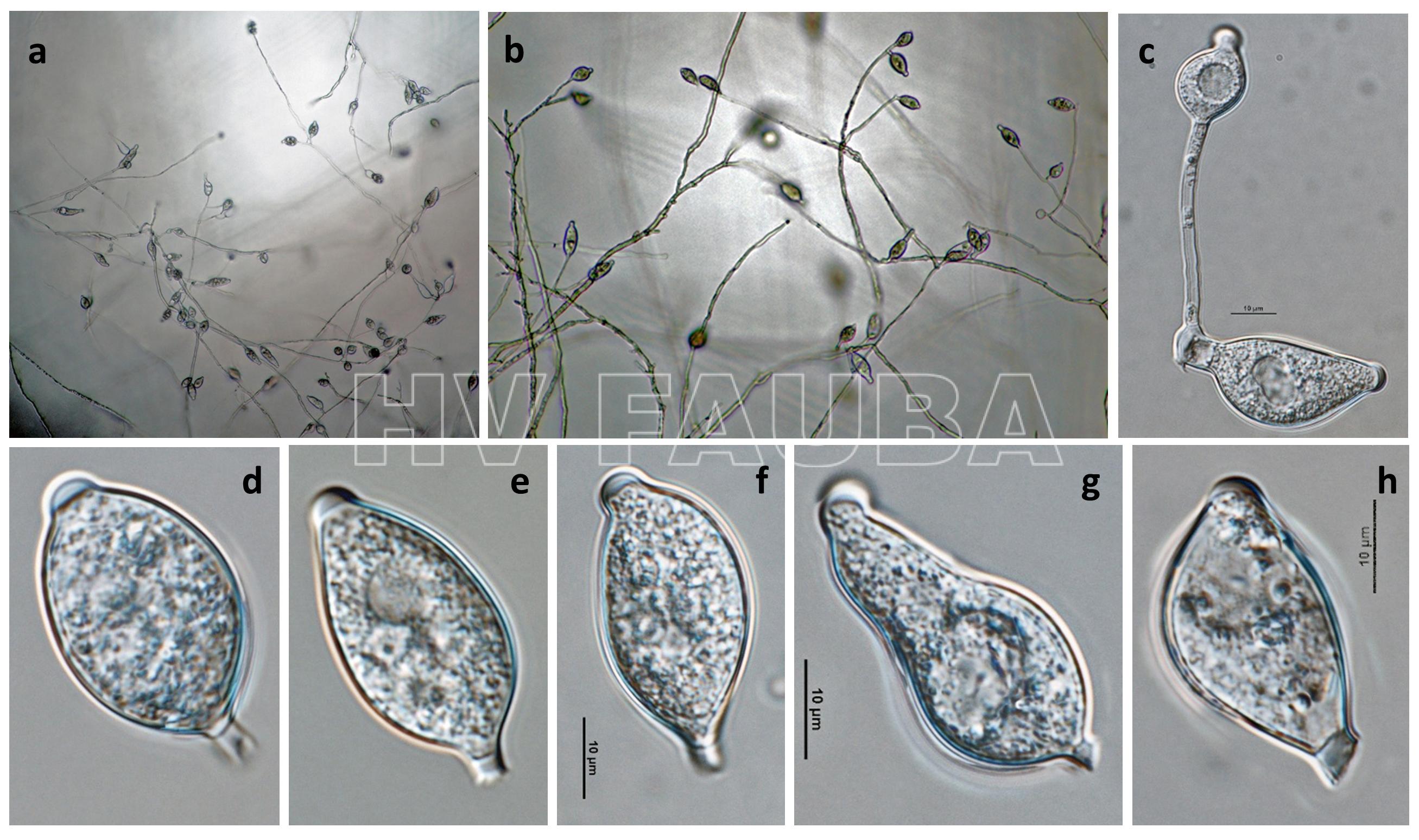

- Phytophthora infestans (fase asexual): (a, b) esporangios en esporangióforos; (c) germinación externa de esporangio; (d – h) esporangios papilados con pedicelos cortos y caducos. Autor: Gloria Abad, USDA-APHIS.

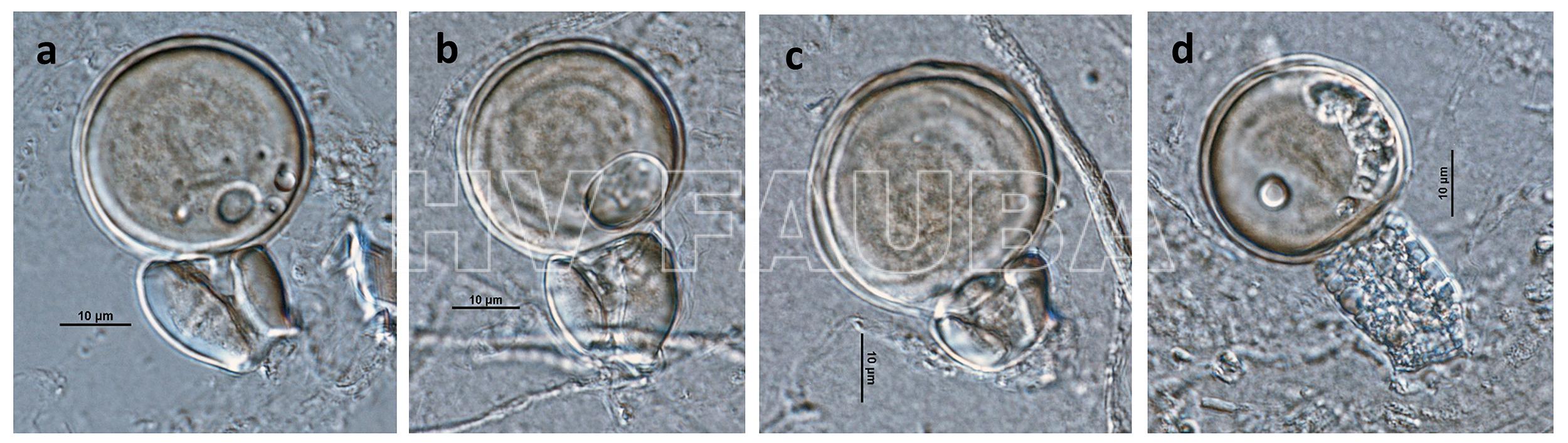

- Phytophthora infestans (fase sexual heterotálica A1 x A2): (a – d) oogonio de paredes lisas con anteridios anfiginosos y oosporas pleróticas. Autor: Gloria Abad USDA-APHIS-PPQ.

.

.

Antecedentes

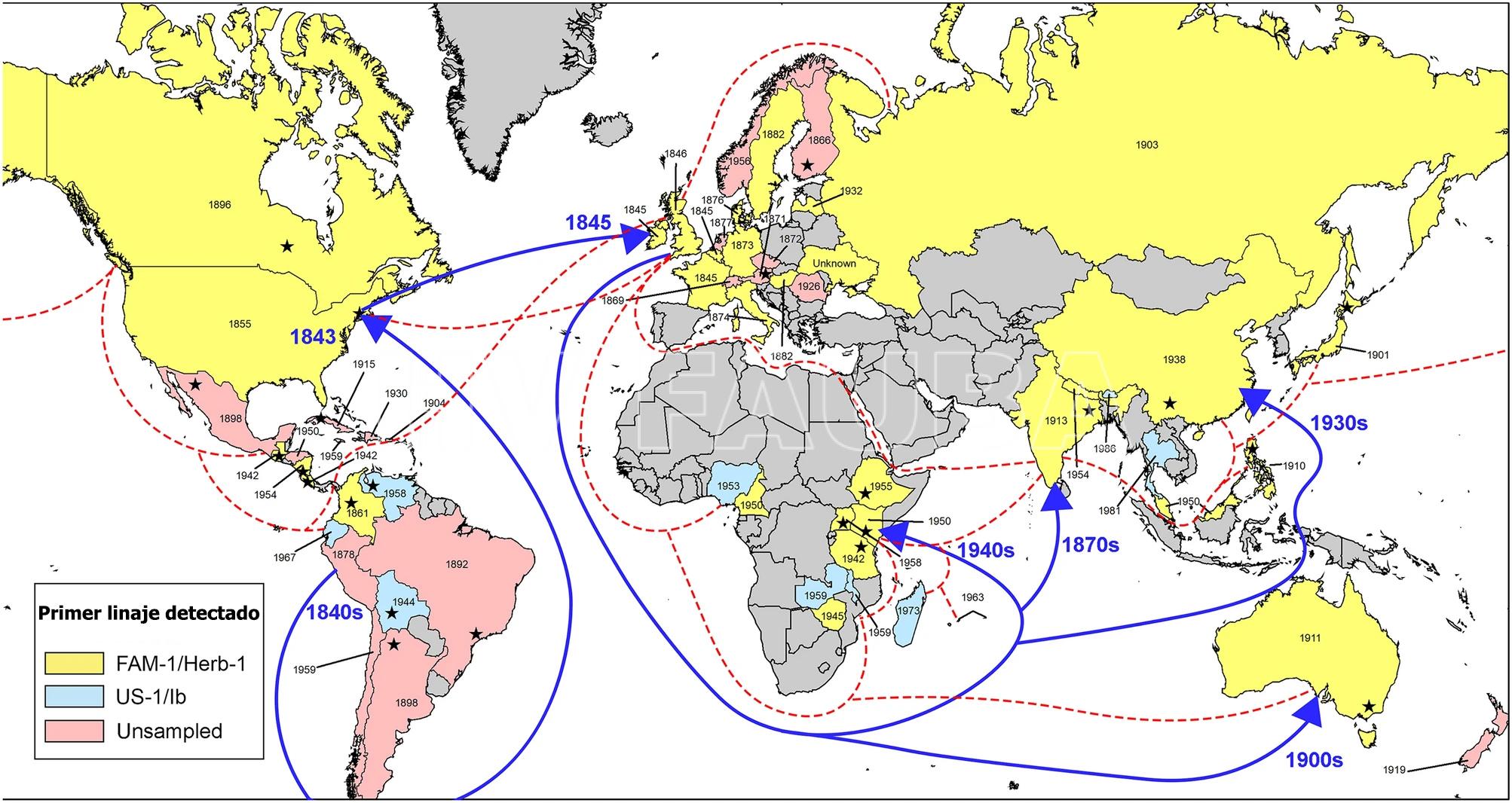

La enfermedad apareció por primera vez en los EE. UU. en 1843, cerca de los puertos de Nueva York, Filadelfia y los estados circundantes. La enfermedad se informó ampliamente por primera vez en el continente europeo dos años más tarde en Bélgica en 1845, después de lo cual se extendió por toda Europa y luego a Irlanda (Cox y Large, 1960; Bourke 1964; Zadoks, 2008; Ristaino et al., 2020). El linaje clonal que causó la hambruna de la papa en Irlanda (conocida mundialmente como «Gran hambruna irlandesa«) se denominó FAM-1, se secuenció el genoma y se documentó su ascendencia compartida con P. andina, una especie hermana de América del Sur (Martin et al., 2013). La ascendencia compartida de P. andina y el linaje de la hambruna sugieren que ambas especies pueden haber sido simpátricas en América del Sur (Martin et al., 2016).

.

- Mapa mundial de las primeras epidemias detectadas de tizón tardío causado por Phytophthora infestans. Los años dentro de cada país indican la fecha del espécimen más antiguo conocido, mientras que el color indica si el genotipo era FAM-1, US-1 o no muestreado. Las líneas punteadas indican rutas comerciales representativas del Imperio Británico alrededor de 1932. Las flechas indican la ruta de migración más probable tomada por el linaje FAM-1 hacia África y Asia y las rutas comerciales. Las estrellas dentro de cada país indican la ubicación aproximada del primer brote registrado, si se conoce. Autor: Saville y Ristaino, 2021.

.

.

Sintomatología

Se caracteriza por la presencia de manchas oscuras, que se inician por lo general en el borde o ápice de los folíolos. Si las condiciones ambientales son favorables para el desarrollo de la enfermedad, es posible observar en el envés de las hojas la presencia de una felpilla blanco grisáceo (signo de la enfermedad) constituida por micelio y zoosporangios del patógeno. En estas condiciones, las manchas progresan rápidamente, afectan los pecíolos y se produce defoliación (principalmente de las hojas inferiores).

En los tallos se observan manchas oscuras y alargadas. Al confluir éstas, el tallo queda totalmente ennegrecido, adquiere consistencia vítrea y se quiebra con facilidad.

El patógeno puede infectar a los tubérculos a través de yemas, lenticelas o heridas y también puede penetrar directamente la cutícula a través de apresorios (Resjö et al., 2017). Las zoosporas se enquistan y forman tubos germinativos que se hinchan hasta convertirse en apresorios (Grenville-Briggs et al., 2005). Se forma una clavija de infección y el patógeno infecta la planta por penetración directa a través de las células epidérmicas o de los estomas. La corteza de los tubérculos afectados toma una coloración castaño azulado, que pude abarcar parte o la totalidad de la superficie. Luego la infección se interna en el parénquima amiláceo, el que toma un color castaño muy característico que origina la denominación “papa chocolate” con la que se conoce la sintomatología. La podredumbre del tubérculo -en un comienzo seca- se transforma en húmeda, si se dan las condiciones, por la acción de agentes secundarios, especialmente bacterias, que se encuentran en el suelo.

.

- Autor: Saville et al., 2021

- Folíolo de papa infectado por tizón tardío causada por Phytophthora infestans. Se observa el sigo de la enfermedad, mildew, formado por los zoosporangios que salen al exterior del envés de la hoja por los estomas. Autor: Howard F. Schwartz, Colorado State University, United States.

- Autor: Maria A. Kuznetsova (All-Russian Research Institute of Phytopathology), EPPO.

- Autor: Cornell University

- Fuente: https://gd.eppo.int/taxon/PHYTIN

.

.

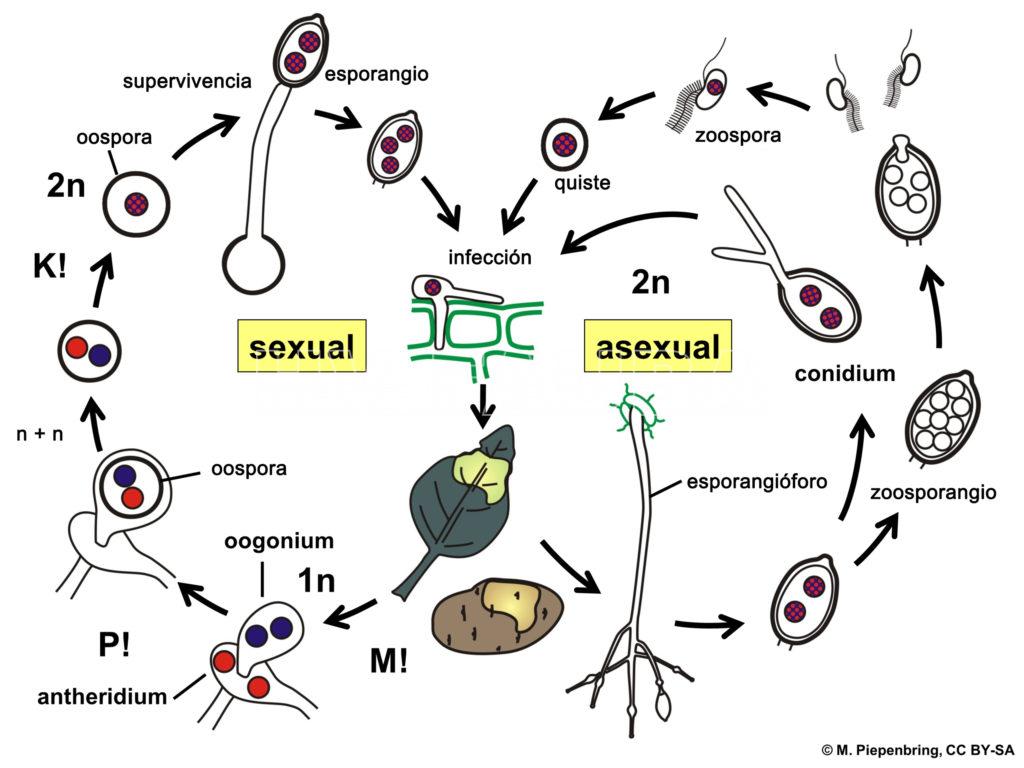

Patogénesis

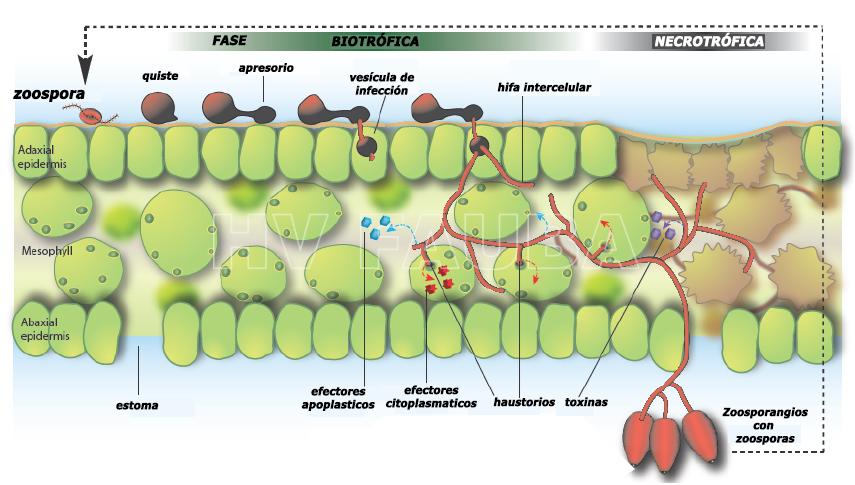

En la mayoría de los oomicetes parásitos de plantas, la infección generalmente comienza cuando las zoosporas móviles se enquistan y germinan en las superficies vegetales. Los esporangios también pueden iniciar infecciones. Los tubos germinativos forman un apresorio seguido de una clavija de penetración que perfora la cutícula. En algunas especies, como P. infestans, la clavija de penetración penetra en las células epidérmicas donde establece una vesícula de infección. Las especies de Phytophthora son patógenos hemibiotróficos, lo que significa que normalmente adoptan un proceso de infección de dos pasos: una fase temprana de infección «biotrófica» seguida de una necrosis extensa del tejido del hospedante asociada con crecimiento adicional y esporulación. Los patógenos de plantas de oomicetes típicamente establecen asociaciones íntimas con su hospedante vegetal. La colonización parasitaria es posible solo si se altera la fisiología del hospedante y se suprime la inmunidad de la planta (van Damme et al., 2011). Las hifas ramificadas, con estructuras similares a dígitos angostos conocidas como haustorios que invaginan las células del hospedante, se expanden desde el sitio de penetración hacia las células vecinas a través del espacio intercelular. Los haustorios se han relacionado con la introducción de proteínas efectoras dentro de las células vegetales y también puede funcionar en la absorción de nutrientes. Posteriormente, el tejido infectado se necrotiza y el micelio desarrolla zoosporangióforos que emergen a través de los estomas de las hojas o de la superficie de la raíz para producir asexualmente zoosporangios y completar el ciclo de vida.

Las proteínas similares al péptido 1 inductoras de necrosis y etileno (NLP = Necrosis and ethylene-inducing peptide 1–like proteins) son citolíticas y causan muerte celular y necrosis tisular al alterar la membrana plasmática de la planta. Las NLP son los únicos efectores de patógenos citolíticos conocidos que pueden permeabilizar las membranas plasmáticas de las plantas eudicotiledóneas. Recientemente, se identificaron los principales constituyentes de las membranas vegetales, las glicosilinositol fosforilceramidas (GIPC), como objetivos de la unión de la NLP a las membranas plasmáticas de las plantas. Las NLPs se secretan en el apoplasto, el espacio intersticial entre las células vegetales, donde la fuerza iónica es generalmente baja y las variaciones en la concentración de sal pueden afectar los procesos moleculares en la membrana plasmática de la planta. La NLP induce la formación de poros transitorios permeables a moléculas pequeñas. Este es el modo de acción molecular del daño de la membrana para un miembro de una gran familia de efectores de virulencia de este patógeno vegetal. El tamaño relativamente pequeño de las rupturas de la membrana indica que la actividad citotóxica de las NLP puede proporcionar a los patógenos iones y nutrientes de pequeño peso molecular derivados de células vegetales dañadas, mejorando así la virulencia de los patógenos necrotróficos. Esta alteración de la membrana es un proceso de varios pasos que incluye el reconocimiento de lípidos específicos de la planta impulsado electrostáticamente, unión superficial a la membrana, agregación de proteínas y formación transitoria de poros. El daño inducido por la NLP no es causado por una reorganización de la membrana ni por defectos a gran escala, sino por pequeñas roturas de la membrana. Este mecanismo distinto de alteración de la membrana lipídica está altamente adaptado para dañar eficazmente las células vegetales (Pirc et al., 2022).

.

- Ciclo de infección hemibiotrófico de Phytophthora infestans. Autor: van Damme et al., 2011

.

.

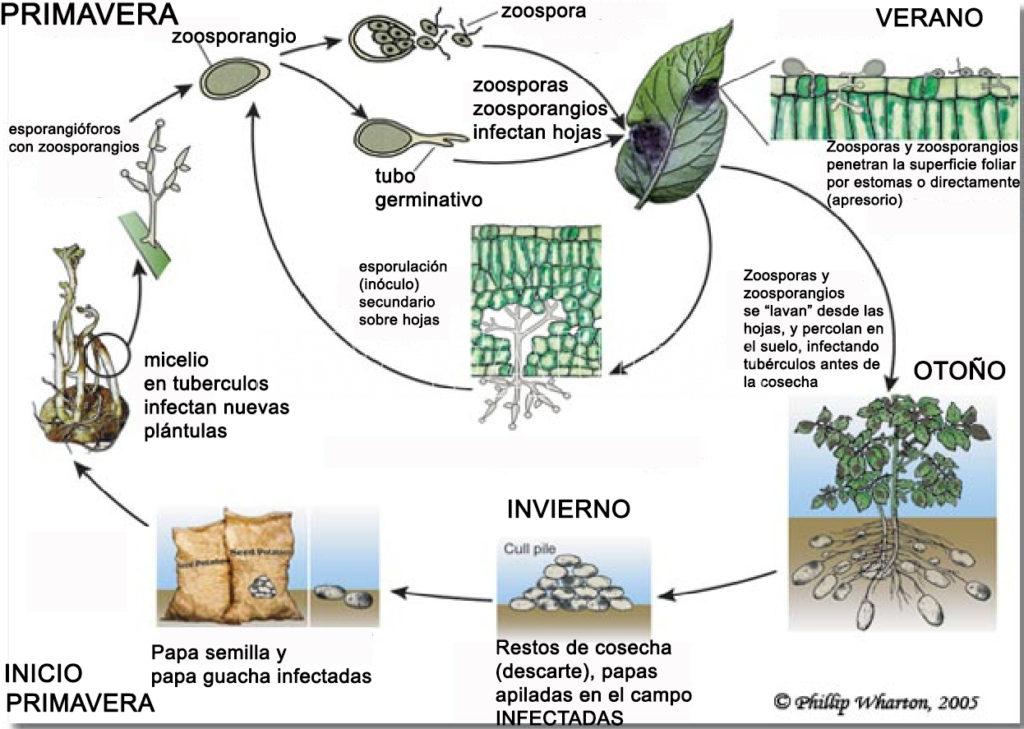

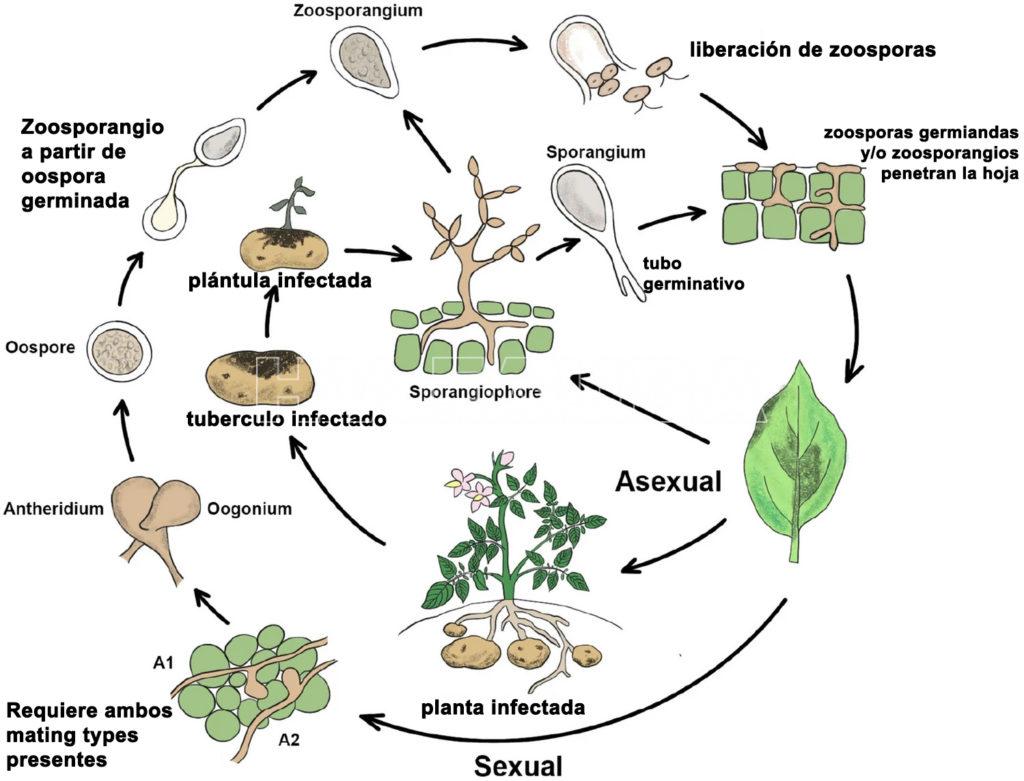

Ciclo de la enfermedad

En Argentina, P. infestans se perpetúa en los tubérculos infectados que permanecen en el suelo o en el almacenamiento. En países donde existe el ciclo sexual, este estado tiene importancia, pero en las que se producen cigotas por partenogénesis, no la tiene. En Argentina, lo más aceptado actualmente es que el pseudohongo sobrevive: 1) como micelio en tubérculos afectados que han quedado en el suelo; 2) en las pilas de papas desechadas o basurales; y 3) las “papa semilla” infectadas que se emplean en el momento de la plantación.

Hay dos etapas de infección:

a) A partir de las tres fuentes de inóculo anteriormente citadas, el pseudohongo desarrolla en el tejido que brota de las papas y esporula en la parte aérea de la planta. En el tallo invade rápidamente la región cortical causando clorosis y colapso de las células. Luego desarrolla entre las células de la médula del tallo, pero es raro encontrarlo en el sistema vascular. El micelio invade los brotes y acompaña su crecimiento a través del suelo y sobre la superficie del mismo. Al alcanzar la parte aérea de la planta de papa, esporula produciendo zoosporangios que emergen por los estomas de tallos y hojas y son proyectados al aire. Una vez maduro el esporangio se desprende y es llevado por el viento o dispersado por la lluvia. Cuando los zoosporangios se depositan sobre hojas o tallos húmedos germinan y a través de un tubo germinativo de zoosporas producen la reinfección. El tubo germinativo de una zoopora o de un zoosporangio penetra por la cutícula o por estomas y produce micelio, que crece profusamente entre las células y emite haustorios largos, curvados. Las células en las que el micelio se alimenta mueren y cuando comienzan a decaer el micelio se difunde por la periferia en los tejidos nuevos. Poco día después los nuevos zoosporangióforos son difundidos por el viento infectando nuevas plantas. En condiciones favorables, el tiempo desde infección hasta formación de zoosporangios es de 4 días o menos. Se producen un gran número de generaciones asexuales y nuevas infecciones en una estación. Con el avance de la infección las lesiones crecen y aparecen nuevas, lo que determina la muerte del follaje y la reducción proporcional en el rendimiento.

b) Infección de los tubérculos: ocurre en el campo cuando con tiempo húmedo los zoosporangios son llevados de las hojas hacia abajo, llegan al suelo llevados por las gotas de lluvia y se infiltran hasta alcanzar la superficie del tubérculo de papa. Los tubérculos cercanos a la superficie del suelo son atacados por las zoosporas que germinan y penetran por lenticelas o heridas. En el tubérculo el micelio crece principalmente entre las células y produce largos haustorios con forma de hoz que penetran las células. Estos órganos subterráneos rara vez son infectados por el micelio que crece en el tallo de una planta madre enferma. Sin embargo, en la cosecha los tubérculos se contaminan con los zoosporangios viables presentes en el suelo o en follaje enfermo aun verde ó, si los tubérculos están expuestos mientras el pseudohongo está esporulando, esta infección se desarrollará durante el almacenaje.

Los zoosporangios de este patógeno son diseminados por el viento y dan lugar a zoosporas móviles que, si hay disponibilidad de agua líquida en la superficie del tejido, penetran a través de los estomas. A temperaturas más elevadas los zoosporangios pueden germinar con un tubo germinativo, sin la intervención de zoosporas. En condiciones favorables, a los pocos días de incubación se forman las lesiones típicas con abundante esporulación. En condiciones controladas de laboratorio se estimó un período de incubación de 2 días y pico (menor a 3 días), por lo que se puede considerar una enfermedad aguda (Lebecka y Sobkowiak, 2013). De esta manera, la epidemia avanza muy rápidamente. Para que esto ocurra debe haber períodos prolongados de alta humedad y temperaturas frescas. Temperaturas mayores de los 30°C interrumpen el avance de la epidemia.

El pseudohongo «inverna» en forma de micelio, en tubérculos de plantas voluntarias, en tubérculos desechados que se apilan o en los tubérculos infectados que se almacenan. Luego de la emergencia de las plantas, el pseudohongo invade brotes en desarrollo y esporula si las condiciones de humedad son favorables. Una vez producida la infección primaria, la diseminación de la enfermedad (infecciones secundarias) se realiza por medio de los zoosporangios transportados por el agua o el viento.

.

.

- Ciclo biológico-agronómico del Tizón tardío de la papa, causado por Phytophthora infestans. Autor: Phillip Wharton, 2005.

- Ciclo del tizón tardío de la papa (P. infestans) en países donde existe el ciclo sexual. Autor: Jayawardena et al., 2020.

- Esquema del ciclo de vida de Phytophthora infestans. Autor: Piepenbring M.

.

Condiciones predisponentes

Se manifiesta con tiempo lluvioso, alta humedad y bajas temperaturas. En la Argentina se ha observado que las epidemias de tizón tardío se producen en años de lluvias abundantes. Cuando se registran mañanas frescas (13ºC a 18ºC) sucesivas, acompañadas de abundante rocío y neblinas, seguidas de calor húmedo, las probabilidades de infección son muy altas.

.

Medidas de manejo Integrado

* Variedades resistentes: si bien los grupos de investigadores de nuestro país están trabajando en la obtención de variedades resistentes, éstas todavía no están disponibles. Existen variedades tolerantes como Innovator (variedad de papa para industria).

* Eliminación de fuentes de inóculo primario (pilas de descarte, papa guacha). Para evitar la proliferación de la enfermedad en la etapa de poscosecha no deberán almacenarse papas que provengan de cultivos con ataques severos.

* Aplicación de oomyceticidas cuando las condiciones ambientales lo indiquen: al ser una enfermedad estrechamente ligada a los altos niveles de humedad relativa y a las precipitaciones acumuladas, los sistemas de alarma son efectivos cuando están ajustados. Si no se contara con este tipo de herramienta, las aplicaciones se harán según calendario debiendo efectuarse frecuentemente y a períodos cortos. Actualmente se dispone en Argentina de la posibilidad de poder contratar el servicio pago de Phytoalert®– Convenio entre INTA, Universidad de Wageningen (Holanda) y McCain Argentina; el cual es un Sistema de Apoyo para la Toma de Decisiones o DSS (siglas del inglés: Decision Support System) juega un papel fundamental en el uso racional de fungicidas. En otros países se han desarrollado otros modelos de predicción de riesgo de tizón para guiar las aplicaciones de fitosanitarios (Cucak et al. 2019, 2020; Hansen et al., 2017; Dowley et al., 2004).

.

- Tizón tardío (Phytophthora infestans). Lesión temprana en hoja

- 01 Síntomas foliares típicos del tizón tardío de la papa causado por Phytophthora infestans. 5 dpi (días post inoculación) en plantas de papa variedad Spunta con de 45 días de edad.

- 02 Síntomas foliares típicos del tizón tardío de la papa causado por Phytophthora infestans. 5 dpi (días post inoculación) en plantas de papa variedad Spunta con de 45 días de edad.

- 03 Síntomas foliares típicos del tizón tardío de la papa causado por Phytophthora infestans. 5 dpi (días post inoculación) en plantas de papa variedad Spunta con de 45 días de edad.

- 04 Síntomas foliares típicos del tizón tardío de la papa causado por Phytophthora infestans. 5 dpi (días post inoculación) en plantas de papa variedad Spunta con de 45 días de edad.

- 05 Síntomas foliares típicos del tizón tardío de la papa causado por Phytophthora infestans. 5 dpi (días post inoculación) en plantas de papa variedad Spunta con de 45 días de edad.

- 06 Síntomas foliares típicos del tizón tardío de la papa causado por Phytophthora infestans. 5 dpi (días post inoculación) en plantas de papa variedad Spunta con de 45 días de edad.

- 07 Síntomas foliares típicos del tizón tardío de la papa causado por Phytophthora infestans. 5 dpi (días post inoculación) en plantas de papa variedad Spunta con de 45 días de edad.

- 08 Síntomas foliares típicos del tizón tardío de la papa causado por Phytophthora infestans. 5 dpi (días post inoculación) en plantas de papa variedad Spunta con de 45 días de edad.

- 09 Síntomas foliares típicos del tizón tardío de la papa causado por Phytophthora infestans. 5 dpi (días post inoculación) en plantas de papa variedad Spunta con de 45 días de edad.

- 10 Síntomas foliares típicos del tizón tardío de la papa causado por Phytophthora infestans. 5 dpi (días post inoculación) en plantas de papa variedad Spunta con de 45 días de edad.

- 11 Síntomas foliares típicos del tizón tardío de la papa causado por Phytophthora infestans. 5 dpi (días post inoculación) en plantas de papa variedad Spunta con de 45 días de edad.

- 12 Síntomas foliares típicos del tizón tardío de la papa causado por Phytophthora infestans. 5 dpi (días post inoculación) en plantas de papa variedad Spunta con de 45 días de edad.

- 13 Síntomas foliares típicos del tizón tardío de la papa causado por Phytophthora infestans. 5 dpi (días post inoculación) en plantas de papa variedad Spunta con de 45 días de edad.

- 14 Zoosporangio de P. infestans liberando zoosporas. Autor: Dra. Elisa Frantino

.

.

.

Videos

WPC Webinar #17 – Phytophthora Infestans: Late Blight

Zoospore Infection – Phytophthora nicotianae

Identificando y Explorando para el Tizón Tardío en su Campo (español)

Tizón Tardio. INIA

.

.

Bibliografía

Tizón Latino. Red latinoamericana de cooperación para el estudio del tizón tardío de las solanáceas.

Federación Nacional de Productores de Papa

Abad ZG, Burgess T, Redford AJ, et al. (2022) IDphy: An international online resource for molecular and morphological identification of Phytophthora. Plant Disease. doi: 10.1094/PDIS-02-22-0448-FE

Abdelrahman O, Yagi S, El Siddig M, et al. (2022) Evaluating the Antagonistic Potential of Actinomycete Strains Isolated From Sudan’s Soils Against Phytophthora infestans. Front Microbiol. 13: 827824. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2022.827824

Abuley I, Hansen JG (2022) Characterisation of the level and type of resistance of potato varieties to late blight (Phytophthora infestans). Phytopathology. doi: 10.1094/PHYTO-07-21-0309-R

Abuley IK, Lynott JS, Hansen JG, et al. (2023) The EU43 genotype of Phytophthora infestans displays resistance to mandipropamid. Plant Pathology 00, 1– 9. doi: 10.1111/ppa.13737

Afanasenko OS, Khiutti AV, Mironenko NV, Lashina NM (2022) Transmission of potato spindle tuber viroid between Phytophthora infestans and host plants. Vavilovskii Zhurnal Genet Selektsii. 26(3): 272-280. doi: 10.18699/VJGB-22-34

Agho CA, Kaurilind E, Tähtjärv T, et al. (2023) Comparative transcriptome profiling of potato cultivars infected by late blight pathogen Phytophthora infestans: Diversity of quantitative and qualitative responses. Genomics:110678. doi: 10.1016/j.ygeno.2023.110678

Aguilera-Galvez C, Champouret N, Rietman H, et al. (2018) Two different R gene loci co-evolved with Avr2 of Phytophthora infestans and confer distinct resistance specificities in potato. Studies in Mycology 89:105-115. doi: 10.1016/j.simyco.2018.01.002

Ah-Fong AMV, Shrivastava J, Judelson HS (2017) Lifestyle, gene gain and loss, and transcriptional remodeling cause divergence in the transcriptomes of Phytophthora infestans and Pythium ultimum during potato tuber colonization. BMC Genomics 18: 764. doi: 10.1186/s12864-017-4151-2

, , , A Cas12a‐based gene editing system for Phytophthora infestans reveals monoallelic expression of an elicitor. Molecular Plant Pathology 00: 1– 16. doi: 10.1111/mpp.13051

Alfiky A, L’Haridon F, Abou-Mansour E, Weisskopf L (2022) Disease inhibiting effect of strain Bacillus subtilis EG21 and its metabolites against potato pathogens Phytophthora infestans and Rhizoctonia solani. Phytopathology. doi: 10.1094/PHYTO-12-21-0530-R

Alfiky A, Abou-Mansour E, de Vrieze M, et al. (2023) Newly isolated Trichoderma spp. show multifaceted biocontrol strategies to inhibit potato late blight causal agent Phytophthora infestans both in vitro and in planta. Phytobiomes Journal. doi: 10.1094/PBIOMES-01-23-0002-R

Armstrong MR, Vossen J, Lim TY, et al. (2018) Tracking disease resistance deployment in potato breeding by enrichment sequencing. bioRxiv 360644. doi: 10.1101/360644

Arseneault T, Pieterse CM, Gérin-Ouellet M, Goyer C, Filion M (2014) Long-term induction of defense gene expression in potato by pseudomonas sp. LBUM223 and streptomyces scabies. Phytopathology 104(9): 926-32. doi: 10.1094/PHYTO-11-13-0321-R

Aubel G, Serderidis S, Ivens J, et al. (2018) Oligosaccharides successfully thwart hijacking of the salicylic acid pathway by Phytophthora infestans in potato leaves. Plant Pathology. doi: 10.1111/ppa.12908

) Emergence of Potato Blight, 1843–46. Nature 203: 805–808. doi: 10.1038/203805a0

Avila-Quezada GD, Rai M (2023) Novel nanotechnological approaches for managing Phytophthora diseases of plants. Trends Plant Sci.: S1360-1385(23)00102-4. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2023.03.022

Avrova AO, Boevink PC, Young V, et al. (2008) A novel Phytophthora infestans haustorium-specific membrane protein is required for infection of potato. Cell Microbiology 10(11): 2271–2284. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2008.01206.x

Ayala-Usma DA, Cárdenas M, Guyot R, et al. (2021) A whole genome duplication drives the genome evolution of Phytophthora betacei, a closely related species to Phytophthora infestans. BMC Genomics 22(1): 795. doi: 10.1186/s12864-021-08079-y

Becktell MC, Daughtrey ML, Fry WE (2005) Temperature and Leaf Wetness Requirements for Pathogen Establishment, Incubation Period, and Sporulation of Phytophthora infestans on Petunia × hybrida. Plant Disease 89(9): 975-979. doi: 10.1094/PD-89-0975

Belisle RJ, Hao W, Riley N, et al. (2022) Root absorption and limited mobility of mandipropamid as compared to oxathiapiprolin and mefenoxam after soil treatment of citrus plants for managing Phytophthora root rot. Plant Dis. doi: 10.1094/PDIS-07-22-1699-RE

Beninal L, Bouznad Z, Corbière R, et al. (2021) Distribution of major clonal lineages EU_13_A2, EU_2_A1, and EU_23_A1 of Phytophthora infestans associated with potato late blight across crop seasons and regions in Algeria. Plant Pathology 00: 1– 12. doi: 10.1111/ppa.13471

Bentham AR, Wang W, Trusch F, et al. (2023) The WY domain of an RxLR effector drives interactions with a host target phosphatase to mimic host regulatory proteins and promote Phytophthora infestans infection. Mol Plant Microbe Interact. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-08-23-0118-FI

Bi W, Liu J, Li Y, et al. (2023) CRISPR/Cas9-guided editing of a novel susceptibility gene in potato improves Phytophthora

Biessy A, Novinscak A, St-Onge R, et al. (2021) Inhibition of Three Potato Pathogens by Phenazine-Producing Pseudomonas spp. Is Associated with Multiple Biocontrol-Related Traits. mSphere 6(3): e0042721. doi: 10.1128/mSphere.00427-21

Blackwell EM (1953) Haustoria of Phytophthora infestans and some other species. Transactions of the British Mycological Society 36: 138-158. doi: 10.1016/S0007-1536(53)80058-6

Borza T, Schofield A, Sakthivel G, et al. (2014) Ion chromatography analysis of phosphite uptake and translocation by potato plants: Dose-dependent uptake and inhibition of Phytophthora infestans development. Crop Protection 56: 74-81. doi: 10.1016/j.cropro.2013.10.024

Bourke PMA (1964) Emergence of potato blight, 1843–46. Nature 203: 805–808. doi: 10.1038/203805a0

Bradshaw MJ, Boufford D, Braun U, et al. (2024) An In-Depth Evaluation of Powdery Mildew Hosts Reveals One of the World’s Most Common and Widespread Groups of Fungal Plant Pathogens. Plant Dis. 108(3): 576-581. doi: 10.1094/PDIS-07-23-1471-RE

Brasier C, Scanu B, Cooke D, Jung T (2022) Phytophthora: an ancient, historic, biologically and structurally cohesive and evolutionarily successful generic concept in need of preservation. IMA Fungus 13(1): 12. doi: 10.1186/s43008-022-00097-z

Bronkhorst J, Kasteel M, van Veen S, et al. (2021) A slicing mechanism facilitates host entry by plant-pathogenic Phytophthora. Nat Microbiol 6: 1000–1006. doi: 10.1038/s41564-021-00919-7

Bronkhorst J, Kots K, de Jong D, et al. (2022) An actin mechanostat ensures hyphal tip sharpness in Phytophthora infestans to achieve host penetration. Sci Adv. 8(23): eabo0875. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.abo0875

, , , et al. (2020) Towards a best practice methodology for the detection of Phytophthora species in soils. Plant Pathology 00: 1– 11. doi: 10.1111/ppa.13312

Burgess TI, Edwards J, Drenth A, et al. (2021) Current status of Phytophthora in Australia. Persoonia 47: 151-177. doi: 10.3767/persoonia.2021.47.05

Burra DD, Berkowitz O, Hedley PE, et al. (2014) Phosphite-induced changes of the transcriptome and secretome in Solanum tuberosum leading to resistance against Phytophthora infestans. BMC Plant Biology 14: 254. doi: 10.1186/s12870-014-0254-y

Campbell AM, Moon RP, Duncan JM, et al. (1989) Protoplast formation and regeneration from sporangia and encysted zoospores of Phytophthora infestans. Physiol. Mol. Plant P. 34: 299–307. doi: 10.1016/0885-5765(89)90027-1

, , , (2021) A review of knowledge on the mechanisms of action of the rare sugar d-tagatose against phytopathogenic oomycetes. Plant Pathology 70: 1979– 1986. doi: 10.1111/ppa.13440

Champouret N, Bouwmeester K, Rietman H, et al. (2009) Phytophthora infestans isolates lacking class I ipiO variants are virulent on Rpi-blb1 potato. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 22: 1535–1545. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-22-12-1535

Chaves SC, Rodríguez MC, Mideros MF, et al. (2019) Determining Whether Geographic Origin and Potato Genotypes Shape the Population Structure of Phytophthora infestans in the Central Region of Colombia. Phytopathology 109(1): 145-154. doi: 10.1094/PHYTO-05-18-0157-R

Chaves SC, Guayazán N, Mideros MF, et al. (2020) Two Clonal Species of Phytophthora Associated to Solanaceous Crops Coexist in Central and Southern Colombia. Phytopathology 110(7): 1342-1351. doi: 10.1094/PHYTO-05-19-0175-R

Chen Y, Halterman DA (2017) Phytophthora infestans Effectors IPI-O1 and IPI-O4 Each Contribute to Pathogen Virulence. Phytopathology 107(5): 600-606. doi: 10.1094/PHYTO-06-16-0240-R

Chepsergon J, Motaung TE, Moleleki LN (2021) «Core» RxLR effectors in phytopathogenic oomycetes: A promising way to breeding for durable resistance in plants? Virulence 12(1): 1921-1935. doi: 10.1080/21505594.2021.1948277

Childers R, Danies G, Myers K, et al. (2015) Acquired resistance to mefenoxam in sensitive isolates of Phytophthora infestans. Phytopathology 105: 342-349. doi: 10.1094/PHYTO-05-14-0148-R

Coomber AL, Saville AC, Carbone I, et al. (2025) A pangenome analysis reveals the center of origin and evolutionary history of Phytophthora infestans and 1c clade species. PLoS ONE 20(1): e0314509. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0314509

Corneo PE, Nesler A, Lotti C, et al. (2021) Interactions of tagatose with the sugar metabolism are responsible for Phytophthora infestans growth inhibition. Microbiological Research 247: 126724. doi: 10.1016/j.micres.2021.126724

Corneo PE, Nesler A, Lotti C, et al. (2021) Corrigendum to “Interactions of tagatose with the sugar metabolism are responsible for Phytophthora infestans growth inhibition”. Microbiol. Res. 247: 126724. Microbiological Research 126827. doi: 10.1016/j.micres.2021.126827

Cox AE, Large EC (1960) Potato blight epidemics throughout the world. Agric. Handb. 174: 1–230. Link

(2019) Evaluation of the “Irish Rules”: The potato late blight forecasting model and its operational use in the Republic of Ireland. Agronomy (Basel) 9: 515. doi: 10.3390/agronomy9090515

Cucak M, de Andrade Moral R, Fealy R, et al. (2021) Opportunities for Improved Potato Late Blight Management in the Republic of Ireland: Field Evaluation of the Modified Irish Rules Crop Disease Risk Prediction Model. Phytopathology: PHYTO01200011R. doi: 10.1094/PHYTO-01-20-0011-R

Dagdas YF, Pandey P, Tumtas Y, et al. (2018) Host autophagy machinery is diverted to the pathogen interface to mediate focal defense responses against the Irish potato famine pathogen. Elife 7. pii: e37476. doi: 10.7554/eLife.37476

Deweer C, Sahmer K, Muchembled J (2023) Anti-oomycete activities from essential oils and their major compounds on Phytophthora infestans. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int. doi: 10.1007/s11356-023-29270-6

Dey T, Saville A, Myers K, et al. (2018) Large sub-clonal variation in Phytophthora infestans from recent severe late blight epidemics in India. Scientific Reportsvolume 8, Article number: 4429. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-22192-1

Doke N (1983) Involvement of superoxide anion generation in the hypersensitive response of potato tuber tissues to infection with an incompatible race of Phytophthora infestans and to the hyphal wall components. Physiological Plant Pathology 23(3): 345-357. doi: 10.1016/0048-4059(83)90019-X

Domazakis E, Wouters D, Visser R, et al. (2018) The ELR-SOBIR1 complex functions as a two-component RLK to mount defense against Phytophthora infestans. Molecular Plant-Microbe Interactions (Accepted for publication). doi: 10.1094/MPMI-09-17-0217-R

Dowley LJ, Burke JJ (2004) Field validation of four decision support systems for the control of late blight of potatoes in Ireland. Potato Res. 47: 151. doi: 10.1007/BF02735981

(2008) Yield losses caused by late blight (Phytophthora infestans (Mont.) de Bary) in potato crops in Ireland. Ir. J. Agric. Food Res. 47: 69-78. ISI

Duggan C, Moratto E, Savage Z, et al. (2021) Dynamic localization of a helper NLR at the plant–pathogen interface underpins pathogen recognition. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 118 (34): e2104997118. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2104997118

Dulal N, Wilson RA (2024) Paths of Least Resistance: Unconventional Effector Secretion by Fungal and Oomycete Plant Pathogens. Mol Plant Microbe Interact. 37(9): 653-661. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-12-23-0212-CR

Elnahal ASM, Li J, Wang X, et al. (2020) Identification of Natural Resistance Mediated by Recognition of Phytophthora infestans Effector Gene Avr3aEM in Potato. Front. Plant Sci. 11: 919. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2020.00919

Enciso-Rodriguez F, Douches D, Lopez-Cruz M, et al. (2018) Genomic Selection for Late Blight and Common Scab Resistance in Tetraploid Potato (Solanum tuberosum). G3 (Bethesda) 8(7): 2471-2481. doi: 10.1534/g3.118.200273

Fabro G (2021) Oomycete intracellular effectors: specialized weapons targeting strategic plant processes. New Phytol. doi: 10.1111/nph.17828

Fantino E, Segretin ME, Santin F, Mirkin FG, Ulloa RM (2017) Analysis of the potato calcium-dependent protein kinase family and characterization of StCDPK7, a member induced upon infection with Phytophthora infestans. Plant Cell Reports 36(7): 1137–1157. doi: 10.1007/s00299-017-2144-x

Feldman ML, Guzzo MC, Machinandiarena MF, et al. (2020) New insights into the molecular basis of induced resistance triggered by potassium phosphite in potato. Physiological and Molecular Plant Pathology, 109, 101452. doi: 10.1016/j.pmpp.2019.101452

Firester B, Shtienberg D, Blank L (2018) Modelling the spatiotemporal dynamics of Phytophthora infestans at a regional scale. Plant Pathology. doi: 10.1111/ppa.12860

Forbes GA, Grünwald NJ, Mizubuti ESG, et al. () Potato Late Blight in Developing Countries. Link

Forbes GA, Jarvis MC (1994) Host resistance for management of potato late blight. In: Zehnder G, Jansson R, Raman KV, eds. Advances in Potato Pest Biology and Management. St. Paul, Minnesota: American Phytopathological Society, 439-57.

Forbes GA, Escobar XC, Ayala CC, et al. (1997) Population genetic structure of Phytophthora infestans in Ecuador. Phytopathology 87: 375-80. doi: 10.1094/PHYTO.1997.87.4.375

Forbes GA, Goodwin SB, Drenth A, et al. (1998) A Global Marker Database for Phytophthora infestans. Plant Disease 82(7): 811-818. doi: 10.1094/PDIS.1998.82.7.811

Forbes GA, Chacón MG, Kirk HG, et al. (2005) Stability of resistance to Phytophthora infestans in potato: an international evaluation. Plant Pathology 54: 364-372. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3059.2005.01187.x

Forbes GA, Landeo JA (2006) Late Blight. In: Gopal J ,P. KSM, eds. Handbook of Potato Production, Improvement, and Postharvest Management. Binghamton, NY: Haworth Press Inc., 279-320.

Foster ZSL, Albornoz FE, Fieland VJ, et al. (2022) A New Oomycete Metabarcoding Method Using the rps10 Gene. Phytobiomes Journal 6: 214-226. doi: 10.1094/PBIOMES-02-22-0009-R

Fry WE, Apple AE, Bruhn JA (1983) Evaluation of potato late blight forecasts modified to incorporate host resistance and fungicide weathering. Phytopathology 73:1054-1059. doi: 10.1094/Phyto-73-1054

Gao et al. (2021) Comparative analysis of Phytophthora genomes reveals oomycete pathogenesis in crops. Heliyon 7: e06317. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2021.e06317

Gao RF, Wang JY, Liu KW, et al. (2021) Comparative analysis of Phytophthora genomes data. Data Brief. 39: 107663. doi: 10.1016/j.dib.2021.107663

Gevens AJ, Seidl AC (2013) First Report of Late Blight Caused by Phytophthora infestans Clonal Lineage US-23 on Tomato and Potato in Wisconsin, United States. Plant Disease 97(6): 839. doi: 10.1094/PDIS-09-12-0821-PDN

Gfeller A, Fuchsmann P, De Vrieze M, et al. (2022) Bacterial Volatiles Known to Inhibit Phytophthora infestans Are Emitted on Potato Leaves by Pseudomonas Strains. Microorganisms 10(8): 1510. doi: 10.3390/microorganisms10081510

Gilroy EM, Taylor RM, Hein I, et al. (2011) CMPG1-dependent cell death follows perception of diverse pathogen elicitors at the host plasma membrane and is suppressed by Phytophthora infestans RXLR effector AVR3a. New Phytol. 190(3): 653-66. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2011.03643.x

González-Tobón J, Childers R, Olave C, et al. (2020) Is the Phenomenon of Mefenoxam-Acquired Resistance in Phytophthora infestans Universal? Plant Disease 104(1): 211-221. doi: 10.1094/PDIS-10-18-1906-RE

González-Tobón J, Childers RR, Rodríguez A, et al. (2022) Searching for the Mechanism that Mediates Mefenoxam-Acquired Resistance in Phytophthora infestans and How It Is Regulated. Phytopathology 112(5): 1118-1133. doi: 10.1094/PHYTO-07-21-0280-R

Goodwin SB, Sujkowski LS, Dyer AT, et al. (1995) Direct detection of gene flow and probable sexual reproduction of Phytophthora infestans in northern North America. Phytopathology 85: 473-479. doi: 10.1094/Phyto-85-473

, , , Population structure of Phytophthora infestans in Turkey reveals expansion and spread of dominant clonal lineages and virulence. Plant Pathol. 70: 898– 911. doi: 10.1111/ppa.13340

Gorzolka K, Perino EHB, Lederer S, et al. (2021) Lysophosphatidylcholine 17:1 from the Leaf Surface of the Wild Potato Species Solanum bulbocastanum Inhibits Phytophthora infestans. J Agric Food Chem. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.0c07199

Goss EM, Tabima JF, Cooke DE, et al. (2014) The Irish potato famine pathogen Phytophthora infestans originated in central Mexico rather than the Andes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 111(24): 8791-6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1401884111

Grandellis C, Fantino E, Muñiz García MN, et al. (2016) StCDPK3 Phosphorylates In Vitro Two Transcription Factors Involved in GA and ABA Signaling in Potato: StRSG1 and StABF1. PLoS ONE11(12): e0167389. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0167389

Grandellis C, Giammaria V, Fantino E, et al. (2016) Transcript profiling reveals that cysteine protease inhibitors are up-regulated in tuber sprouts after extended darkness. Functional & Integrative Genomics 16(4): 399–418. doi: 10.1007/s10142-016-0492-1

Grenville-Briggs LJ, Avrova AO, Bruce CR, et al. (2005) Elevated amino acid biosynthesis in Phytophthora infestans during appressorium formation and potato infection. Fungal Genetics and Biology 42(3): 244-256. doi: 10.1016/j.fgb.2004.11.009

Grenville-Briggs LJ, Anderson VL, Fugelstad J, et al. (2008) Cellulose Synthesis in Phytophthora infestans Is Required for Normal Appressorium Formation and Successful Infection of Potato. The Plant Cell 20(3): 720-738. doi: 10.1105/tpc.107.052043

, , , et al. (2023) A single region of the Phytophthora infestans avirulence effector Avr3b functions in both cell death induction and plant immunity suppression. Molecular Plant Pathology 24: 317– 330. doi: 10.1111/mpp.13298

Guha Roy S, Dey T, Cooke DE, Cooke LR (2021) The dynamics of Phytophthora infestans populations in the major potato‐growing regions of Asia – a review. Plant Pathology Accepted. doi: 10.1111/ppa.13360

Guo D, Li L, Lei Z, et al. (2022) First Report of Late Blight Caused by Phytophthora infestans in Potato in Tibet, China. Plant Dis. 106(3): 1075. doi: 10.1094/PDIS-08-21-1660-PDN

Haas BJ, Kamoun S, Zody MC, et al. (2009) Genome sequence and analysis of the Irish potato famine pathogen Phytophthora infestans. Nature 461: 393–398. doi: 10.1038/nature08358

Hai NTT, Cuong ND, Quyen NT, et al. (2021) Facile Synthesis of Carboxymethyl Cellulose Coated Core/Shell SiO2@Cu Nanoparticles and Their Antifungal Activity against Phytophthora capsici. Polymers (Basel) 13(6): 888. doi: 10.3390/polym13060888

Halterman DA, Kramer LC, Wielgus S, Jiang J (2008) Performance of Transgenic Potato Containing the Late Blight Resistance Gene RB. Plant Disease 92(3): 339-343. doi: 10.1094/PDIS-92-3-0339

. (2017) Integration of pathogen and host resistance information in existing DSSs: Introducing the IPMBlight2. 0 approach. PPO. Spec. Rep. 18: 147-158. Link

Hartill WFT, Young K, Allan DJ, Henshall WR (1990 ) Effects of temperature and leaf wetness on the potato late blight. New Zealand Journal of Crop and Horticultural Science 18: 181-184. doi: 10.1080/01140671.1990.10428093

Haverkort AJ, Boonekamp PM, Hutten R, et al. (2016) Durable Late Blight Resistance in Potato Through Dynamic Varieties Obtained by Cisgenesis: Scientific and Societal Advances in the DuRPh Project. Potato Research 59:35–66. doi: 10.1007/s11540-015-9312-6

He Q, McLellan H, Hughes RK, et al. (2019) Phytophthora infestans effector SFI3 targets potato UBK to suppress early immune transcriptional responses. New Phytologist 222: 438-454. doi: 10.1111/nph.15635

Hernández-Soto I, González-García Y, Juárez-Maldonado A, Hernández-Fuentes AD (2024) Impact of Argemone mexicana L. on tomato plants infected with Phytophthora infestans. PeerJ. 12: e16666. doi: 10.7717/peerj.16666

Hu X, Persson Hodén K, Liao Z, et al. (2021) Phytophthora infestans Ago1-associated miRNA promotes potato late blight disease. New Phytol. doi: 10.1111/nph.17758

Huang Z, Carter N, Lu H, et al. (2018) Translocation of phosphite encourages the protection against Phytophthora infestans in potato: The efficiency and efficacy. Pesticide Biochemistry and Physiology 152: 122-130. doi: 10.1016/j.pestbp.2018.09.007

Huang X, You Z, Luo Y, et al.(2021) Antifungal activity of chitosan against Phytophthora infestans, the pathogen of potato late blight. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 166: 1365-1376. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2020.11.016

, (2024) Modelling the displacement and coexistence of clonal lineages of Phytophthora infestans through revisiting past outbreaks. Plant Pathology 00: 1–13. doi: 10.1111/ppa.13862

Hunter S, Williams N, McDougal R, et al. (2018) Evidence for rapid adaptive evolution of tolerance to chemical treatments in Phytophthora species and its practical implications. PLoS One 13(12): e0208961. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0208961

Huo C, Cao J, Yin R, et al. (2023) First Report of Phytophthora infestans Causing Late Blight on Pepino (Solanum muricatum) in China. Plant Disease. doi: 10.1094/PDIS-04-22-0892-PDN

Hwu F-Y, Lai M-W and Liou R-F (2017) PpMID1 Plays a Role in the Asexual Development and Virulence of Phytophthora parasitica. Frontiers in Microbiology 8: 610. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2017.00610

Iorizzo M, Gao L, Mann H, et al. (2014) A DArT marker-based linkage map for wild potato Solanum bulbocastanum facilitates structural comparisons between SolanumA and B genomes. BMC Genetics 15: 123. doi: 10.1186/s12863-014-0123-6

Islam MH, Shanta SS, Hossain MI, et al. (2023) Phenotypic and Genotypic Analysis of the Population of Phytophthora infestans in Bangladesh Between 2014 and 2019. Potato Res. 66: 255–273. doi: 10.1007/s11540-022-09581-w

Ivanov AA, Ukladov EO, Golubeva TS (2021) Phytophthora infestans: An Overview of Methods and Attempts to Combat Late Blight. Journal of Fungi 7(12): 1071. doi: 10.3390/jof7121071

Ivanov AA, Tyapkin AV, Golubeva TS (2023) How Does the Sample Preparation of Phytophthora infestans Mycelium Affect the Quality of Isolated RNA? Current Issues in Molecular Biology 45(4): 3517-3524. doi: 10.3390/cimb45040230

Ivanov AA, Golubeva TS (2023) Exogenous dsRNA-Induced Silencing of the Phytophthora infestans Elicitin Genes inf1 and inf4 Suppresses Its Pathogenicity on Potato Plants. J Fungi (Basel) 9(11): 1100. doi: 10.3390/jof9111100

Izbiańska K, Floryszak-Wieczorek J, Gajewska J, et al. (2018) RNA and mRNA Nitration as a Novel Metabolic Link in Potato Immune Response to Phytophthora infestans. Frontiers in Plant Science 9:672. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2018.00672

Jacobs MMJ, Vosman B, Vleeshouwers VGAA, et al. (2010) A novel approach to locate Phytophthora infestans resistance genes on the potato genetic map. Theoretical and Applied Genetics 120(4): 785–796. doi: 10.1007/s00122-009-1199-7

Janků M, Jedelská T, Činčalová L, et al. (2022) Structure-activity relationships of oomycete elicitins uncover the role of reactive oxygen and nitrogen species in triggering plant defense responses. Plant Sci. 319: 111239. doi: 10.1016/j.plantsci.2022.111239

Jayawardena RS, Hyde KD, Chen YJ, et al. (2020) One stop shop IV: taxonomic update with molecular phylogeny for important phytopathogenic genera: 76–100 (2020). Fungal Diversity 103: 87–218. doi: 10.1007/s13225-020-00460-8

Jiang R, He Q, Song J, et al. (2023) A Phytophthora infestans RXLR effector AVR8 suppresses plant immunity by targeting a desumoylating isopeptidase DeSI2. Plant J. doi: 10.1111/tpj.16232

Jo K, Kim C, Kim S, et al. (2014) Development of late blight resistant potatoes by cisgene stacking. BMC Biotechnol 14: 50. doi: 10.1186/1472-6750-14-50

Judelson HS, Ah-Fong AMV (2019) Exchanges at the Plant-Oomycete Interface That Influence Disease. Plant Physiology 179(4): 1198–1211. doi: 10.1104/pp.18.00979

Kamoun S, West P, Jong AJ, et al. (1997) A gene encoding a protein elicitor of Phytophthora infestans is down-regulated during infection of potato. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 10: 13–20. doi: 10.1094/MPMI.1997.10.1.13

Kanetis L, Pittas L, Nikoloudakis N, et al. (2021) Characterization of Phytophthora infestans populations in Cyprus, the southernmost potato-producing European country. Plant Disease. doi: 10.1094/PDIS-12-20-2694-RE

Kardile HB, Karkute SG, Challam C, et al. (2023) Hemibiotrophic Phytophthora infestans Modulates the Expression of SWEET Genes in Potato (Solanum tuberosum L.). Plants (Basel) 12(19): 3433. doi: 10.3390/plants12193433

Karki H, Abdullah S, Chen Y, Halterman D (2021) Natural genetic diversity in the potato resistance gene RB confers suppression avoidance from Phytophthora effector IPI-O4. Mol Plant Microbe Interact. doi:10.1094/MPMI-11-20-0313-R

Kasteel M, Ketelaar T, Govers F (2023) Fatal attraction: How Phytophthora zoospores find their host. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 148-149: 13-21. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2023.01.014

Kato H, Nemoto K, Shimizu M, et al. (2021) Pathogen-derived 9-methyl sphingoid base is perceived by a lectin receptor kinase in Arabidopsis. bioRxiv 2021.10.18.464766; doi: 10.1101/2021.10.18.464766

Kato F, Ando Y, Tanaka A, et al. (2022) Synthesis of aglycones, structure-activity relationships, and mode of action of lycosides as inhibitors of the asexual reproduction of Phytophthora. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. : zbac179. doi: 10.1093/bbb/zbac179

King F, Yuen ELH, Bozkurt TO (2023) Border Control: Manipulation of the Host-Pathogen Interface by Perihaustorial Oomycete Effectors. Mol Plant Microbe Interact. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-09-23-0122-FI

Krämer R, Freytag S, Schmelzer E (1997) In vitro formation of infection structures of Phytophthora infestans is associated with synthesis of stage specific polypeptides. European Journal of Plant Pathology 103: 43–53 doi: 10.1023/A:1008688919285

Kronmiller BA, Feau N, Shen D, et al. (2023) Comparative Genomic Analysis of 31 Phytophthora Genomes Reveals Genome Plasticity and Horizontal Gene Transfer. Mol Plant Microbe Interact. 36(1): 26-46. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-06-22-0133-R

Larson ER, Migliano LE, Chen Y, Gevens AJ (2021) Mefenoxam Sensitivity in US-8 and US-23 Phytophthora infestans from Wisconsin. Plant Health Progress. doi: 10.1094/PHP-02-21-0044-FI

Latijnhouwers M, Ligterink W, Vleeshouwers VG, et al. (2004) A Gα subunit controls zoospore motility and virulence in the potato late blight pathogen Phytophthora infestans. Molecular Microbiology 51: 925-936. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03893.x

Lawrence SA, Robinson HF, Furkert DP, et al. (2021) Screening a Natural Product-Inspired Library for Anti-Phytophthora Activities. Molecules 26(7): 1819. doi: 10.3390/molecules26071819

Lee H, Kim S, Oh S, et al. (2014) Multiple recognition of RXLR effectors is associated with nonhost resistance of pepper against Phytophthora infestans. New Phytol. 203, 926–938. doi: 10.1111/nph.12861

Lee JH, Lee SE, OhS, Seo E, Choi D (2018) HSP70s Enhance a Phytophthora infestans Effector-Induced Cell Death via an MAPK Cascade in Nicotiana benthamiana. Molecular Plant-Microbe Interactions 31(3): 356-362. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-07-17-0156-R

Lee S, Lee HY, Kang HJ, et al. (2023) Oomycete effector AVRblb2 targets cyclic nucleotide-gated channels through calcium sensors to suppress pattern-triggered immunity. New Phytol. doi: 10.1111/nph.19430

Leesutthiphonchai W, Vu AL, Ah-Fong AMV, Judelson HS (2018) How Does Phytophthora infestans Evade Control Efforts? Modern Insight Into the Late Blight Disease. Phytopathology 108(8): 916-924. doi: 10.1094/PHYTO-04-18-0130-IA

Lebecka R, Sobkowiak S (2013) Host–pathogen interaction between Phytophthora infestans and Solanum tuberosum following exposure to short and long daylight hours. Acta Physiol Plant 35: 1131–1139. doi: 10.1007/s11738-012-1150-4

Li Y, Cooke DE, Jacobsen E, van der Lee T (2013) Efficient multiplex simple sequence repeat genotyping of the oomycete plant pathogen Phytophthora infestans. J Microbiol Methods. 92(3): 316-22. doi: 10.1016/j.mimet.2012.11.021

Li H, Hu R, Fan Z, et al. (2022) Dual RNA Sequencing Reveals the Genome-Wide Expression Profiles During the Compatible and Incompatible Interactions Between Solanum tuberosum and Phytophthora infestans. Front Plant Sci. 13: 817199. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2022.817199

Lin X, Witek K, Witek A, et al. (2019) The recognition of conserved RxLR effectors of Phytophthora species might help to defeat multiple oomycete diseases. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 32: S11–S1212. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-32-10-S1.1

Lin et al. (2021) Rpi-amr3 confers resistance to multiple Phytophthora species by recognizing a conserved RXLR effector.

Lin X, Olave-Achury A, Heal R, et al. (2022) A potato late blight resistance gene protects against multiple Phytophthora species by recognizing a broadly conserved RXLR-WY effector. Molecular Plant. doi: 10.1016/j.molp.2022.07.012

Lin X, Torres Ascurra YC, Fillianti H, et al. (2023) Recognition of Pep-13/25 MAMPs of Phytophthora localizes to an RLK locus in Solanum microdontum. Front Plant Sci. 13: 1037030. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2022.1037030

Lin X, Jia Y, Heal R, et al. (2023) Solanum americanum genome-assisted discovery of immune receptors that detect potato late blight pathogen effectors. Nat Genet. doi: 10.1038/s41588-023-01486-9

Lindqvist‐Kreuze H, Gamboa S, Izarra M, et al. (2019) Population structure and host range of the potato late blight pathogen Phytophthora infestans in Peru spanning two decades. Plant Pathol. doi:10.1111/ppa.13125

Lobato MC, Daleo GR, Andreu AB, et al. (2017) Cell Wall Reinforcement in the Potato Tuber Periderm After Crop Treatment with Potassium Phosphite. Potato Research: 1–11. doi: 10.1007/s11540-017-9349-9

Lucca AMF, Puebla AF, Cabarrou G, et al. (2020) MIP 2.0 para el control sostenible del tizón tardío de la papa en Argentina. Visión Rural 27 (135): 37-42. Link

Luo X, Tian T, Bonnave M, et al. (2021) The molecular mechanisms of Phytophthora infestans in response to reactive oxygen species (ROS) stress. Phytopathology. doi: 10.1094/PHYTO-08-20-0321-R

, , (2023) Sensitivity of dominant UK Phytophthora infestans genotypes to a range of fungicide active ingredients. Plant Pathology 00: 1–12. doi: 10.1111/ppa.13832

Mabon R, Guibert M, Corbière R, Andrivon D (2021) An Improved PCR Method for Rapid and Accurate Identification of Mating Types in the Late Blight Pathogen Phytophthora infestans. Plant Health Progress. doi: 10.1094/PHP-02-21-0026-FI

Mach J (2008) Cellulose Synthesis in Phytophthora infestans Pathogenesis. The Plant Cell 20 (3) 500; doi: 10.1105/tpc.108.200312

Mach J (2021) Phytophthora infestans RXLR effectors target vesicle trafficking. Plant Cell. 33(5): 1401-1402. doi: 10.1093/plcell/koab072

Mandal K, Dutta S, Upadhyay A, et al. (2022) Comparative Genome Analysis Across 128 Phytophthora Isolates Reveal Species-Specific Microsatellite Distribution and Localized Evolution of Compartmentalized Genomes. Front Microbiol. 13: 806398. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2022.806398

Mao S, Zhao J, Ding X, et al. (2023) Integrated Sensing Chip for Ultrasensitive Label-Free Detection of the Products of Loop-Mediated Isothermal Amplification. ACS Sens. 8(6): 2255-2262. doi: 10.1021/acssensors.3c00227

Maridueña-Zavala MG, Freire-Peñaherrera A, Cevallos-Cevallos JM, et al. (2017) GC-MS metabolite profiling of Phytophthora infestans resistant to metalaxyl. European Journal of Plant Pathology 149(3): 563-574. doi: 10.1007/s10658-017-1204-y

Martin M, Cappellini E, Samaniego J, et al. (2013) Reconstructing genome evolution in historic samples of the Irish potato famine pathogen. Nat Commun 4: 2172. doi: 10.1038/ncomms3172

Martin MD, Vieira FG, Ho SY, et al. (2016) Genomic Characterization of a South American Phytophthora Hybrid Mandates Reassessment of the Geographic Origins of Phytophthora infestans. Mol Biol Evol. 33(2): 478-91. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msv241

Martini F, Jijakli MH, Gontier E, et al. (2023) Harnessing Plant’s Arsenal: Essential Oils as Promising Tools for Sustainable Management of Potato Late Blight Disease Caused by Phytophthora infestans-A Comprehensive Review. Molecules 28(21): 7302. doi: 10.3390/molecules28217302

Matson MEH, Liang Q, Lonardi S, Judelson HS (2022) Karyotype variation, spontaneous genome rearrangements affecting chemical insensitivity, and expression level polymorphisms in the plant pathogen Phytophthora infestans revealed using its first chromosome-scale assembly. PLoS Pathog 18(10): e1010869. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1010869

Mazumdar P, Singh P, Kethiravan D, et al. (2021) Late blight in tomato: insights into the pathogenesis of the aggressive pathogen Phytophthora infestans and future research priorities. Planta 253(6): 119. doi: 10.1007/s00425-021-03636-x

McLeod A, De Villiers D, Sullivan L, et al. (2023) First report of Phytophthora infestans lineage EU23 causing potato and tomato late blight in South Africa. Plant Dis. doi: 10.1094/PDIS-08-23-1511-PDN

Meijer HJ, Schoina C, Wang S, et al. (2018) Phytophthora infestanssmall phospholipase D‐like proteins elicit plant cell death and promote virulence. Molecular Plant Pathology. Accepted Author Manuscript. doi:10.1111/mpp.12746

Monjil MS, Kato H, Matsuda K, et al. (2021) Two structurally different oomycete MAMPs induce distinctive plant immune responses. bioRxiv 2021.10.22.465218. doi: 10.1101/2021.10.22.465218

Moon KB, Park SJ, Park JS, et al. (2022) Editing of StSR4 by Cas9-RNPs confers resistance to Phytophthora infestans in potato. Front Plant Sci. 13: 997888. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2022.997888

Mu Y, Guo X, Yu J, et al. (2022) SWATH-MS based quantitative proteomics analysis reveals novel proteins involved in PAMP triggered immunity against potato late blight pathogen Phytophthora infestans. Front Plant Sci. 13: 1036637. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2022.1036637

Naveed ZA, Bibi S, Ali GS (2019) The Phytophthora RXLR effector Avrblb2 modulates plant immunity by interfering with Ca2+ signaling pathway. Front. Plant Sci. 10: 374. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2019.00374

Neupane K, Ghimire B, Baysal-Gurel F (2022) Efficacy and Timing of Application of Fungicides, Biofungicides, Host-Plant Defense Inducers, and Fertilizer to Control Phytophthora Root Rot of Flowering Dogwoods in Simulated Flooding Conditions in Container Production. Plant Disease. doi: 10.1094/PDIS-02-22-0437-RE

Nyankanga F, Njogu M, Muthomi J, Olanya M (2012) Efficacy of fungicide combinations, phosphoric acid and plant extract from stinging nettle on potato late blight management and tuber yield. Archives of Phytopathology and Plant Protection 45(12): 1449-1463. doi: 10.1080/03235408.2012.676818

Oh SK, Young C, Lee M, et al. (2009) In planta expression screens of Phytophthora infestans RXLR effectors reveal diverse phenotypes, including activation of the Solanum bulbocastanum disease resistance protein Rpi-blb2. Plant Cell 21: 2928–2947. doi: 10.1105/tpc.109.068247

Oh S, Kim S, oPark HJ, et al. (2023) Nucleotide-binding leucine-rich repeat network underlies nonhost resistance of pepper against the Irish potato famine pathogen Phytophthora infestans. Plant Biotechnol J. doi: 10.1111/pbi.14039

Olivieri FP, Lobato MC, Machinandiarena MF, et al. (2023) Undaria pinnatifida Aqueous Extract Activates Potato Defense Responses Against P. Infestans. SSRN. doi: 10.2139/ssrn.4418779

Osawa H, Suzuki N, Akino S, et al. (2021) Quantification of Phytophthora infestans population densities and their changes in potato field soil using real-time PCR. Sci Rep 11: 6266. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-85492-z

Oyarzun PJ, Pozo A, Ordoñez ME, et al. (1998) Host Specificity of Phytophthora infestans on Tomato and Potato in Ecuador. Phytopathology 88(3): 265-71. doi: 10.1094/PHYTO.1998.88.3.265

Pais M, Yoshida K, Giannakopoulou A, et al. (2018) Gene expression polymorphism underpins evasion of host immunity in an asexual lineage of the Irish potato famine pathogen. BMC Evolutionary Biology 18:93. doi: 10.1186/s12862-018-1201-6

Panda A, Sen D, Ghosh A, et al. (2018) EumicrobeDBLite: a lightweight genomic resource and analytic platform for draft oomycete genomes. Molecular Plant Pathology 19: 227–237. doi: 10.1111/mpp.12505

Pandey P, Leary AY, Tümtas Y, Savage Z, et al. (2020) The Irish potato famine pathogen subverts host vesicle trafficking to channel starvation-induced autophagy to the pathogen interface. bioRxiv 2020.03.20.000117; doi: 10.1101/2020.03.20.000117

Pandey P, Leary AY, Tumtas Y, et al. (2021) An oomycete effector subverts host vesicle trafficking to channel starvation-induced autophagy to the pathogen interface. Elife. 10: e65285. doi: 10.7554/eLife.65285.

Panstruga R, Dodds PN (2009) Terrific protein traffic: the mystery of effector protein delivery by filamentous plant pathogens. Science 324(5928): 748–750. doi: 10.1126/science.1171652

Patil VU, Vanishree G, Pattanayak D, et al. (2017) Complete mitogenome mapping of potato late blight pathogen, Phytophthora infestans A2 mating type. Mitochondrial DNA B Resour 2(1): 90-91. doi: 10.1080/23802359.2017.1280699

Perez W, Alarcon L, Rojas T, et al. (2022) Screening South American Potato Landraces and Potato Wild Relatives for Novel Sources of Late Blight Resistance. Plant Disease 106(7): 1845-1856. doi: 10.1094/PDIS-07-21-1582-RE

Patarroyo C, Lucca F, Dupas S, Restrepo S (2024) Reconstructing the global migration history of Phytophthora infestans towards Colombia. Phytopathology. doi: 10.1094/PHYTO-05-24-0163-R

Peters RD, Al-Mughrabi KI, Kalischuk ML, et al. (2014) Characterization of Phytophthora infestans population diversity in Canada reveals increased migration and genotype recombination. Canadian Journal of Plant Pathology 36(1): 73-82. doi: 10.1080/07060661.2014.892900

Petre B, Contreras MP, Bozkurt TO, et al. (2021) Host-interactor screens of Phytophthora infestans RXLR proteins reveal vesicle trafficking as a major effector-targeted process. The Plant Cell koab069. doi: 10.1093/plcell/koab069

Pirc K, Clifton LA, Yilmaz N, et al. (2022) An oomycete NLP cytolysin forms transient small pores in lipid membranes. Sci Adv. 8(10): eabj9406. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.abj9406

Pomerantz A, Cohen Y, Shufan E, et al. (2014) Characterization of Phytophthora infestans resistance to mefenoxam using FTIR spectroscopy. Journal of Photochemistry and Photobiology B: Biology

141: 308-314. doi: 10.1016/j.jphotobiol.2014.10.005

Poppel PMJA, Guo J, Vondervoort PJI, et al. (2008) The Phytophthora infestans avirulence gene Avr4 encodes an RXLR-dEER effector. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 21: 1460–1470. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-21-11-1460

Qin CF, He MH, Chen FP, et al. (2016) Comparative analyses of fungicide sensitivity and SSR marker variations indicate a low risk of developing azoxystrobin resistance in Phytophthora infestans. Nature Scientific Reports 6: 20483. doi: 10.1038/srep20483

Raza W, Ghazanfar MU, Sullivan L, et al. (2021) Mating Type and Aggressiveness of Phytophthora infestans (Mont.) de Bary in Potato-Growing Areas of Punjab, Pakistan, 2017–2018 and Identification of Genotype 13_A2 in 2019–2020. Potato Res. 64: 115–129. doi: 10.1007/s11540-020-09467-9

Resjö S, Brus M, Ali A, et al. (2017) Proteomic Analysis of Phytophthora infestans Reveals the Importance of Cell Wall Proteins in Pathogenicity. Molecular & Cellular Proteomics 16: 1958-1971. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M116.065656

Ristaino J, Cooke DE, Acuña I, Muñoz M (2020) The threat of late blight to global food security. En: Emerging Plant Diseases and Global Food Security (eds J. Ristaino & A. Records) 101–133 (American Phytopathological Society Press). doi: 10.1094/9780890546383.006

Ritchie F, Bain RA, Lees AK, Boor TR, Paveley ND (2018) Integrated control of potato late blight: predicting the combined efficacy of host resistance and fungicides. Plant Pathology 67: 1784-1791. doi: 10.1111/ppa.12887

Rodenburg SYA, Seidl MF, de Ridder D, Govers F (2021) Uncovering the Role of Metabolism in Oomycete–Host Interactions Using Genome-Scale Metabolic Models. Front. Microbiol. 12: 748178. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2021.748178

Rogozhin EA, Vasilchenko AS, Barashkova AS, et al. (2020) Peptide Extracts from Seven Medicinal Plants Discovered to Inhibit Oomycete Phytophthora infestans, a Causative Agent of Potato Late Blight Disease. Plants 9(10): 1294. doi: 10.3390/plants9101294

Runno-Paurson E, Agho CA, Nassar H, et al. (2023) The variability of Phytophthora infestans isolates collected from Estonian islands in the Baltic Sea. Plant Dis. doi: 10.1094/PDIS-07-23-1399-RE

Santin F, Bhogale S, Fantino E, et al. (2016) Solanum tuberosum StCDPK1 is regulated by miR390 at the posttranscriptional level and phosphorylates the auxin efflux carrier StPIN4 in vitro, a potential downstream target in potato development. Physiologia plantarum 159(2): 244–261. doi: 10.1111/ppl.12517

Savage Z, Duggan C, Toufexi A (2021) Chloroplasts alter their morphology and accumulate at the pathogen interface during infection by Phytophthora infestans. Plant J, 107: 1771-1787. doi: 10.1111/tpj.15416

Savage Z, Erickson JL, Prautsch J, et al. (2021) Chloroplast movement and positioning protein CHUP1 is required for focal immunity against Phytophthora infestans. bioRxiv 2021.10.08.463641. doi: 10.1101/2021.10.08.463641

Saville A, Graham K, Grünwald NJ, et al. (2015) Fungicide Sensitivity of U.S. Genotypes of Phytophthora infestans to Six Oomycete-Targeted Compounds. Plant Disease 99(5): 659-666. doi: 10.1094/PDIS-05-14-0452-RE

Saville AC, Ristaino JB (2021) Global historic pandemics caused by the FAM-1 genotype of Phytophthora infestans on six continents. Scientific Reports 11(1): 12335. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-90937-6

, , , et al (2021) Population structure of Phytophthora infestans collected on potato and tomato in Italy. Plant Pathology 00: 1– 14. doi: 10.1111/ppa.13444

Schepers HTAM, Kessel GJT, Lucca F, et al. (2018) Reduced efficacy of fluazinam against Phytophthora infestans in the Netherlands. Eur J Plant Pathol 151: 947. doi: 10.1007/s10658-018-1430-y

Schoina C, Govers F (2015) The Oomycete Phytophthora infestans, the Irish Potato Famine Pathogen. In: Lugtenberg B. (eds) Principles of Plant-Microbe Interactions. Springer, Cham. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-08575-3_39

, , , et al. (2021) Mining oomycete proteomes for metalloproteases leads to identification of candidate virulence factors in Phytophthora infestans. Molecular Plant Pathology 00: 1– 13. doi: 10.1111/mpp.13043

Seo JH, Choi JG, Park HJ, et al. (2022) Complete Mitochondrial Genome Sequences of Korean Phytophthora infestans Isolates and Comparative Analysis of Mitochondrial Haplotypes. Plant Pathol J. 38(5): 541-549. doi: 10.5423/PPJ.OA.07.2022.0093

Shandil RK, Chakrabarti SK, Singh BP, et al. Genotypic background of the recipient plant is crucial for conferring RB gene mediated late blight resistance in potato. BMC Genetics 18: 22. doi: 10.1186/s12863-017-0490-x

Shen LL, Waheed A, Wang YP, et al. (2022) Mitochondrial Genome Contributes to the Thermal Adaptation of the Oomycete Phytophthora infestans. Front Microbiol. 13: 928464. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2022.928464

Shimelash D, Dessie B (2020) Novel characteristics of Phytophthora infestans causing late blight on potato in Ethiopia. Current Plant Biology 24: 100172. doi: 10.1016/j.cpb.2020.100172

Situ J, Xi P, Lin L, et al. (2022) Signal and regulatory mechanisms involved in spore development of Phytophthora and Peronophythora. Front Microbiol. 13: 984672. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2022.984672

Soliman A, Adam LR, Rehal PK, Daayf F (2021) Overexpression of Solanum tuberosum respiratory burst oxidase homolog A (StRbohA) promotes potato tolerance to Phytophthora infestans. Phytopathology. doi: 10.1094/PHYTO-10-20-0482-R

Stefańczyk E, Brylińska M, Brurberg MB, et al. (2018) Diversity of Avr‐vnt1 and AvrSmira1 effector genes in Polish and Norwegian populations of Phytophthora infestans. Plant Pathology 67: 1792-1802. doi: 10.1111/ppa.12875

Stellingwerf JS, Phelan S, Doohan FM, et al. (2018) Evidence for selection pressure from resistant potato genotypes but not from fungicide application within a clonal Phytophthora infestans population. Plant Pathol 67: 1528-1538. doi: 10.1111/ppa.12852

Sun K, Wolters AMA, Vossen JH, et al. (2016) Silencing of six susceptibility genes results in potato late blight resistance. Transgenic Research (online). doi: 10.1007/s11248-016-9964-2

Sun H, Jiao WB, Krause K, et al. (2022) Chromosome-scale and haplotype-resolved genome assembly of a tetraploid potato cultivar. Nat Genet. doi: 10.1038/s41588-022-01015-0

Sundaresha S, Sharma S, Bairwa A, et al. (2022), Spraying of dsRNA molecules derived from Phytophthora infestans, along with nano clay carriers as a proof of concept for developing novel protection strategy for Potato late blight. Pest Manag Sci. doi: 10.1002/ps.6949

Thilliez GJ, Armstrong MR, Lim T, et al. (2018) Pathogen enrichment sequencing (PenSeq) enables population genomic studies in oomycetes. New Phytologist. doi: 10.1111/nph.15441

van West P, Shepherd SJ, Walker CA, et al. (2008) Internuclear gene silencing in Phytophthora infestans is established through chromatin remodelling. Microbiology 154: 1482–1490. doi:

Van Weymers PSM, Baker K, Chen X, et al. (2016) Utilizing “Omic” Technologies to Identify and Prioritize Novel Sources of Resistance to the Oomycete Pathogen Phytophthora infestans in Potato Germplasm Collections. Frontiers in plant science 7: 672. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2016.00672

Vleeshouwers VGAA, Raffaele S, Vossen JH, et al. (2011) Understanding and Exploiting Late Blight Resistance in the Age of Effectors. Annual Review of Phytopathology 49: 507-531. doi: 10.1146/annurev-phyto-072910-095326

Tani S, Nishio N, Kai K, et al. (2020) Chemical genetic approach using β-rubromycin reveals that a RIO kinase-like protein is involved in morphological development in Phytophthora infestans. Scientific Reports 10(1): 22326. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-79326-7

Tomczynska I, Stumpe M, Mauch F (2018) A conserved RxLR effector interacts with host RABA‐type GTPases to inhibit vesicle‐mediated secretion of antimicrobial proteins. The Plant Journal 95: 187-203. doi: 10.1111/tpj.13928

, (2023) Spatiotemporal analysis of Phytophthora infestans population diversity and disease risk in Great Britain. Plant Pathology 00, 1– 11. doi: 10.1111/ppa.13697

Torto TA, Li S, Styer A, et al. (2003) EST mining and functional expression assays identify extracellular effector proteins from the plant pathogen Phytophthora. Genome Res. 13: 1675–1685. doi: 10.1101/gr.910003

Tyler BM, Tripathy S, Zhang X, et al. (2006) Phytophthora genome sequences uncover evolutionary origins and mechanisms of pathogenesis. Science 313: 1261–1266. doi: 10.1126/science.1128796

van Damme M, Cano LM, Oliva R, et al. (2011) Evolutionary and Functional Dynamics of Oomycete Effector Genes. In Effectors in Plant–Microbe Interactions (eds Martin F, Kamoun S). doi: 10.1002/9781119949138.ch5

van Damme M, Bozkurt TO, Cakir C, et al. (2015 ) The Irish potato famine pathogen Phytophthora infestans translocates the CRN8 kinase into host plant cells. PLoS Pathog. 2012;8(8):e1002875. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002875. Epub 2012 Aug 23. Erratum in: PLoS Pathog. 11(3): e1004753. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002875

van Poppel PM, Guo J, van de Vondervoort PJ, et al. (2008) The Phytophthora infestans avirulence gene Avr4 encodes an RXLR-dEER effector. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 21> 1460–1470. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-21-11-1460

Varghese B, Valsalan R, Mathew D (2022) Novel MicroRNAs and their Functional Targets from Phytophthora infestans and Phytophthora cinnamomi. Curr Genomics. 23(1): 41-49. doi: 10.2174/1389202923666211223122305

Waheed A, Wang YP, Nkurikiyimfura O, et al. (2021) Effector Avr4 in Phytophthora infestans Escapes Host Immunity Mainly Through Early Termination. Front Microbiol. 12: 646062. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2021.646062

Wang S, Boevink PC, Welsh L, et al. (2017) Delivery of cytoplasmic and apoplastic effectors from Phytophthora infestans haustoria by distinct secretion pathways. New Phytologist 216(1): 205–215. doi: 10.1111/nph.14696

Wang W, Jiao F (2019) Effectors of Phytophthora pathogens are powerful weapons for manipulating host immunity. Planta 250: 413–425. doi: 10.1007/s00425-019-03219-x

, , , et al. (2021) A nonspecific lipid transfer protein, StLTP10, mediates resistance to Phytophthora infestans in potato. Molecular Plant Pathology 22: 48– 63. doi: 10.1111/mpp.13007

Wang M, Du Y, Ling C, et al. (2021) Design, Synthesis and Antifungal/Anti‐Oomycete Activity of Pyrazolyl Oxime Ethers as Novel Potential Succinate Dehydrogenase Inhibitors. Pest Manag Sci. Accepted Author Manuscript. doi: 10.1002/ps.6418

Wang W, Liu Y, Xue Z, Li J, et al., (2021) Activity of the Novel Fungicide SYP-34773 against Plant Pathogens and Its Mode of Action on Phytophthora infestans. J Agric Food Chem. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.1c02679

Wang H, Trusch F, Turnbull D, et al. (2021) Evolutionarily distinct resistance proteins detect a pathogen effector through its association with different host targets. New Phytol. 232: 1368-1381. doi: 10.1111/nph.17660

Wang H, Xiang Y, Wang D, Fu ZQ (2022) An epic war between an oomycete pathogen and plants. Mol Plant. S1674-2052(22)00360-4. doi: 10.1016/j.molp.2022.10.008

Wang Z, Ke Q, Tao K, et al. (2022) Activity and Point Mutation G699V in PcoORP1 Confer Resistance to Oxathiapiprolin in Phytophthora colocasiae Field Isolates. J Agric Food Chem. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.2c06707

Wang T, Lv JL, Xu J, et al. (2022) The catalase-peroxidase PiCP1 plays a critical role in abiotic stress resistance, pathogenicity, and asexual structure development in Phytophthora infestans. Environ Microbiol. doi: 10.1111/1462-2920.16305

Wang Z, Li T, Zhang X, et al. (2023) A Phytophthora infestans RXLR effector targets a potato ubiquitin-like domain-containing protein to inhibit the proteasome activity and hamper plant immunity. New Phytol. doi: 10.1111/nph.18749

Wang Z, Su C, Hu W, et al. (2023) The effectors of Phytophthora infestans impact host immunity upon regulation of antagonistic hormonal activities. Planta 258(3): 59. doi: 10.1007/s00425-023-04215-y

Wang B, Yang J, Zhao X, et al. (2023) Antifungal activity of the botanical compound rhein against Phytophthora capsici and the underlying mechanisms. Pest Manag Sci. doi: 10.1002/ps.7852

Wang Y, Sun Y, Li Y, et al. (2023) Genome-wide identification and expression profiles of the Phytophthora infestans responsive CYPome (Cytochrome P450 complement) in Solanum tuberosum. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem.: zbad180. doi: 10.1093/bbb/zbad180

Welsh L, Thorpe P, Whisson SC, et al. (2018) The Phytophthora infestans Haustorium Is a Site for Secretion of Diverse Classes of Infection-Associated Proteins. mBio Aug 9 (4) e01216-18. doi: 10.1128/mBio.01216-18

, , , (2023) Genotypic characterization of Phytophthora infestans populations in Bangladesh. Plant Pathology 00: 1– 13. doi: 10.1111/ppa.13725

Whisson SC, Boevink PC, Wang S, Birch PRJ (2016) The cell biology of late blight disease. Current Opinion in Microbiology 34: 127–135. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2016.09.002

Winkworth RC, Neal G, Ogas RA, et al. (2022) Comparative analyses of complete Peronosporaceae (Oomycota) mitogenome sequences – insights into structural evolution and phylogeny. Genome Biol Evol. evac049. doi: 10.1093/gbe/evac049

Witek K, Lin X, Karki HS, et al. (2021) A complex resistance locus in Solanum americanum recognizes a conserved Phytophthora effector. Nat. Plants 7: 198–208. doi: 10.1038/s41477-021-00854-9

Wu EJ, Wang YP, Yang LN, et al. (2022) Elevating Air Temperature May Enhance Future Epidemic Risk of the Plant Pathogen Phytophthora infestans. J Fungi (Basel) 8(8):808. doi: 10.3390/jof8080808

Xiong Y, Zhao D, Chen S, et al. (2023) Deciphering the underlying immune network of the potato defense response inhibition by Phytophthora infestans nuclear effector Pi07586 through transcriptome analysis. Front Plant Sci. 14: 1269959. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2023.1269959

Yan J, Li Q, Geng D, et al. (2025) The Potato StNAC2-StSABP2 Module Enhanced Resistance to Phytophthora infestans Through Activating the Salicylic Acid Pathway. Mol Plant Pathol, 26: e70081. doi: 10.1111/mpp.70081

Yang L, Wang D, Xu Y, et al. (2017) A New Resistance Gene against Potato Late Blight Originating from Solanum pinnatisectum Located on Potato Chromosome 7. Frontiers in Plant Science 8: 1729. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2017.01729

Yang X, Guo X, Yang Y, et al. (2018) Gene Profiling in Late Blight Resistance in Potato Genotype SD20. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 19(6): 1728. doi: 10.3390/ijms19061728

Yang LN, Liu H, Duan GH, et al. (2020) The Phytophthora infestans AVR2 Effector Escapes R2 Recognition Through Effector Disordering. Mol Plant Microbe Interact. 33(7):921-931. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-07-19-0179-R

Yang LN, Ouyang H, Nkurikiyimfura O, et al. (2022) Genetic variation along an altitudinal gradient in the Phytophthora infestans effector gene Pi02860. Front Microbiol. 13: 972928. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2022.972928

Yin J, Gu B, Huang G, et al. (2017) Conserved RXLR Effector Genes of Phytophthora infestans Expressed at the Early Stage of Potato Infection Are Suppressive to Host Defense. Frontiers in Plant Science 8: 2155. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2017.02155

Yoshida K, Schuenemann VJ, Cano LM, et al. (2013) The rise and fall of the Phytophthora infestans lineage that triggered the Irish potato famine. Baulcombe D, ed. eLife. 2013;2:e00731. doi: 10.7554/eLife.00731

Yuen JE, Forbes GA (2009) Estimating the level of susceptibility to Phytophthora infestans in potato genotypes. Phytopathology 99(6): 782-786. doi: 10.1094/PHYTO-99-6-0782

Yuen J (2021) Pathogens which threaten food security: Phytophthora infestans, the potato late blight pathogen. Food Sec. 13: 247–253. doi: 10.1007/s12571-021-01141-3

Zadoks JC (2008) The Potato Murrain on the European Continent and the Revolutions of 1848. Potato Res. 51: 5–45. doi: 10.1007/s11540-008-9091-4

Zaynab M, Peng J, Sharif Y, et al. (2021) Expression profiling of pathogenesis-related Protein-1 (PR-1) genes from Solanum tuberosum reveals its critical role in phytophthora infestans infection. Microb Pathog. 161(Pt B): 105290. doi: 10.1016/j.micpath.2021.105290

, , Regressive evolution of an effector following a host jump in the Irish Potato Famine Pathogen Lineage.

Zhang S, Zheng X, Reiter RJ, et al. (2017) Melatonin Attenuates Potato Late Blight by Disrupting Cell Growth, Stress Tolerance, Fungicide Susceptibility and Homeostasis of Gene Expression in Phytophthora infestans. Frontiers in Plant Science 8: 1993. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2017.01993

Zhang F, Chen H, Zhang X, et al. (2020) Genome analysis of two newly emerged potato late blight isolates shed lights on pathogen adaptation and provides tools for disease management. Phytopathology. doi: 10.1094/PHYTO-05-20-0208-FI

, , , et al. (2021) Potato StMPK7 is a downstream component of StMKK1 and promotes resistance to the oomycete pathogen Phytophthora infestans. Molecular Plant Pathology 00: 1– 14. doi: 10.1111/mpp.13050

Zheng X, Wagener N, McLellan H, et al. (2018) Phytophthora infestans RXLR effector SFI5 requires association with calmodulin for PTI/MTI suppressing activity. New Phytologist 219: 1433-1446. doi: 10.1111/nph.15250

Zheng J, Duan S, Armstrong MR, et al. (2020) New Findings on the Resistance Mechanism of an Elite Diploid Wild Potato Species JAM1-4 in Response to a Super Race Strain of Phytophthora infestans. Phytopathology 110(8): 1375-1387. doi: 10.1094/PHYTO-09-19-0331-R

Zheng K, Lu J, Li J, et al. (2021) Efficiency of chitosan application against Phytophthora infestans and the activation of defence mechanisms in potato. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2021.05.097

Zheng H, You L, Meng S, et al. (2023) Unraveling the mysteries of (L)WY-domain oomycete effectors. Sci Bull (Beijing): S2095-9273(23)00730-2. doi: 10.1016/j.scib.2023.10.030

Zhou J, Qi Y, Nie J, et al. (2022) A Phytophthora effector promotes homodimerization of host transcription factor StKNOX3 to enhance susceptibility. J Exp Bot.: erac308. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erac308

Zhu J, Tang X, Sun Y, et al. (2022) Comparative Metabolomic Profiling of Compatible and Incompatible Interactions Between Potato and Phytophthora infestans. Front Microbiol. 13: 857160. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2022.857160