.

Condición fitosanitaria: Presente

Grupo de cultivos: Cereales

Especie hospedante: Cebada (Hordeum vulgare; Hordeum vulgare var. distichon (L.) Hook.f., 1896)

Rango de hospedantes: medianamente específico / estrecho. Se considera que Hordeum vulgare y H. vulgare ssp. spontaneum son los hospedantes principales de P. teres. Sin embargo, se ha observado la infección natural por P. teres en otras especies silvestres de Hordeum y especies relacionadas de los géneros Bromus, Avena y Triticum, incluidos H. marinum, H. murinum, H. brachyantherum, H. distichon, H. hystrix, B . diandrus, A. fatua, A. sativa y T. aestivum (Shipton et al., 1973). En experimentos de inoculación artificial en condiciones de campo, P. teres f. teres ha demostrado infectar un amplio rango de especies gramíneas de los géneros Agropyron, Brachypodium, Elymus, Cynodon, Deschampsia, Hordelymus y Stipa (Brown et al., 1993). Además, en un estudio en cámara de crecimiento se utilizaron 43 especies de gramíneas y al menos un aislado de P. teres f. teres fue capaz de infectar 28 de las 43 especies analizadas. Sin embargo, de estas 28 especies, 14 exhibieron reacciones débiles de tipo 1 o 2 en la escala NFNB 1-10 (Tekauz, 1985). Estos tipos de reacciones son pequeñas lesiones puntiformes y posiblemente podrían interpretarse como reacciones que no son del hospedante. Además, P. teres f. teres se investigó en condiciones de campo mediante la inoculación artificial de 95 especies de gramíneas con rastrojo de cebada infectado naturalmente. Pyrenophora teres f. teres se volvió a aislar de 65 de las especies cuando se incubaron hojas infectadas de plantas adultas en placas de agar nutritivo; sin embargo, aparte de las especies de Hordeum, solo dos de las 65 especies hospedantes exhibieron tipos de reacción de campo moderadamente susceptibles o susceptibles, y la mayoría de las especies mostraron pequeñas lesiones necróticas oscuras indicativas de una respuesta altamente resistente a P. teres f. teres (resistencia no-hospedante). Aunque estas especies silvestres tienen el potencial de ser hospedantes alternativos, el alto nivel de resistencia identificado para la mayoría de las especies hace que su función como fuente de inóculo primario sea cuestionable.

Otros estudios más recientes han demostrado, mediante experimentos de patogenicidad y estudios moleculares, la especificidad de P. teres f. teres por el hospedante; ya que aislados de Ptt de cebada y la especie Hordeum murinum (cola de zorro) no pudieron infectar de manera cruzada a los respectivamente hospedantes (Linde y Smith, 2019).

Etiología: Hongo. Necrotrófico

Agente causal: Drechslera teres (Sacc.) Shoemaker, 1959 (anamorfo), Pyrenophora teres Drechsler, 1923 (teleomorfo)

Taxonomía: Eukaryota > Fungi > Dikarya > Ascomycota > Pezizomycotina > Dothideomycetes > Pleosporomycetidae > Pleosporales > Pleosporaceae > Pyrenophora

Formas: la mancha en red existe en dos formas fenotípicas (síntomas) diferentes: la típica mancha reticular (tipo en red) causada por P. teres f. teres Smedeg. (Ptt) y lesiones circulares o elípticas marrón oscuro (tipo en mancha), causada por P. teres f. maculata Smedeg. (Ptm). Estas dos formas han sido identificadas como similares morfológicamente, sin embargo, son diferentes a nivel genético y fisiopatológico. Pyrenophora teres f. teres y Pyrenophora teres f. maculata son morfológicamente muy similares, mientras que los síntomas de la enfermedad son diferentes. Estudios filogenéticos moleculares recientes han demostrado que son dos especies o subespecies filogenéticamente distintas, que se consideran poblaciones genéticamente autónomas (Akhavan et al., 2016; Ellwood et al., 2012). La detección de estas formas se ha reportado en Suecia (Jonsson et al., 1997), Francia (Arabi et al., 1992), Australia Occidental (Gupta and Loughman, 2001), Sudáfrica (Louw et al., 1996) y Canadá (Akhavan et al., 2016). Una revisión sobre las dos formas de la enfermedad fue realizada recientemente por Backes et al. (2021).

.

.

- Conidio de Pyrenophora teres. Autor: Francisco Sautua

.

.

.

Síntomas

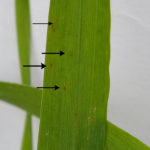

La enfermedad puede aparecer en todas las partes verdes de la planta. El síntoma típico ocurre principalmente en las hojas donde aparecen estrías necróticas longitudinales cruzadas por otras transversales dando la apariencia de mancha en red. Estas manchas son pardo oscuras, generalmente con bordes indefinidos. En las lesiones más viejas el aspecto reticulado es muy evidente. Las espigas también pueden ser atacadas produciendo semillas infectadas. En este caso las semillas se visualizan oscuras, pero no es posible identificar precisamente si se trata de D. teres o B. sorokiniana. Cuando la infección proviene de semilla la primera hoja muestra generalmente, una estría longitudinal necrótica. Puede provocar la muerte precoz de la hoja.

Existen dos formas de Pyrenophora teres similares morfológicamente pero causantes de manchas diferentes: típica mancha reticular o tipo en red, es decir, lesiones necróticas longitudinales y de color marrón oscuro, que puede volverse clorótica (causada por Ptt) y una mancha con lesiones circulares o elípticas de color marrón oscuro con clorosis en los tejidos circundantes (causada por Ptm). Esta última presenta síntomas no reticulado (sin red) sino que por el contrario, son manchas muy similares a los causados por B. sorokiniana y solo pueden distinguirse entre sí por la observación microsópica de los conidios. Ambas formas de D. teres producen compuestos fitotóxicos, denominados marasmines, responsables de los cambios patológicos que siguen a la infección.

.

- Mancha en forma de red (Ptt)

- Mancha en forma de red (Ptt)

.

.

- Mancha en forma spot (Ptm)

- Mancha en forma spot (Ptm)

.

.

Condiciones predisponentes

* La siembra de semillas infectadas introduce la enfermedad en campos nuevos o bajo rotación.

* El monocultivo asegura la presencia indefinida del patógeno en el cultivo. Resulta más grave cuando se trata de siembra directa.

* Temperaturas entre 15- 25Cº y humedad relativa > a 90% en el ciclo de cultivo.

* La posibilidad de infección aumenta con temperaturas templado-cálidas y disminuye con niveles térmicos inferiores.

* Uso de cultivares susceptibles.

.

Daños

Constituye la principal enfermedad de los cultivos de cebada del Cono Sur. Aparece en todas las regiones productoras de nuestro país desde los primeros estadios del cultivo.

Provoca daños de rendimiento estimados en un 20%. Los componentes más afectados son el peso de los granos y el número de granos por metro cuadrado. También disminuye el extracto de malta, lo que afecta la calidad maltera para la producción de cerveza.

.

.

- Síntomas de la mancha en red (MR) de la cebada en Argentina. (a, b, c, d) Elevados niveles de intensidad de la MR de la cebada en lotes con 2 a 3 aplicaciones de fungicida durante la campaña 2021/2022 en la localidad de Balcarce; (e) Colonia de Pyrenophora teres mostrando columnas miceliares; (f) Conidios típicos de P. teres. Autores: Sautua y Carmona, 2023. Fotos: Di Núbila, S.

.

.

Ciclo de la enfermedad y epidemiología

El patógeno ataca exclusivamente a la cebada. En nuestro país aparece en todas las regiones donde se cultiva este cereal y desde los primeros estadios.

Las principales fuentes de inóculo son las semillas infectadas y el rastrojo infestado.D. teres, es un patógeno muy frecuente en semillas y es transmitido con una tasa de transmisión del 21%. La diseminación a grandes distancias ocurre a través de semillas infectadas. El nivel de infección se intensifica con temperaturas crecientes a partir de los 10ºC (rango óptimo 15-25ºC) y períodos de mojado foliar de 12 a 36 horas. El viento puede transportar los conidios a cortas distancias porque las esporas son grandes y pesadas. Las esporas pueden ser diseminadas por el viento y depositadas en hojas de la misma planta o plantas vecinas dentro del cultivo. El hongo penetra por apresorios. El patrón de distribución en el lote es generalizado y uniforme. En rastrojos, el hongo sobrevive saprofíticamente produciendo conidios o ascosporas en peritecios.

En condiciones de laboratorio, las lesiones necróticas pueden aparecer tan pronto como 24 h después de la inoculación y el desarrollo completo de los síntomas y la esporulación pueden ocurrir en una semana después de la inoculación. El área clorótica que rodea la lesión necrótica está libre de crecimiento de hifas fúngicas, lo que es consistente con la liberación de toxinas difusibles durante la infección (Keon y Hargreaves, 1983; Smedegård-Petersen, 1977).

.

.

.

Medidas preferenciales de manejo (económicas y antes de la siembra):

* Tratamiento eficiente de semillas

* Rotación de cultivos

* Ambas deben ser llevadas a cabo complementariamente.

.

Otras:

* Aplicación de fungicidas foliares

* Siembra de cultivares tolerantes

* Eliminación de plantas guachas

.

En Argentina se confirmó la presencia de cepas resistentes a carboxamidas con simple y doble mutación en un solo aislado (Sautua y Carmona, 2023).

.

- Mancha en red en Andreia, Bigand, Sta Fe. Autores: Silvana Di Nubila, Marcelo Carmona

- Mancha en red en Andreia, Bigand, Sta Fe. Autores: Silvana Di Nubila, Marcelo Carmona

- Mancha en Red de la Cebada

- Drechslera teres sobre flores estériles de la Cebada

- Conidios de Drechslera teres sobre semilla de cebada

- Conidios de Drechslera teres sobre semilla de cebada

- Conidios de Drechslera teres sobre semilla de cebada

- Conidios de Drechslera teres

- Conidios de Drechslera teres

- Colonia de Drechslera teres creciendo sobre APG.

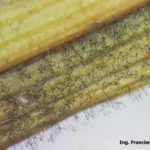

- Esporulación de Drechslera teres en hoja de cebada, variedad Shakira.

- Esporulación (Conidios) de Drechslera teres en hoja de cebada, variedad Shakira.

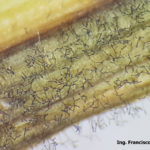

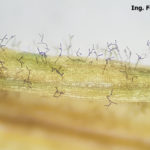

- Conidios en conidióforos libres de Drechslera teres en hoja de cebada, variedad Shakira.

- Conidios de Drechslera teres en hoja de cebada, variedad Shakira.

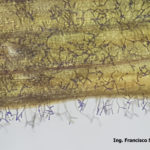

- Conidios de Drechslera teres en hoja de cebada, variedad Shakira.

- Conidios en conidióforos libres de Drechslera teres en hoja de cebada, variedad Shakira.

- Aislamientos de Drechslera teres a partir de hojas de cebada, variedad Shakira, creciendo en V8.

- Conidio de Pyrenophora teres germinando in vitro con dos tubos germinativos. Autor: Francisco Sautua

- Pseudotecio de Pyrenophora teres sobre semilla de cebada. Autores: Dr. Marcelo Carmona y Dr. Francisco Sautua

- Autores: Dr. Marcelo Carmona, Dr. Francisco Sautua

- Autores: Dr. Marcelo Carmona, Dr. Francisco Sautua

- Autores: Dr. Marcelo Carmona, Dr. Francisco Sautua

- Sintomas iniciales de plantas de cebada inoculadas con D. teres

- Sintomas iniciales de plantas de cebada inoculadas con D. teres

- Sintomas avanzados de plantas de cebada inoculadas con D. teres

- 01 D. teres f. maculata, con lesiones circulares o elípticas marrón oscuro (tipo en mancha redonda u oval)

- 02 D. teres f. maculata, con lesiones circulares o elípticas marrón oscuro (tipo en mancha redonda u oval)

- 03 D. teres f. maculata, con lesiones circulares o elípticas marrón oscuro (tipo en mancha redonda u oval)

- 04 D. teres f. maculata, con lesiones circulares o elípticas marrón oscuro (tipo en mancha redonda u oval)

- Síntomas foliares de Mancha en Red. Fontezuela, 2017/2018, variedad Danielle

- Síntomas foliares de Mancha en Red. Fontezuela, 2017/2018, variedad Danielle

- 01 Síntomas foliares iniciales en plantas de cebada variedad Shakira inoculadas con Drechslera teres

- 05 Síntomas foliares iniciales en plantas de cebada variedad Shakira inoculadas con Drechslera teres

- 06 Síntomas foliares iniciales en plantas de cebada variedad Shakira inoculadas con Drechslera teres

- 07 Síntomas foliares iniciales en plantas de cebada variedad Shakira inoculadas con Drechslera teres

- 09 Síntomas foliares típicos en plantas de cebada variedad Shakira inoculadas con Drechslera teres

- 12 Síntomas foliares típicos en plantas de cebada variedad Shakira inoculadas con Drechslera teres

- 13 Síntomas foliares típicos en plantas de cebada variedad Shakira inoculadas con Drechslera teres

- 17 Síntomas foliares típicos en plantas de cebada variedad Shakira inoculadas con Drechslera teres

- 19 Síntomas foliares típicos en plantas de cebada variedad Shakira inoculadas con Drechslera teres

- 20 Síntomas foliares típicos en plantas de cebada variedad Shakira inoculadas con Drechslera teres

.

- 01 Mancha en red causada por Drechslera teres fsp maculata

- 02 Mancha en red causada por Drechslera teres fsp maculata

- 03 Mancha en red causada por Drechslera teres fsp maculata

.

.

.

Notas

Cebada: se confirmó una multiresistencia de mancha en red. 25 de mayo de 2022

.

.

Articulos

Fungicide resistance found in barley spot form of net blotch in Western Australia (Feb. 13, 2018)

.

Bibliografía

Ahmed Lhadj W, Boungab K, Righi Assia F, et al. (2021) Genetic diversity of Pyrenophora teres in Algeria. J Plant Pathol. doi: 10.1007/s42161-021-01010-0

Ariyawansa HA, Kang JC, Alias SA, Chukeatirote E, Hyde KD (2014) Pyrenophora. Mycosphere 5(2): 351–362. doi: 10.5943/mycosphere/5/2/9

Akhavan A, Turkington AK, Askarian H, et al. (2016) Virulence of Pyrenophora teres populations in western Canada. Canadian Journal of Plant Pathology 38(2): 183-196. doi: 10.1080/07060661.2016.1159617

Akhavan A, Strelkov S, Askarian H, et al. (2017) Sensitivity of western Canadian Pyrenophora teres f. teres and P. teres f. maculata isolates to propiconazole and pyraclostrobin. Can. J. Plant Pathol. 39(1): 11-24. doi: 10.1080/07060661.2017.1282541

Backes A, Guerriero G, Ait Barka E, Jacquard C (2021) Pyrenophora teres: Taxonomy, Morphology, Interaction With Barley, and Mode of Control. Front. Plant Sci. 12: 614951. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2021.614951

Barreto D, Carmona M (1993) Microflora of barley and malt in Argentina. Procedings 1st. ISTA Plant Disease Committee Symposium on Seed Health Testing Pp. 70-74. Otawa, Canadá.

Brown MP, Steffeson BJ, Webster RK (1993) Host range of Pyrenophora teres f. teres isolates from California. Plant Disease 77: 942–947. Link

Campbell GF, Crous PW, Lucas JA (1999) Pyrenophora teres f. maculata, the cause of Pyrenophora leaf spot of barley in South Africa. Mycological Research 103: 257-267. doi: 10.1017/S0953756298007114

Carlsen SA, Neupane A, Wyatt NA, et al. (2017) Characterizing the Pyrenophora teres f. maculata–Barley Interaction Using Pathogen Genetics. G3: Genes|Genomes|Genetics. 7(8): 2615-2626. doi: 10.1534/g3.117.043265

Carmona M, López SE, Barreto D (1996) Ocurrencia de los estados teleomórfico y picnidial de Pyrenophora teres en Argentina. Fitopatologia Brasileira 21(3): 394.

Carmona M, Barreto D, Moschini R, Reis EM (2008) Epidemiology and Control of Seed-borne Drechslera teres on Barley. Cereal Research Communications 36: 637–645. doi: 10.1556/CRC.36.2008.4.13

Çelik Oğuz A, Karakaya A (2021) Genetic Diversity of Barley Foliar Fungal Pathogens. Agronomy 11(3): 434. doi: 10.3390/agronomy11030434

Chen H, Xue LH, White JF, et al. (2021) Identification and Characterization of Pyrenophora Species Causing Leaf Spot on Oat (Avena sativa) in Western China. Plant Pathology. doi: 10.1111/ppa.13491

Clare SJ, Wyatt NA, Brueggeman RS, Friesen TL (2020) Research advances in the Pyrenophora teres-barley interaction. Mol Plant Pathol. 21(2): 272-288. doi: 10.1111/mpp.12896

Clare SJ, Duellman KM, Richards JK, et al. (2022) Association mapping reveals a reciprocal virulence/avirulence locus within diverse US Pyrenophora teres f. maculata isolates. BMC Genomics 23: 285. doi: 10.1186/s12864-022-08529-1

Dahanayaka BA, Vaghefi N, Knight NL, et al. (2021) Population structure of Pyrenophora teres f. teres barley pathogens from different continents. Phytopathology. doi: 10.1094/PHYTO-09-20-0390-R

Dahanayaka BA, Vaghefi N, Snyman L, Anke M (2021) Investigating in vitro mating preference between or within the two forms of Pyrenophora teres and its hybrids. Phytopathology. doi: 10.1094/PHYTO-02-21-0058-R

Dahanayaka BA, Snyman L, Vaghefi N, Martin A (2022) Using a Hybrid Mapping Population to Identify Genomic Regions of Pyrenophora teres Associated With Virulence. Front. Plant Sci. 13: 925107. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2022.925107

, , Sexual recombination and genetic diversity in Iranian populations of Pyrenophora teres. J Phytopathol 169: 447– 460. doi: 10.1111/jph.13001

Dokhanchi H, Arzanlou M, Abed-Ashtiani F (2021) First occurrence of Pyrenophora semeniperda a new pathogen on barley in Iran. Cereal Research Communications. doi: 10.1007/s42976-021-00149-x

Duczek LJ, Sutherland KA, Reed SL, et al. (1999) Survival of leaf spot pathogens on crop residues of wheat and barley in Saskatchewan. Canadian Journal of Plant Pathology 21: 165-173. doi: 10.1080/07060669909501208

Dutilloy E, Oni FE, Esmaeel Q, et al. (2022) Plant Beneficial Bacteria as Bioprotectants against Wheat and Barley Diseases. Journal of Fungi. 8(6): 632. doi: 10.3390/jof8060632

El-Mor IM, Fowler RA, Platz GJ, et al. (2018) An Improved Detached-Leaf Assay for Phenotyping Net Blotch of Barley Caused by Pyrenophora teres. Plant Dis. 102(4): 760-763. doi: 10.1094/PDIS-07-17-0980-RE

Ellwood SR, Liu Z, Syme RA, et al. (2010) A first genome assembly of the barley fungal pathogen Pyrenophora teres f. teres. Genome Biol 11, R109. doi: 10.1186/gb-2010-11-11-r109

Ellwood SR, Syme RA, Moffat CS, Oliver RP (2012) Evolution of three Pyrenophora cereal pathogens: recent divergence, speciation and evolution of non-coding DNA. Fungal Genetics and Biology 49(10): 825-829. doi: 10.1016/j.fgb.2012.07.003

Ellwood SR, Piscetek V, Mair WJ, et al. (2019) Genetic variation of Pyrenophora teres f. teres isolates in Western Australia and emergence of a Cyp51A fungicide resistance mutation. Plant Pathology 68: 135-142. https://doi.org/10.1111/ppa.12924

Ficsor A, Bakonyi J, Tóth B, et al. (2010) First Report of Spot Form of Net Blotch of Barley Caused by Pyrenophora teres f. maculata in Hungary. Plant Disease 94: 1062-1062. doi: 10.1094/PDIS-94-8-1062C

Friesen TL, Faris JD, Solomon PS, Oliver RP (2008) Host-specific toxins: effectors of necrotrophic pathogenicity. Cell Microbiol. 10(7): 1421-8. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2008.01153.x

Gamba FM, Šišić A, Finckh MR (2021) Continuous variation and specific interactions in the Pyrenophora teres f. teres–barley pathosystem in Uruguay. J Plant Dis Prot 128: 421–429. doi: 10.1007/s41348-020-00386-y

Grewal TS, Rossnagel BG, Pozniak CJ, et al. (2008) Mapping quantitative trait loci associated with barley net blotch resistance. Theor Appl Genet 116: 529–539. doi: 10.1007/s00122-007-0688-9

Helps J, Lopez-Ruiz F, Zerihun A, van den Bosch F (2024) Do Growers Using Solo Fungicides Affect the Durability of Disease Control of Growers Using Mixtures and Alternations? The Case of Spot-Form Net Blotch in Western Australia. Phytopathology 114(3): 590-602. doi: 10.1094/PHYTO-02-23-0050-R

Hodgson LM, Cox BA, Lopez-Ruiz FJ, et al. (2023) Optimized Sample Processing Pipeline for PCR-Based Fungicide Resistance Quantification of Stubble-Borne Fungal Pathogens. Phytopathology 113(2): 321-333. doi: 10.1094/PHYTO-07-22-0239-R

Hodgson LM, Lopez-Ruiz FJ, Gibberd MR, et al. (2025) Field-Scale Gene Flow of Fungicide Resistance in Pyrenophora teres f. teres and the Effect of Selection Pressure on the Population Structure. Phytopathology 115(1): 85-96. doi: 10.1094/PHYTO-10-23-0378-KC

Hoffmeister M, Mehl A, Hinson A, et al. (2022) Acquired QoI resistance in Pyrenophora teres through an interspecific partial gene transfer by Pyrenophora tritici-repentis?. J Plant Dis Prot. 10.1007/s41348-022-00631-6

(1983) A cytological study of the net blotch disease of barley caused by Pyrenophora teres. Physiol. Plant Pathol. 22: 321–329. doi: 10.1016/S0048-4059(83)81019-4

Khaledi N, Zare L, Hassani F, et al. (2024) Comparison of diagnostic methods, virulence and aggressiveness analysis of Pyrenophora spp. in pre-basic seeds in the barley fields. Trop. plant pathol. doi: 10.1007/s40858-023-00631-3

Khan TN, Tekauz A (1982) Occurrence and Pathogenicity of Drechslera teres Isolates Causing Spot-type Symptoms on Barley in Western Australia. Plant Disease 66: 423-425. doi: 10.1094/PD-66-423

Knight NL, Adhikari KC, Dodhia KN, et al. (2024) Workflows for detecting fungicide resistance in net form and spot form net blotch pathogens. Pest Manag Sci. 80: 2131-2140. doi: 10.1002/ps.7951

Lammari HI, Rehfus A, Stammler G, Benslimane H (2020) Sensitivity of the Pyrenophora teres Population in Algeria to Quinone outside Inhibitors, Succinate Dehydrogenase Inhibitors and Demethylation Inhibitors. The Plant Pathology Journal 36: 218-230. doi: 10.5423/PPJ.OA.09.2019.0237

Lammari HI, Rehfus A, Stammler G, et al. (2020) Occurrence and frequency of spot form and net form of net blotch disease of barley in Algeria. J Plant Dis Prot 127: 35–42. doi: 10.1007/s41348-019-00278-w

Lartey RT, Caesar-TonThat TC, Caesar AJ, et al. (2013) First Report of Spot Form Net Blotch Caused by Pyrenophora teres f. maculata on Barley in the Mon-Dak Area of the United States. Plant Disease 97(1): 143. doi: 10.1094/PDIS-07-12-0657-PDN

Leisova L, Kucera L, Minarikova V, (2005) AFLP-based PCR markers that differentiate spot and net forms of Pyrenophora teres. Plant Pathology 54: 66-73. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3059.2005.01117.x

Li J, Wyatt NA, Skiba RM, et al. (2023) Pathogen genetics identifies avirulence/virulence loci associated with barley chromosome 6H resistance in the Pyrenophora teres f. teres – barley interaction. bioRxiv 2023.02.10.527674. doi: 10.1101/2023.02.10.527674

Li J, Wyatt NA, Skiba RM, et al. (2024) Variability in Chromosome 1 of Select Moroccan Pyrenophora teres f. teres Isolates Overcomes a Highly Effective Barley Chromosome 6H Source of Resistance. Mol Plant Microbe Interact. 37(9): 676-687. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-10-23-0159-R

Lightfoot DJ, Able AJ (2010) Growth of Pyrenophora teres in planta during barley net blotch disease. Australasian Plant Pathology 39: 499–507. doi: 10.1071/AP10121

Linde CC, Smith LM, Peakall R (2016) Weeds, as ancillary hosts, pose disproportionate risk for virulent pathogen transfer to crops. BMC Evol Biol 16: 101. doi: 10.1186/s12862-016-0680-6

Linde CC, Smith LM (2019) Host specialisation and disparate evolution of Pyrenophora teres f. teres on barley and barley grass. BMC Evol Biol 19: 139. doi: 10.1186/s12862-019-1446-8

Liu ZH, Friesen TL (2010) Identification of Pyrenophora teres f. maculata, Causal Agent of Spot Type Net Blotch of Barley in North Dakota. Plant Disease 94(4):480. doi: 10.1094/PDIS-94-4-0480A

Liu Z, Ellwood SR, Oliver RP, Friesen TL (2011) Pyrenophora teres: profile of an increasingly damaging barley pathogen. Molecular Plant Pathology 12: 1–19. doi: 10.1111/j.1364-3703.2010.00649.x

Liu ZH, Zhong S, Stasko AK, et al. (2012) Virulence profile and genetic structure of a North Dakota population of Pyrenophora teres f. teres, the causal agent of net form net blotch of barley. Phytopathology 102: 539-546. doi: 10.1094/PHYTO-09-11-0243

Lu S, Platz GJ, Edwards MC, Friesen TL (2010) Mating type locus-specific polymerase chain reaction markers for differentiation of Pyrenophora teres f. teres and P. teres f. maculata, the causal agents of barley net blotch. Phytopathology 100(12): 1298-306. doi: 10.1094/PHYTO-05-10-0135

Mair WJ, Deng W, Mullins JGL, et al. (2016) Demethylase Inhibitor Fungicide Resistance in Pyrenophora teres f. sp. teres Associated with Target Site Modification and Inducible Overexpression of Cyp51. Front. Microbiol. 7: 1279. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2016.01279

Mair WJ, Thomas GJ, Dodhia K, et al. (2020) Parallel evolution of multiple mechanisms for demethylase inhibitor fungicide resistance in the barley pathogen Pyrenophora teres f. sp. maculata. Fungal Genetics and Biology 145: 103475. doi: 10.1016/j.fgb.2020.103475

Mair WJ, Wallwork H, Garrard TA, et al. (2023) Emergence of resistance to succinate dehydrogenase inhibitor fungicides in Pyrenophora teres f. teres and P. teres f. maculata in Australia. bioRxiv 2023.04.23.537974; doi: 10.1101/2023.04.23.537974

Marshall JM, Kinzer K, Brueggeman RS (2015) First Report of Pyrenophora teres f. maculata the Cause of Spot Form Net Blotch of Barley in Idaho. Plant Disease 99(12): 1860. doi: 10.1094/PDIS-03-15-0349-PDN

Martin A, Moolhuijzen P, Tao Y, et al. (2020) Genomic Regions Associated with Virulence in Pyrenophora teres f. teres Identified by Genome-Wide Association Analysis and Biparental Mapping. Phytopathology 110(4): 881-891. doi: 10.1094/PHYTO-10-19-0372-R

Masi M, Zorrilla JG, Meyer S (2022) Bioactive Metabolite Production in the Genus Pyrenophora (Pleosporaceae, Pleosporales). Toxins (Basel) 14(9): 588. doi: 10.3390/toxins14090588

Matzen N, Weigand S, Bataille C, et al. (2024) EuroBarley: control of leaf diseases in barley across Europe. J Plant Dis Prot. doi: 10.1007/s41348-023-00852-3

McLean MS, Howlett BJ, Hollaway GJ (2009) Epidemiology and control of spot form of net blotch (Pyrenophora teres f. maculata) of barley: A review. Crop and Pasture Science 60(4): 303-315. doi: 10.1071/CP08173

McLean MS, Howlett BJ, Hollaway GJ (2009) Erratum to: Epidemiology and control of spot form of net blotch (Pyrenophora teres f. maculata) of barley: A review. Crop and Pasture Science 60: 499–499. doi: 10.1071/CP08173_ER.

McLean MS, Howlett BJ, Hollaway GJ (2010) Spot form of net blotch, caused by Pyrenophora teres f. maculata, is the most prevalent foliar disease of barley in Victoria, Australia. Australasian Plant Pathology 39: 46. doi: 10.1071/AP09054

McLean MS, Keiper FJ, Hollaway GJ (2010) Genetic and pathogenic diversity in Pyrenophora teres f. maculata in barley crops of Victoria, Australia. Australasian Plant Pathology 39(4): 319-325. doi: 10.1071/AP09097

McLean MS, Martin A, Gupta S, et al. (2014) Validation of a new spot form of net blotch differential set and evidence for hybridisation between the spot and net forms of net blotch in Australia. Australasian Plant Pathology 43: 223. doi: 10.1007/s13313-014-0285-8

McLean MS, Poole N, Munoz Santa I, Hollaway GJ (2022) Efficacy of spot form of net blotch suppression in barley from seed, fertiliser and foliar applied fungicides. Crop Protection 153: 105865. doi: 10.1016/j.cropro.2021.105865

Mejía C, Sautua F, Carmona M (2024) Sensitivity of Argentine Pyrenophora teres f. teres isolates to different fungicide mixtures. Archives of Phytopathology and Plant Protection. doi: 10.1080/03235408.2024.2350719

Moolhuijzen P, Lawrence J, Ellwood SR (2021) Potentiators of disease during barley infection by Pyrenophora teres f. teres in a susceptible interaction. Mol Plant Microbe Interact. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-10-20-0297-R

Moya P, Barrera V, Cipollone J, Bedoya C, Kohan L, Toledo A, Sisterna M (2020) New isolates of Trichoderma spp. as biocontrol and plant growth–promoting agents in the pathosystem Pyrenophora teres-barley in Argentina. Biological Control 141: 104152. doi: 10.1016/j.biocontrol.2019.104152

Moya PA, Girotti JR, Toledo AV, Sisterna MN (2018) Antifungal activity of Trichoderma VOCs against Pyrenophora teres, the causal agent of barley net blotch. Journal of Plant Protection Research 58(1): 45–53. doi: 10.24425/119115

Muria-Gonzalez MJ, Zulak KG, Allegaert E, et al. (2020) Profile of the in vitro secretome of the barley net blotch fungus, Pyrenophora teres f. teres. Physiological and Molecular Plant Pathology 109: 101451. doi: 10.1016/j.pmpp.2019.101451

Muria-Gonzalez MJ, Lawrence JA, Palmiero E, et al. (2023) Major Susceptibility Gene Epistasis over Minor Gene Resistance to Spot Form Net Blotch in a Commercial Barley Cultivar. Phytopathology 113(6): 1058-1065. doi: 10.1094/PHYTO-10-22-0376-R

Murray GM, Brennan JP (2010) Estimating disease losses to the Australian barley industry. Aust. Plant Pathol. 39: 85–96. doi: 10.1071/AP09064

Neupane A, Tamang P, Brueggeman RS, Friesen TL (2015) Evaluation of a barley core collection for spot form net blotch reaction reveals distinct genotype-specific pathogen virulence and host susceptibility. Phytopathology 105(4): 509-517. doi: 10.1094/PHYTO-04-14-0107-R

Pereyra SA, Germán SE (2004) First Report of Spot Type of Barley Net Blotch Caused by Pyrenophora teres f. sp. maculata in Uruguay. Plant Disease 88(10): 1162. doi: 10.1094/PDIS.2004.88.10.1162C

Poudel B, Ellwood SR, Testa AC, et al. (2017) Rare Pyrenophora teres Hybridization Events Revealed by Development of Sequence-Specific PCR Markers. Phytopathology 107(7): 878-884. doi: 10.1094/PHYTO-11-16-0396-R

Poudel B, McLean MS, Platz GJ, et al. (2018) Investigating hybridisation between the forms of Pyrenophora teres based on Australian barley field experiments and cultural collections. European Journal of Plant Pathology 1–9. doi: 10.1007/s10658-018-1574-9

Pütsepp R, Mäe A, Põllumaa L, et al. (2024) Fungicide Sensitivity Profile of Pyrenophora teres f. teres in Field Population. Journal of Fungi. 10(4): 260. doi: 10.3390/jof10040260

Rehfus A, Miessner S, Achenbach J, et al. (2016) Emergence of succinate dehydrogenase inhibitor resistance of Pyrenophora teres in Europe. Pest. Manag. Sci., 72: 1977-1988. doi: 10.1002/ps.4244

Reis E (1991) Mancha en red de la cebada: Biología, epidemiología y control de Drechslera teres. Instituto Nacional de Investigación Agropecuaria. Serie Técnica Nº3. Pp 8-10. Link

Retman S, Melnichuk F, Kyslykh T, Shevchuk O (2022) Complex of Barley Leaf Spots in Ukraine. Chemistry Proceedings 10(1):1. doi: 10.3390/IOCAG2022-12290

Ronen M, Sela H, Fridman E, et al. (2019) Characterization of the Barley Net Blotch Pathosystem at the Center of Origin of Host and Pathogen. Pathogens 8(4): 275. doi: 10.3390/pathogens8040275

Sarpeleh A, Wallwork H, Catcheside DEA, et al. (2007) Proteinaceous metabolites from Pyrenophora teres contribute to symptom development of barley net blotch. Phytopathology 97(8): 907–915. doi: 10.1094/PHYTO-97-8-0907

Sautua FJ, Carmona MA (2023) SDHI resistance in Pyrenophora teres f teres and molecular detection of novel double mutations in sdh genes confering high resistance. Pest Manag Sci. doi: 10.1002/ps.7517

Scott DB (1991) Identity of Pyrenophora isolates causing net-type and spot-type lesions on barley. Mycopathologia 116: 29–35. doi: 10.1007/BF00436087

Semar M, Strobel D, Koch A, et al. (2007) Field efficacy of pyraclostrobin against populations of Pyrenophora teres containing the F129L mutation in the cytochrome b gene. J Plant Dis Prot 114: 117–119. doi: 10.1007/BF03356718

Shipton WA, Khan TN, Boyd WJR (1973) Net blotch of barley. Rev. Plant Pathol. 52: 269–290.

Sierotzki H, Frey R, Wullschleger J, et al. (2007) Cytochrome b gene sequence and structure of Pyrenophora teres and P. tritici-repentis and implications for QoI resistance. Pest Management Science 63: 225–233. doi: 10.1002/ps.1330

Smedegard-Petersen V (1971) Pyrenophora teres f. teres and Pyrenophora teres f. maculata on barley in Denmark. Arskrift den kgle Vet-Landbohojsk 971: 124–144.

Smedegård-Petersen V (1976) Pathogenesis and genetics of net-spot blotch and leaf stripe of barley caused by Pyrenophora teres and Pyrenophora graminea, Link

(1977) Isolation of two toxins produced by Pyrenophora teres and their significance in disease development of net‐spot blotch of barley. Physiol. Plant Pathol. 10, 203–211. doi: 10.1016/0048-4059(77)90024-8

Suemoto H, Matsuzaki Y, Iwahashi F (2019) Metyltetraprole, a novel putative complex III inhibitor, targets known QoI-resistant strains of Zymoseptoria tritici and Pyrenophora teres. Pest Management Science 75: 1181-1189. doi: 10.1002/ps.5288

Syme RA, Martin A, Wyatt NA, et al. (2018) Transposable Element Genomic Fissuring in Pyrenophora teres Is Associated With Genome Expansion and Dynamics of Host–Pathogen Genetic Interactions. Front. Genet. 9: 130. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2018.00130

Tamang P, Richards JK, Solanki S, et al. (2021) The Barley HvWRKY6 Transcription Factor Is Required for Resistance Against Pyrenophora teres f. teres. Front. Genet. 11: 601500. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2020.601500

Tini F, Covarelli L, Ricci G, et al. (2022) Management of Pyrenophora teres f. teres, the Causal Agent of Net Form Net Blotch of Barley, in A Two-Year Field Experiment in Central Italy. Pathogens 11(3): 291. doi: 10.3390/pathogens11030291

Tekauz A (1985) A numerical scale to classify reactions of barley to Pyrenophora teres. Can. J. Plant Pathol. 7: 181–183. doi: 10.1080/07060668509501499

Turo C, Mair W, Martin A, et al., (2021) Species hybridisation and clonal expansion as a new fungicide resistance evolutionary mechanism in Pyrenophora teres spp. bioRxiv 2021.07.30.454422; doi: 10.1101/2021.07.30.454422

Uranga JP, Perelló AE, Schierenbeck M, et al. (2021) First screening for resistance in Argentinian cultivars against Pyrenophora teres f. maculata, a recently reported pathogen in wheat. Eur J Plant Pathol. doi: 10.1007/s10658-021-02328-2

, , , et al. (2021) Population genetic structure of four regional populations of the barley pathogen Pyrenophora teres f. maculata in Iran is characterized by high genetic diversity and sexual recombination. Plant Pathol. 70: 735– 744. doi: 10.1111/ppa.13326

Vasighzadeh A, Sharifnabi B, Javan-Nikkhah M, et al. (2022) Infection experiments of Pyrenophora teres f. maculata on cultivated and wild barley indicate absence of host specificity. Eur J Plant Pathol. doi: 10.1007/s10658-022-02496-9

Volkova G, Yakhnik Y (2022) Pyrenophora teres: Population structure, virulence and aggressiveness in Southern Russia. Saudi Journal of Biological Sciences 29: 103401. doi: 10.1016/j.sjbs.2022.103401

Walters DR, Avrova A, Bingham IJ, et al. (2012) Control of foliar diseases in barley: towards an integrated approach. Eur J Plant Pathol 133: 33–73. doi: 10.1007/s10658-012-9948-x

Williams KJ, Lichon A, Gianquitto P, et al. (1999) Identification and mapping of a gene conferring resistance to the spot form of net blotch (Pyrenophora teres f maculata) in barley. Theor. Appl. Genet. 99: 323–327. doi: 10.1007/s001220051239

Wyatt NA, Richards JK, Brueggeman RS, Friesen TL (2020) A Comparative Genomic Analysis of the Barley Pathogen Pyrenophora teres f. teres Identifies Subtelomeric Regions as Drivers of Virulence. Mol Plant Microbe Interact. 33: 173-188. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-05-19-0128-R

Wyatt NA, Friesen TL (2021) Four Reference Quality Genome Assemblies of Pyrenophora teres f. maculata: A Resource for Studying the Barley Spot Form Net Blotch Interaction. Mol Plant Microbe Interact. 34(1): 135-139. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-08-20-0228-A

Yun SJ, Gyenis L, Hayes PM (2005) Quantitative trait loci for multiple disease resistance in wild barley. Crop Sci. 45: 2563–2572. doi: 10.2135/cropsci2005.0236

Youcef-Benkada M, Bendahmane B, Barrault S, Albertini L (1994) Effects of inoculation of barley inflorescences with Drechslera teres upon the location of seed-borne inoculum and its transmission to seedlings as modified by temperature and soil moisture. Plant Pathol. 43: 350-355.

.