.

Condición fitosanitaria: Presente

Grupo de cultivos: Oleaginosas

Especie hospedante: Girasol (Helianthus annuus L.)

Rango de hospedantes: amplio, no específico. Además del girasol, provoca importantes pérdidas de rendimiento en alcaucil o alcachofa (Cynara cardunculus L. var. scolymus), coliflor (Brassica oleracea var. botrytis L.), algodón (Gossypium hirsutum L.), berengena (Solanum melongena L.), lechuga (Lactuca sativa L.), olivo (Olea europaea L.), papa (Solanum tuberosum L.), tabaco (Nicotiana tabacum L.), y tomate (Solanum lycopersicum L.), entre otros (Pegg y Brady, 2002). (**)

Epidemiología: monocíclica, subaguda

Etiología: Hongo. Necrotrófico

Agente causal: Verticillium dahliae Klebahn (1913)

Taxonomía: Eukaryota > Fungi > Dikarya > Ascomycota > Pezizomycotina > Sordariomycetes > Hypocreomycetidae > Glomerellales > Plectosphaerellaceae > Verticillium

El género Verticillium sensu stricto corresponde a un grupo monofilético de taxa compuesto por V. dahliae que se ha conservado como el Verticillium tipo (Inderbitzin et al., 2011).

Verticillium se coloca en la familia Plectosphaerellaceae (Zare et al., 2007) que está estrechamente relacionada con Colletotrichum en las Glomerellaceae (Zhang et al., 2006), otro importante grupo de patógenos de plantas. Tanto Plectosphaerellaceae como Glomerellaceae son familias de posición filogenética incierta dentro de la subclase Hypocreomycetidae.

.

(**) La especialización de V. dahliae de acuerdo con el hospedante puede ocurrir, lo que significa que los aislados de un hospedante dado pueden ser patógenos en otros hospedadores pero, en general, son más virulentos (los síntomas son más severos) en los hospedantes de los que se obtuvieron. En algunos aislados de V. dahliae, la especialización por el hospedante es más pronunciada (Bhat y Subbarao, 1999; Douhan y Johnson, 2001).

.

.

.

.

Antecedentes

Esta enfermedad ha sido históricamente importante en Argentina y Estados Unidos (Gulya et al., 1997; Radi y Gulya, 2007; Galella et al., 2012), así como en países templados de Europa (Harveson y Markell , 2016).

.

Sintomatología

La enfermedad suele expresarse a partir de floración, siendo menos frecuentes los ataques en etapas vegetativas. El primer síntoma es una clorosis internerval, generalmente situada de un solo lado de la nervadura principal. El centro de la mancha se necrosa rápidamente, representando uno de los síntomas más comunes, el abigarrado de la hoja. Los tejidos adquieren un color castaño y mueren, y la hoja finalmente se seca completamente. Todas las hojas alimentadas por el mismo sector de la corteza presentan los mismos síntomas a lo largo del tallo. El tallo se ennegrece desde la base, debido al avance del hongo que se instaló desde las raíces. A lo largo del tallo aparecen los microesclerocios sobre la epidermis. Otros síntomas asociados a la enfermedad son el encrespamiento y reducción del área foliar (al reducirse la expansión foliar), y la disminución en altura y diámetro del capítulo de plantas severamente dañadas. Las plantas enfermas sufren marchites prematura, con tallos débiles (propensos a quebrarse) y capítulos inclinados con frutos vanos en el centro.

.

- Autor: Howard F. Schwartz, Colorado State University, Bugwood.org

- Autor: Alexander von Humboldt

- Hoja de girasol con clorosis y necrosis intervenal causada por la marchitez por Verticillium. Autores: Radi S, Gulya T, USDA ND.

- Marchitez foliar causada por la infección por Verticillium. Autores: Radi S, Gulya T, USDA ND.

.

.

.

Variabilidad genética

Todos los aislamientos evaluados de Francia, Italia, España, Argentina y Ucrania se asignaron al grupo de compatibilidad vegetativa (VCG) 2B (García-Carneros et al., 2014; Martín-Sanz et al., 2018). En Bulgaria, Turquía, Rumania y Ucrania, algunos aislamientos se asignaron a VCG6, pero otros no se pudieron asignar a ningún VCG.

La primera raza (NA-1) se detectó en los Estados Unidos y fue controlada por la resistencia en HA 89, que estaba asociada a un solo gen principal o mayor (R) (Fick y Zimmer, 1974; Gulya et al., 1997). Posteriormente, sobre la base de la caracterización fenotípica, se han reportado nuevas razas que quebraron esta resistencia, aparentemente diferentes entre sí, en base a la caracterización fenotípica: NA-Vd2 en Estados Unidos (Gulya, 2007), y cuatro en Argentina (Bertero de Romano y Vázquez, 1982; Galella et al., 2004; Clemente et al., 2017) y uno en España (García-Ruiz et al., 2014). En Argentina se ha reportado la presencia de cuatro razas patógenas sobre la base del uso de un conjunto de diferenciales que no es público (Clemente et al., 2017). En Europa se han identificado hasta 3 razas del patógeno: V1, V2-EE (Europa del Este) y V2-WE (Europa Occidental) (Martín-Sanz et al., 2018). Este último estudio, realizados por investigadores de España, determinó que la raza V2-WE presente en Argentina (VdS0112) superando V1 (HA 89) (Bertero de Romano y Vázquez, 1982; Galella et al., 2004), también está presente en España, Francia e Ucrania.

La herencia de la resistencia a la raza NA-Vd2 parece ser recesiva o aditiva en algunas líneas, y en Argentina se está explorando la introducción de resistencia cuantitativa piramidal (Galella et al., 2012).

.

Epidemiología

Los microesclerocios liberados al suelo por la descomposición de los restos de cosecha (hongo necrotrófico) le permiten sobrevivir en él por varios años. El patógeno también se puede propagar por conidios adheridos a la semilla. Las especies de Verticillium se reproducen sólo asexualmente, no se conoce ningún estado sexual (Usami et al., 2009). El hongo es potencialmente heterotálico ya que varios aislados contienen el idiomorfo MAT1-1 o MAT1-2 (Usami et al., 2009).

La infección de la planta se da a través de las raicillas o puntas de las raíces. El hongo alcanza los haces xilemáticos y luego se distribuye en forma sistémica por toda la planta. Se conocen algunos mecanismos involucrados en la resistencia o tolerancia de esta enfermedad: cambios anatómicos de los elementos conductores con la formación de sustancias ocluyentes, y cambios fisiológicos que afectan la producción o germinación de esporas.

.

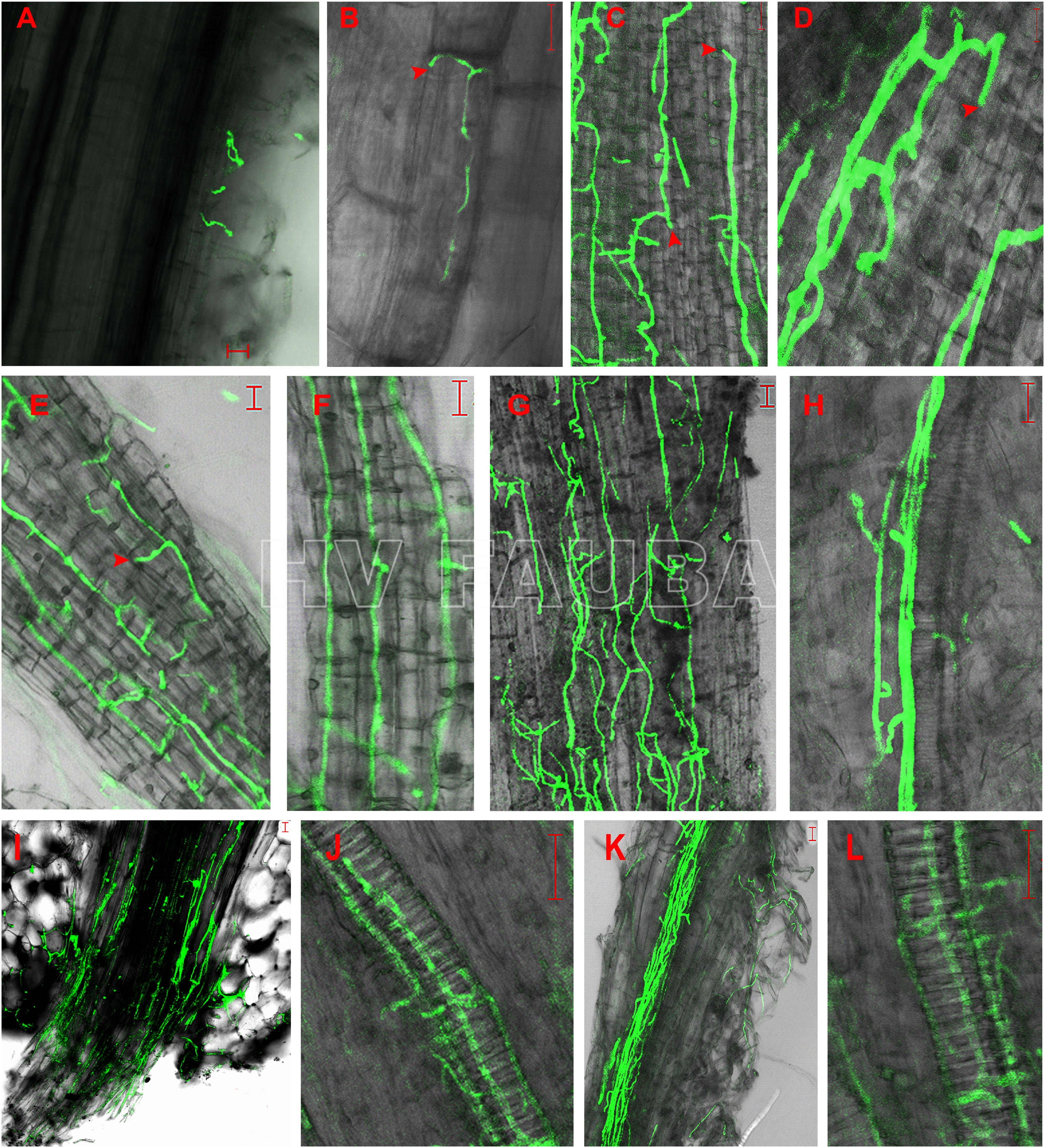

- Germinación de conidios de un aislado de Verticillium dahliae expresando la proteína verde fluorescente (GFP) y colonización del sistema radicular de plántulas de girasol desde 24 h hasta 7 días postinoculación. A: Conidios germinados en pelos radicales 24 h postinoculación (hpi). B: Micelio extendido a lo largo de la unión longitudinal entre las células epidérmicas de la raíz en la zona de elongación de la raíz lateral 48 hpi. C y D: el micelio continuó alargándose a lo largo del eje longitudinal de las células epidérmicas de la raíz y el micelio penetró directamente en la célula epidérmica adyacente sin formar ninguna estructura de infección visible, como apresorios, respectivamente, 72 hpi. E y F: redes de micelio formadas en la superficie de las raíces laterales 96 hpi. G: Micelio formado desordenadamente en la superficie de la raíz primaria 96 hpi. H: Sin colonización de los vasos vasculares de la raíz lateral 96 hpi. I: Colonización masiva de micelio en el sitio de unión de la raíz lateral y la raíz primaria 96 hpi. J: Micelio en vaso vascular de la raíz lateral 5 días después de la inoculación (dpi). K: micelio extendido a lo largo del haz vascular de la raíz primaria 7 dpi. L: Desarrollo de V. dahliae en células vasculares de la raíz primaria 7 dpi. Análisis de imágenes capturadas mediante microscopía de barrido láser (LSM). Las flechas indican los sitios de penetración. Barras de escala = 20 µm. Autor: Zhang et al., 2018.

.

Las Medidas de Manejo Integrado de la enfermedad incluyen

* Siembra de híbridos de girasol resistente o tolerantes a V. dahliae. Es la herramienta más efectiva para manejar esta enfermedad. Es conveniente consultar las publicaciones anuales de comportamiento de híbridos RED INTA-ASAGIR / Red Nacional de cultivares de girasol (ej. Campaña 2019- 2020), en donde el INTA evalúa el comportamiento de los híbridos frente a marchitez por Verticillium.

* Historia del lote: evitar lotes con historia de la enfermedad.

* Rotaciones largas con cultivos no hospedantes (gramíneas).

* Nutrición balanceada (N).

* La permanencia del rastrojo en superficie (siembra directa) disminuye la densidad de microesclerocios en suelo y por ende puede disminuir la enfermedad.

.

.

.

Bibliografía

Bhat RG, Subbarao KV (1999) Host range specificity in Verticillium dahliae. Phytopathology 89: 1218–1225. doi: 10.1094/PHYTO.1999.89.12.1218

Bhattacharya D, Dhar TK, Ali E (1992) An enzyme immunoassay of phaseolinone and its application in estimation of the amount of toxin in Macrophomina phaseolina-infected seeds. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 58: 1970-1974. doi: 10.1128/aem.58.6.1970-1974.1992

Bhattacharya D, Dhar TK, Siddiqui KAI, Ali E (1994) Inhibition of seed germination by Macrophomina phaseolina is related to phaseolinone production. Journal of Applied Bacteriology 77: 129–133. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.1994.tb03055.x

Bautista-Jalon LS, Frenkel O, Tsror L, et al. (2020) Genetic differentiation of Verticillium dahliae populations recovered from symptomatic and asymptomatic hosts. Phytopathology 111(1):149-159. doi: 10.1094/PHYTO-06-20-0230-FI

Ben C, Toueni M, Montanari S, et al. (2013) Natural diversity in the model legume Medicago truncatula allows identifying distinct genetic mechanisms conferring partial resistance to Verticillium wilt. J Exp Bot. 64(1): 317–332. doi: 10.1093/jxb/ers337

Biessy A, Novinscak A, St-Onge R, et al. (2021) Inhibition of Three Potato Pathogens by Phenazine-Producing Pseudomonas spp. Is Associated with Multiple Biocontrol-Related Traits. mSphere 6(3): e0042721. doi: 10.1128/mSphere.00427-21

Carrero‐Carrón I, Rubio MB, Niño‐Sánchez J, et al. (2018) Interactions between Trichoderma harzianum and defoliating Verticillium dahliae in resistant and susceptible wild olive clones. Plant Pathol. doi: 10.1111/ppa.12879

Chen JY, Zhang DD, Huang JQ, et al. (2020) Genome Sequence of Verticillium dahliae Race 1 Isolate VdLs.16 From Lettuce. Mol Plant Microbe Interact. 33(11): 1265-1269. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-04-20-0103-A

Clemente GE, Bazzalo ME, Escande AR (2017) New variants of Verticillium dahliae causing sunflower leaf mottle and wilt in Argentina. J. Plant Pathol. 99: 445–451. doi: 10.4454/jpp.v99i2.3875

Daayf F (2014) Verticillium wilts in crop plants: Pathogen invasion and host defense responses. Canadian Journal of Plant Pathology 37(1): 8-20. doi: 10.1080/07060661.2014.989908

Dhar TK, Siddiqui KAI, Ali E (1982) Structure of phaseolinone, a novel phytotoxin from Macrophomina phaseolina. Tetrahedron Letters 23: 5459-5462. doi: 10.1016/0040-4039(82)80157-3

Douhan LI, Johnson DA (2001) Vegetative compatibility and pathogenicity of Verticillium dahliae from spearmint and peppermint. Plant Disease 85: 297–302. doi: 10.1094/PDIS.2001.85.3.297

Fick GN, Zimmer DE (1974) Monogenic resistance to Verticillium wilt in sunflowers. Crop Sci. 14: 895. doi: 10.2135/cropsci1974.0011183X001400060037x

Fousia S, Tsafouros A, Roussos PA, Tjamos SE (2018) Increased resistance to Verticillium dahliae in Arabidopsis plants defective in auxin signalling. Plant Pathology. doi: 10.1111/ppa.12881

Galella MT, Bazzalo ME, Morata M, et al. (2012) “Pyramiding QTLs for Verticillium dahliae resistance”. En: Proceedings of the 18th International Sunflower Conference, Mar del Plata, 219–224. Link

Galella MT, Bazzalo ME, León A (2004) “Compared pathogenicity of Verticillium dahlia isolates from Argentine and the USA”. En: Proceedings of the 16th International Sunflower Conference, Fargo, ND, 177–180.

García-Carneros AB, García-Ruiz R, Molinero-Ruiz L (2014) Genetic and molecular approach to Verticillium dahliae infecting sunflower. Helia 37: 205–214. doi: 10.1515/helia-2014-0014

Gkizi D, Lehmann S, Haridon FL, Serrano M, Paplomatas EJ, Métraux JP, Tjamos SE (2016) The Innate Immune Signaling System as a Regulator of Disease Resistance and Induced Systemic Resistance Activity Against Verticillium dahliae. Molecular Plant-Microbe Interactions 29(4): 313-323. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-11-15-0261-R

Gulya TJ, Rashid KY, Marisevic SM (1997) “Sunflower diseases,” in Sunflower Technology and Production, ed. A. A. Schneiter (Madison, WI: ASA), 263–380. doi: 10.2134/agronmonogr35.c6

Harveson RM, Markell SG (2016) “Verticillium wilt,” in Compendium of Sunflower Diseases, eds R. M. Harveson, S. G. Markell, C. C. Block and T. J. Gulya (St. Paul, MN: The American Phytopathological Society),59–61.

Inderbitzin P, Bostock RM, Davis RM, et al. (2011) Phylogenetics and Taxonomy of the Fungal Vascular Wilt Pathogen Verticillium, with the Descriptions of Five New Species. PLoS ONE 6(12): e28341. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0028341

Isaac I (1949) A comparative study of pathogenic isolates of Verticillium. Trans Br mycol Soc 32: 137–157.

Isaac I (1953) A further comparative study of pathogenic isolates of Verticillium: V. nubilum Pethybr. and V. tricorpus sp. nov. Trans Br mycol Soc 36: 180–195.

Kandel SL, Henry PM, Goldman PH, et al. (2022) Composition of the Microbiomes from Spinach Seeds Infested or Noninfested with Peronospora effusa or Verticillium dahliae. Phytobiomes Journal 6: 169-180. doi: 10.1094/PBIOMES-05-21-0034-R

Khambhati VH, Abbas HK, Sulyok M, et al. (2020) First Report of the Production of Mycotoxins and Other Secondary Metabolites by Macrophomina phaseolina (Tassi) Goid. Isolates from Soybeans (Glycine max L.) Symptomatic with Charcoal Rot Disease. Journal of Fungi 6(4): 332. doi: 10.3390/jof6040332

Kombrink A, Rovenich H, Shi-Kunne X, et al. (2017) Verticillium dahliae LysM effectors differentially contribute to virulence on plant hosts. Molecular Plant Pathology 18: 596–608. doi: 10.1111/mpp.12520

Liang Y, Cui S, Tang X, et al. (2018) An Asparagine-Rich Protein Nbnrp1 Modulate Verticillium dahliae Protein PevD1-Induced Cell Death and Disease Resistance in Nicotiana benthamiana. Front. Plant Sci. 9:303. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2018.00303

Ligoxigakis EK, Vakalounakis DJ (1994) The incidence and distribution of races of Verticillium dahliae in Crete. Plant Pathology 43: 755-758. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3059.1994.tb01616.x

Lima WN, de Sousa Santos Alves CP, Negreiros AMP, et al. (2024) Macrophomina pseudophaseolina isolated from weeds is pathogenic against cowpea, mung bean, corn, and sorghum. Eur J Plant Pathol 168: 225–230. doi: 10.1007/s10658-023-02748-2

, , , et al (2021) Verticillium dahliae secreted protein Vd424Y is required for full virulence, targets the nucleus of plant cells, and induces cell death. Molecular Plant Pathology 00, 1– 12. doi: 10.1111/mpp.13100

Liu T, Qin J, Cao Y, et al. (2022) Transcription Factor VdCf2 Regulates Growth, Pathogenicity, and the Expression of a Putative Secondary Metabolism Gene Cluster in Verticillium dahliae. Appl Environ Microbiol.: e0138522. doi: 10.1128/aem.01385-22

, , , et al. (2023) The glycoside hydrolase 28 member VdEPG1 is a virulence factor of Verticillium dahliae and interacts with the jasmonic acid pathway-related gene GhOPR9. Molecular Plant Pathology 24: 1238–1255. doi: 10.1111/mpp.13366

Mahato SB, Siddiqui KAI, Bhattacharya G, et al. (1987) Structure and stereochemistry of phaseolinic acid: A new acid from Macrophomina phaseolina. J. Nat. Prod. 50: 245–247. doi: 10.1021/np50050a024

Martín-Sanz A, Rueda S, García-Carneros AB, et al. (2018) Genetics, host range, and molecular and pathogenic characterization of Verticillium dahliae from sunflower reveal two differentiated groups in Europe. Front. Plant Sci. 9: 288. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2018.00288

Pegg GF, Brady BL (2002) Verticillium Wilts. Wallingford: CAB International. doi: 10.1079/9780851995298.0000

Radi S, Gulya T (2007) Sources of Resistance to a New Strain of Verticillium dahliae on Sunflower in North America-2006. Proceedings / Sunflower research workshop 2007 no.29. Link

Rafiei V, Banihashemi Z, Jiménez-Díaz RM, et al. (2018) Comparison of genotyping by sequencing and microsatellite markers for unravelling population structure in the clonal fungus Verticillium dahliae. Plant Pathology 67: 76–86. doi: 10.1111/ppa.12713

Ramezani M, Shier WT, Abbas HK, et al. (2007) Soybean Charcoal Rot Disease Fungus Macrophomina phaseolina in Mississippi Produces the Phytotoxin (−)-Botryodiplodin but No Detectable Phaseolinone. Journal of Natural Products 70(1): 128-129. doi: 10.1021/np060480t

Santhanam P, Boshoven JC, Salas O, et al. (2017) Rhamnose synthase activity is required for pathogenicity of the vascular wilt fungus Verticillium dahliae. Molecular Plant Pathology 18: 347–362. doi: 10.1111/mpp.12401

Seidl MF, Faino L, Shi-Kunne X, van den Berg GC, Bolton MD, Thomma BP (2015) The Genome of the Saprophytic Fungus Verticillium tricorpus Reveals a Complex Effector Repertoire Resembling That of Its Pathogenic Relatives. Molecular Plant-Microbe Interactions 28(3): 362-373. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-06-14-0173-R

Shi-Kunne X, Jové RP, Depotter JRL, et al. (2019) In silico prediction and characterisation of secondary metabolite clusters in the plant pathogenic fungus Verticillium dahliae. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 366(7): fnz081. doi: 10.1093/femsle/fnz081

Shier TW, Nelson J, Abbas HK, Baird RE (2012) Root Toxicity of the Mycotoxin Botryodiplodin in Soybean Seedlings. Toxicon 60(2): 163. doi: 10.1016/j.toxicon.2012.04.134

Snelders NC, Boshoven JC, Song Y, et al. (2023) A highly polymorphic effector protein promotes fungal virulence through suppression of plant-associated Actinobacteria. New Phytol. 237(3): 944-958. doi: 10.1111/nph.18576

Strausbaugh CA, Eujayl IA, Martin FN (2016): Pathogenicity, vegetative compatibility and genetic diversity of Verticillium dahliae isolates from sugar beet. Canadian Journal of Plant Pathology (online). doi: 10.1080/07060661.2016.1260639

Suaste-Dzul A, Veloso JS, Reis A (2021) First report of Verticillium dahliae race 2 on scarlet eggplant in Brazil. J Plant Pathol 103: 667. doi: 10.1007/s42161-021-00754-z

, , , et al. (2022) Verticillium diseases of vegetable crops in Brazil: Host range, microsclerotia production, molecular haplotype network, and pathogen species determination. Plant Pathology 71: 1417– 1430. doi: 10.1111/ppa.13562

, , , (2022) Development of a robust, VdNEP gene-based molecular marker to differentiate between pathotypes of Verticillium dahliae. Plant Pathology 71: 1404–1416. doi: 10.1111/ppa.13559

, , , et al (2024) Overexpression of an NLP protein family member increases virulence of Verticillium dahliae. Plant Pathology 00: 1–12. doi: 10.1111/ppa.13870

Usami T, Itoh M, Amemiya Y (2009) Mating type gene MAT1-2-1 is common among Japanese isolates of Verticillium dahliae. Physiol Mol Plant Pathol. doi:10.1016/j.pmpp.2009.04.002

Usami T, Itoh M, Amemiya Y (2009) Asexual fungus Verticillium dahliae is potentially heterothallic. Journal of General Plant Pathology 75: 422–427. doi: 10.1007/s10327-009-0197-6

, , , , (2022) Scarcity of major resistance genes against Verticillium wilt caused by Verticillium dahliae. Plant Breeding: 1– 14. doi: 10.1111/pbr.13046

, , , et al (2024) The secreted feruloyl esterase of Verticillium dahliae modulates host immunity via degradation of GhDFR. Molecular Plant Pathology 25: e13431. doi: 10.1111/mpp.13431

Xiao L, Tang C, Klosterman SJ, Wang Y (2023) VdTps2 Modulates Plant Colonization and Symptom Development in Verticillium dahliae. Mol Plant Microbe Interact. 36(9): 572-583. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-03-23-0024-R

Zare R, Gams W, Starink-Willemse M, Summerbell RC (2007) Gibellulopsis, a suitable genus for Verticillium nigrescens, and Musicillium, a new genus for V. theobromae. Nova Hedwigia 85: 463–489. doi: 10.1127/0029-5035/2007/0085-0463

Zhang N, Castlebury LA, Miller AN, et al. (2006) An overview of the systematics of the Sordariomycetes based on a four-gene phylogeny. Mycologia 98: 1076–1087. LINK

Zhang L, Ni H, Du X, et al. (2017) The Verticillium-specific protein VdSCP7 localizes to the plant nucleus and modulates immunity to fungal infections. New Phytologist 215(1): 368-381. doi: 10.1111/nph.14537

Zhang Y, Zhang J, Gao J, et al. (2018) The Colonization Process of Sunflower by a Green Fluorescent Protein-Tagged Isolate of Verticillium dahliae and its Seed Transmission. Plant Disease 102(9): 1772–1778. doi: 10.1094/PDIS-01-18-0074-RE

Zhao YL, Zhou TT, Guo HS (2016) Hyphopodium-Specific VdNoxB/VdPls1-Dependent ROS-Ca2+ Signaling Is Required for Plant Infection by Verticillium dahliae. PLoS Pathogens 27;12(7): e1005793. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1005793

Zhou T-T, Zhao Y-L, Guo H-S (2017) Secretory proteins are delivered to the septin-organized penetration interface during root infection by Verticillium dahliae. PLoS Pathog13(3): e1006275. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1006275

, , , et al. (2021) CGTase, a novel antimicrobial protein from Bacillus cereus YUPP‐10, suppresses Verticillium dahliae and mediates plant defence responses. Molecular Plant Pathology 22: 130– 144. doi: 10.1111/mpp.13014

Zhu X, Soliman A, Islam MR, Adam LR and Daayf F (2017) Verticillium dahliae’s Isochorismatase Hydrolase Is a Virulence Factor That Contributes to Interference With Potato’s Salicylate and Jasmonate Defense Signaling. Frontiers in Plant Science 8: 399. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2017.00399